Basic Nursing Skills

Basic Nursing Skills

Introduction

Vital signs are key indicators of a patient’s health and physiological status. They provide essential information regarding the body’s current state and potential deviations from normal functions. Accurate measurement and interpretation of vital signs are fundamental nursing skills that require both theoretical knowledge and clinical expertise. The four primary vital signs include temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure. Additionally, oxygen saturation and pain assessment are often considered vital signs in clinical settings.

Measurement Techniques

1. Temperature

Methods of Measurement: Temperature regulation is a crucial aspect of homeostasis, and various methods are used to measure it accurately. Each method has specific indications, normal ranges, and potential influencing factors.

a.Oral Temperature:

The most common method, oral temperature, is taken by placing the thermometer under the patient’s tongue in the sublingual pocket. This area is highly vascular and reflects core body temperature efficiently.

- Normal range: 36.5°C to 37.5°C (97.7°F to 99.5°F).

- Procedure: Ask the patient to close their mouth around the thermometer for about 3 to 5 minutes or until the thermometer indicates the reading.

- Considerations: Not suitable for patients who are unconscious, confused, or have recently consumed hot/cold foods or fluids.

b. Axillary Temperature:

This method involves placing the thermometer in the patient’s axilla (armpit). Axillary temperatures tend to be 0.5°C (0.9°F) lower than oral measurements.

- Normal range: 35.9°C to 37.0°C (96.6°F to 98.6°F).

- Procedure: Place the thermometer in the axilla with the arm held close to the body for 5 to 10 minutes.

- Considerations: This method is less accurate than oral or rectal methods, making it suitable for screening but less reliable for critical patients.

c. Rectal Temperature:

Rectal temperature measurements are often considered the most accurate because they closely reflect core body temperature.

- Normal range: 37.0°C to 38.1°C (98.6°F to 100.4°F).

- Procedure: Insert a lubricated thermometer 2.5 to 3.5 cm (1 to 1.5 inches) into the rectum, making sure not to force it. Hold the thermometer in place for the appropriate time.

- Considerations: Avoid in patients with rectal trauma, recent surgery, or specific cardiac conditions (e.g., recent myocardial infarction due to vagal stimulation).

d. Tympanic Temperature:

This method measures the temperature of the tympanic membrane (eardrum) using an infrared sensor. It is quick, non-invasive, and suitable for various patients, including children.

- Normal range: 36.8°C to 37.8°C (98.2°F to 100°F).

- Procedure: Gently pull the ear (up and back for adults; down and back for children under 3 years) to straighten the ear canal and place the thermometer in the ear canal.

- Considerations: Inaccurate readings may occur if the ear canal is obstructed by cerumen (earwax) or if the probe is not properly positioned.

Factors Affecting Temperature:

Several factors can influence body temperature, and nurses must be aware of these when interpreting results:

- Age: Infants and elderly people may have difficulty regulating body temperature. Newborns have immature thermoregulatory systems, and elderly people may have lower baseline temperatures.

- Exercise:

Physical activity increases metabolism, resulting in elevated body temperatures.

- Circadian Rhythms: Body temperature tends to be lower in the morning and higher in the late afternoon and evening.

- Hormonal Fluctuations: Women may experience variations in body temperature due to menstrual cycles or pregnancy.

- Environment: Exposure to extreme heat or cold can affect body temperature.

2. Pulse

The pulse reflects the heart’s ability to pump blood through the circulatory system and can be assessed at various points where arteries are close to the skin. Pulse assessment provides information on heart rate, rhythm, and quality.

Pulse Sites:

- Radial Pulse:

Located on the lateral aspect of the wrist, just below the thumb. This is the most commonly used site for measuring pulse in adults.

Procedure: Use the pads of your index and middle fingers to press gently on the radial artery. Count the beats for 30 seconds and multiply by 2 for regular rhythms or for a full 60 seconds if the rhythm is irregular.

- Carotid Pulse:

Located in the neck, just lateral to the trachea. This site is often used during emergencies or in situations where peripheral pulses may be weak or absent.

Procedure: Gently palpate one side of the carotid artery at a time to avoid compromising blood flow to the brain.

- Brachial Pulse:

Located on the inner aspect of the arm, between the biceps and triceps muscles, this site is often used in infants or when taking blood pressure.

Procedure: Palpate the brachial artery and follow the same steps as for radial pulse measurement.

Normal Pulse Ranges:

- Adults: 60-100 beats per minute (bpm).

- Children (1-10 years): 70-120 bpm.

- Infants (0-1 year): 100-160 bpm.

Assessment Techniques:

Rate: Count the number of beats per minute.

Rhythm: Determine if the rhythm is regular or irregular. An irregular rhythm may indicate an arrhythmia and should be further investigated.

Strength (Amplitude): Graded on a scale from 0 to 4, with 2+ being normal:

- 0: Absent, not palpable.

- 1+: Weak, thready.

- 2+: Normal, easily palpable.

- 3+: Full, increased.

- 4+: Bounding.

Factors Influencing Pulse:

- Age: Younger patients generally have higher pulse rates, while older adults may have lower resting heart rates.

- Exercise: Physical activity increases pulse rate temporarily.

- Fever: Elevated body temperature often leads to an increased pulse.

- Medications: Some drugs, such as beta-blockers, can lower the pulse rate, while stimulants can increase it.

- Autonomic Nervous System: Stress, anxiety, and pain can stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, leading to a higher pulse rate.

3. Respiration

Respiration refers to the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the atmosphere and the blood. The assessment of respiration involves observing the rate, rhythm, and depth of breaths.

Rate, Rhythm, and Depth:

Rate: The normal respiratory rate for adults is 12-20 breaths per minute, with variations depending on age, activity, and health status.

- Newborns: 30-60 breaths per minute.

- Children: 20-30 breaths per minute.

Rhythm: This refers to the regularