AAA INT – Chapter 2: Professional and ethical considerations

Key Points to Highlight in Chapter 2

Ethical Standards:

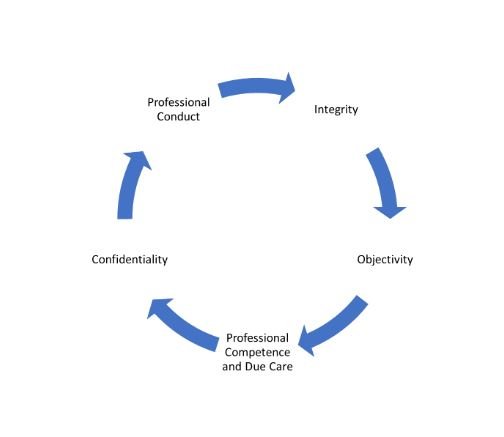

- Fundamental principles of IESBA: Integrity, objectivity, professional competence and due care, confidentiality, professional behavior.

- ACCA Code of Ethics: Addresses threats to fundamental principles like integrity and objectivity.

Threats to Independence:

- IESBA addresses threats like self-interest, advocacy, and familiarity.

- Not explicitly addressed: Performance threat.

Safeguards:

- Implemented to mitigate threats to ethics.

- Examples: Use of independent experts, rotation of senior personnel, quality control procedures.

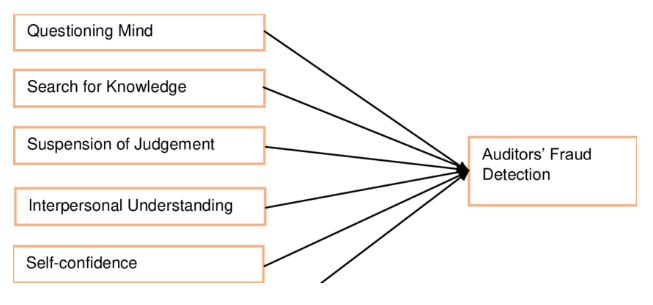

Professional Skepticism:

- Required by ISAs for auditors.

- Involves questioning management’s assertions and recognizing the possibility of material misstatement.

Confidentiality:

- ACCA Code of Ethics prohibits sharing client information except as required by law or permitted by the client.

- Breaches include using client data for personal research.

Conflict of Interest:

- Situations like financial interest in the client, job offers, personal relationships may constitute conflicts of interest.

- Providing non-audit services may raise independence concerns.

Objectivity:

- Threats include self-interest, intimidation, self-review.

- Advocacy threat involves promoting client interests.

Professional Competence and Due Care:

- Requires auditors to perform their duties with proper supervision and care.

- Updating knowledge and methodologies is essential.

Fraud Detection:

- Auditors responsible for identifying and assessing the risk of material misstatement due to fraud.

- Not responsible for guaranteeing absence of all fraud.

Elements of Professional Skepticism:

- Suspecting management dishonesty, challenging assertions, questioning evidence.

Compliance with Ethical Principles:

- Breaches include sharing client information without permission, lack of supervision, using outdated methodologies.

Safeguards for Ethical Compliance:

- Include ethical training, rotation of partners, independent review processes.

Responsibility of IESBA:

- Establishes ethical standards for professional accountants globally.

Independence Threats:

- Recognized threats: Self-interest, advocacy, familiarity.

- Not recognized: Procedural threat.

Responsibility for Fraud Detection:

- Auditors responsible for considering the risk of material misstatement due to fraud, not for preventing or prosecuting fraud.

Maintaining Professional Skepticism:

- Involves actively questioning and seeking evidence to support management assertions.

Managing Conflict of Interest:

- Providing services to competitors may raise independence concerns.

- Investments in client shares through mutual funds may not necessarily constitute a conflict of interest.

Effective Safeguards:

- Firm-wide ethical training, partner rotation, independent review processes.

- Reducing quality control procedures weakens safeguards.

Primary Responsibility for Fraud Detection:

- Auditors responsible for identifying and assessing the risk of material misstatement due to fraud.

Professional Skepticism in Practice:

- Approaching the audit with a questioning mindset and actively seeking corroborating evidence.

This comprehensive guide explores the ethical considerations crucial for professional accountants, particularly in the context of Advanced Audit and Assurance (AAA). It delves into three key topics: Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants, Fraud and Error, and Professional Liability. Each section will provide in-depth explanations, theoretical frameworks, and illustrative examples to solidify your understanding.

Topic 1: Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants

a) Fundamental Principles and the Conceptual Framework Approach

The International Ethics Standards Board (IESB) established the Code of Ethics for Professional Accountants, outlining five fundamental principles that underpin all professional conduct:

- Integrity: Professional accountants should be straightforward and honest in their professional relationships.

- Objectivity: Professional accountants should maintain professional judgment free from bias or undue influence.

- Professional Competence and Due Care: Professional accountants have a responsibility to maintain their professional knowledge and skill at a level required to ensure that client or employer interests are served competently.

- Confidentiality: Professional accountants must respect the confidentiality of information acquired in a professional relationship and refrain from disclosing it without proper authorization.

- Professional Conduct: Professional accountants should comply with relevant laws and regulations and avoid any action that discredits the profession.

The conceptual framework approach emphasizes the importance of considering all five principles interrelatedly when making ethical decisions. This ensures a holistic approach to ethical conduct, considering the specific context of each situation.

Illustration: An auditor is offered a significant financial incentive by a client to overlook a potential material misstatement in the financial statements. In this scenario, the fundamental principles of integrity and objectivity would be compromised. The auditor should decline the offer and uphold the ethical standards of the profession.

b) Identifying, Evaluating, and Responding to Threats to Compliance

Several threats can jeopardize compliance with the fundamental principles. These include:

- Self-interest threat: Occurs when a financial or other interest influences the auditor’s judgment. (e.g., an auditor owning significant shares in a client company)

- Self-review threat: Arises when the auditor is reviewing their own prior work or providing services that could compromise their independence.

- Advocacy threat: Compromises the auditor’s objectivity when they promote a client’s position over their professional judgment.

- Familiarity threat: Develops when a close relationship with a client hinders the auditor’s professional skepticism.

- Intimidation threat: Occurs when the auditor is pressured to compromise their professional judgment due to threats from the client.

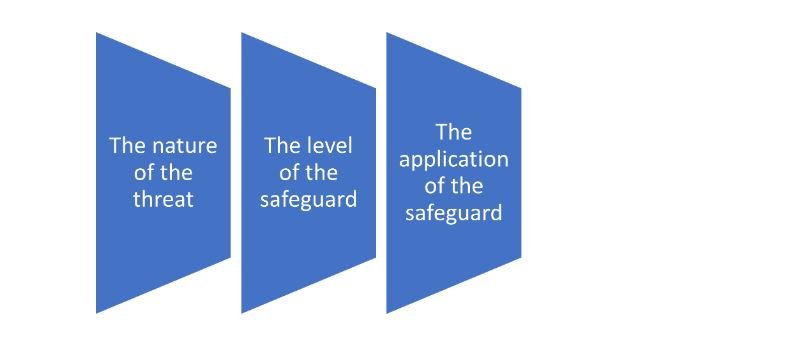

Evaluation: The severity of each threat is assessed based on its nature, level, and likelihood of occurrence.

Responding to Threats: Safeguards are implemented to mitigate threats. These may include:

- Safeguards: Procedures like partner rotation, second partner reviews, and cooling-off periods.

- Disclosure: Informing relevant parties about threats and safeguards.

Illustration: An audit firm is offered a lucrative consulting engagement by a client they are currently auditing. This poses a self-interest threat. The firm can mitigate this by establishing a separate team for the consulting engagement and ensuring no audit team members are involved.

c) Effectiveness of Available Safeguards

The effectiveness of safeguards depends on several factors:

- The nature of the threat: Some threats are more difficult to mitigate than others.

- The level of the safeguard: Stronger safeguards are more effective.

- The application of the safeguard: Consistent and proper application is crucial.

Evaluation: The adequacy of safeguards is continuously assessed throughout the engagement.

d) Recognizing and Advising on Conflicts

Conflicts can arise when applying the fundamental principles. For example, a situation might require maintaining confidentiality but also disclosing information to regulators.

Advising on Conflicts: In such scenarios, the professional accountant should:

- Identify the conflict and the relevant principles involved.

- Seek advice from superiors or ethics committees.

- Consider all available courses of action.

- Disclose the conflict to relevant parties when necessary.

Illustration: An auditor discovers that a client’s manager has been diverting company funds for personal gain. This creates a conflict between confidentiality towards the client and the obligation to report potential wrongdoing. The auditor should discuss this with their superiors and potentially disclose the information to the appropriate authorities.

e) Importance of Professional Skepticism

Professional skepticism is an essential attribute for auditors. It involves a questioning mind and a critical assessment of audit evidence throughout the engagement.

Why is it important? Professional skepticism helps auditors:

- Identify areas of increased risk of error or fraud.

- Evaluate the reliability of management representations.

- Design and perform appropriate audit procedures.

Maintaining Skepticism: Auditors can maintain skepticism by:

- Considering the possibility of management bias.

- Remaining alert to unusual or unexpected transactions.

- Corroborating audit evidence through independent sources.

- Challenging management assumptions when necessary.

Illustration: An auditor reviewing inventory records notices a significant increase in inventory levels compared to prior periods. Professional skepticism would require the auditor to investigate the reasons behind this increase and ensure the inventory is accurately valued.

f) Ethical Implications of Non-Audit Services

External auditors can provide various non-audit services to clients, such as tax consulting or internal audit. However, this raises ethical concerns related to:

- Independence: Providing non-audit services can create a self-interest threat, potentially compromising the auditor’s objectivity.

- Familiarity threat: Close relationships with clients developed through non-audit services can hinder the auditor’s professional skepticism.

Addressing Concerns:

- Safeguards: Implementing safeguards like partner rotation and cooling-off periods.

- Communication: Disclosing the nature of non-audit services to relevant parties.

Internal Audit Services: Providing internal audit services presents a more significant threat to independence. Generally, it’s discouraged for external auditors to offer these services to the same client they are auditing.

Illustration: An audit firm provides tax consulting services to a client they are also auditing. This creates a self-interest threat. The firm should ensure a separate team handles the tax services and that there is no communication between the tax and audit teams regarding audit-sensitive matters.

g) Assessing Engagement with Professional Skepticism

The audit approach and procedures should reflect an attitude of professional skepticism.

Evaluation: Consider whether:

- The audit plan addresses identified risks.

- Sufficient audit evidence has been obtained.

- Inconsistencies or red flags have been adequately investigated.

Implications: Inadequate professional skepticism can lead to:

- Audit failure: Missing material misstatements in the financial statements.

- Loss of public confidence: Erosion of trust in the audit profession.

Illustration: An auditor accepts management’s explanations for unusual transactions without performing sufficient corroborative procedures. This lack of skepticism could lead to missing a potential fraud scheme.

Topic 2: Fraud and Error

a) Identifying and Responding to High-Risk Circumstances

Several factors can indicate a heightened risk of error or fraud:

- Management pressure to meet financial targets.

- Weak internal controls.

- Changes in management or ownership.

- History of financial reporting irregularities.

- Complex or unusual transactions.

Responding to High Risk:

- Increased audit procedures: Performing more extensive testing, especially in high-risk areas.

- Brainstorming sessions: Audit team discussions to identify potential fraud risks.

- Use of computer-assisted audit techniques (CAATTs): Leveraging data analytics to detect anomalies.

Illustration: An auditor is aware that the client is facing significant financial pressure and has a history of aggressive accounting practices. This suggests a high risk of potential misstatements. The auditor should increase their testing procedures and consider using CAATTs to analyze financial data.

b) Responsibilities of Management and Auditors for Fraud and Error

Management:

- Preparation of fair and accurate financial statements: Management is primarily responsible for ensuring the accuracy of financial records.

- Implementation and maintenance of adequate internal controls: Internal controls help prevent and detect fraud and errors.

Auditors:

- Perform an audit in accordance with auditing standards: Auditors’ responsibility is to provide reasonable assurance, not absolute certainty, of the financial statements’ fairness.

- Identify and report material misstatements: Auditors should design and perform procedures to detect potential errors and fraud.

Illustration: Management is responsible for ensuring accurate inventory records. However, the auditor is responsible for designing and performing audit procedures to test the inventory valuation for reasonableness.

c) Investigating Misstatements

If an auditor suspects misstatements, they should:

- Gather additional evidence: Perform more extensive testing to confirm or refute the suspicions.

- Obtain management explanations: Seek clarification from management regarding the suspected misstatements.

- Consider the use of specialists: Engage forensic accountants or other specialists if necessary.

Illustration: An auditor identifies an unusually high number of fictitious invoices recorded in the client’s accounts payable system. The auditor should investigate further by obtaining supporting documentation for these invoices and potentially engaging a forensic accountant to assist with the investigation.

d) Reporting Fraud and Error

Reporting to Management: The auditor should communicate all identified or suspected misstatements to the appropriate level of management.

Reporting to Regulators or Third Parties: In certain situations, auditors may be obligated to report fraud or errors to regulators or third parties, such as when:

- The misstatement is material and has not been corrected by management.

- There is a threat to public safety.

- The auditor believes a crime has been committed.

Withdrawal from Engagement: Auditors may consider withdrawing from an engagement if:

- Management refuses to address material misstatements.

- The client interferes with the audit process.

- The auditor loses independence or professional skepticism.

Illustration: The auditor discovers a material fraud scheme and communicates it to management. However, management refuses to take corrective action. In this scenario, the auditor may be obligated to report the fraud to regulators and consider withdrawing from the engagement.

e) The Role of Auditors in Preventing, Detecting, and Reporting Error and Fraud

Current and Future Role:

- Focus on risk assessment: Auditors are increasingly focusing on identifying and assessing fraud risks throughout the engagement.

- Use of Technology: Data analytics and other technologies can enhance fraud detection capabilities.

- Communication and Collaboration: Stronger communication with management and collaboration with specialists can improve effectiveness.

Challenges:

- Management override of controls: Management can sometimes deliberately bypass internal controls.

- Collusion: Fraudulent schemes often involve collusion between employees.

Bridging the Expectation Gap

The “expectation gap” refers to the difference between public perception of auditor responsibility for fraud detection and the actual limitations of an audit.

Strategies to Bridge the Gap:

- Public education: Educating the public about the nature and limitations of an audit.

- Enhanced communication: Auditors clearly communicating the scope of their work and limitations in detecting fraud.

- Continuous improvement: The audit profession continuously evolving its methodologies and standards to address emerging fraud risks.

Illustration: The public might expect auditors to always catch fraud. However, auditors can only provide reasonable assurance, not absolute certainty. By educating the public and clearly communicating limitations, the expectation gap can be narrowed.

This comprehensive guide on professional and ethical considerations should equip you with a strong foundation for navigating the complexities of the AAA environment. Remember, ethical conduct and professional skepticism are paramount in upholding public trust in the audit profession.

Topic 3: Professional Liability

a) Recognizing Circumstances for Legal Liability

Professional accountants can face legal liability for their professional actions or omissions. Liability can arise when:

- Negligence: Failure to exercise the level of care and skill expected of a professional in similar circumstances.

- Breach of Contract: Failure to fulfill the terms of a professional engagement agreement.

- Misrepresentation: Providing misleading or inaccurate information.

Criteria for Recognizing Liability:

- Duty of Care: A duty of care exists between the professional accountant and the client (contractual) or a third party (established by law).

- Breach of Duty: The professional accountant failed to meet the required standard of care.

- Causation: The breach of duty caused the client or third party to suffer a loss.

- Damages: The client or third party suffered a quantifiable financial loss.

Illustration: An auditor negligently fails to detect a material error in the financial statements. This error leads to an investor making a bad investment decision, resulting in financial loss. The auditor could be held liable for negligence.

b) Auditor Negligence and Potential Liability

Several situations can lead to an auditor being found negligent:

- Failure to obtain sufficient audit evidence: Not performing enough testing procedures to support the audit opinion.

- Inadequate professional skepticism: Failing to critically assess audit evidence or management explanations.

- Improper audit judgment: Making unreasonable conclusions based on the audit evidence gathered.

- Non-compliance with auditing standards: Not following the established guidelines for conducting audits.

Potential Liability Outcomes:

- Financial compensation: The auditor may be required to compensate the client or third party for the losses incurred.

- Reputational damage: A finding of negligence can damage the auditor’s reputation and professional standing.

- Regulatory sanctions: Auditing bodies may impose disciplinary actions against the auditor.

Illustration: An auditor accepts management’s explanations for a complex transaction without performing sufficient verification procedures. This negligence leads to a material misstatement remaining undetected in the financial statements. The auditor could be liable for financial losses suffered by investors who relied on the misleading financial statements.

c) Client vs. Third-Party Liability

Liability to Clients: Arises from a contractual relationship between the auditor and the client. The duty of care is established by the terms of the engagement agreement.

Liability to Third Parties: More complex and arises when the auditor owes a duty of care to a third party who relies on the audited financial statements (e.g., investors, creditors). Establishing a duty of care to a third party requires specific legal conditions to be met.

Illustration: An auditor is liable to the client (the company being audited) for failing to detect a material fraud scheme. However, establishing liability to a third-party investor who relied on the misleading financial statements might be more challenging depending on the legal jurisdiction.

d) Limiting Liability

Practicability and Effectiveness:

Limiting liability through measures like disclaimers or engagement letters has limitations. Courts may still find the auditor liable if their negligence caused significant harm.

Alternative Strategies:

- Maintaining professional competence: Keeping up-to-date with auditing standards and best practices.

- Strong risk assessment: Identifying and addressing potential risks throughout the engagement.

- Effective audit methodology: Designing and performing appropriate audit procedures.

- Clear communication: Transparent communication with clients about the scope and limitations of the audit.

Illustration: While disclaimers might be included in the engagement letter, they may not always shield the auditor from liability for significant negligence. Focusing on professional competence, strong risk assessment, and clear communication are more effective strategies to mitigate liability risks.

e) Principal Causes of Audit Failure and the Expectation Gap

Causes of Audit Failure:

- Inadequate professional skepticism: Failure to critically assess audit evidence.

- Management pressure: Undue pressure from management to compromise the audit process.

- Audit team competence: Lack of necessary knowledge and experience within the audit team.

- Complexity of transactions: Difficulty in auditing complex financial instruments or business models.

Expectation Gap:

The expectation gap refers to the difference between public perception of auditor responsibility for fraud detection and the actual limitations of an audit. Several factors contribute to this gap:

- Limited scope of audit: Audits provide reasonable assurance, not absolute certainty.

- Management override of controls: Management can sometimes bypass internal controls.

- Collusion: Fraudulent schemes often involve collusion between employees.

Bridging the Gap:

Strategies discussed earlier (public education, enhanced communication, continuous improvement) remain relevant for narrowing the expectation gap.

Illustration: An audit team fails to detect a material fraud scheme due to inadequate professional skepticism. This contributes to an audit failure and widens the expectation gap. If the public believes auditors are infallible in fraud detection, such an outcome can erode trust in the profession.

Recommendations for Addressing Audit Failure and Expectation Gap

- Focus on Audit Quality: The audit profession must continuously strive to improve audit quality through robust methodologies, training, and peer reviews.

- Enhanced Regulation and Oversight: Regulatory bodies can play a role in strengthening oversight of the audit profession and enforcement of auditing standards.

- Technological Advancements: Leveraging data analytics and other technological tools can enhance audit efficiency and effectiveness.

- Emphasis on Professional Skepticism: Cultivating a culture of professional skepticism throughout the audit process is crucial.

By addressing these factors, the audit profession can work towards minimizing audit failures and narrowing the expectation gap, ultimately restoring public confidence in the integrity of financial reporting.

Conclusion

This comprehensive guide has explored the critical aspects of professional and ethical considerations in Audit and Assurance. A strong understanding of the Code of Ethics, the ability to identify and respond to fraud and error, and awareness of potential liability risks are essential for every professional accountant. Remember, ethical conduct and professional skepticism are the cornerstones of a successful and trusted audit practice.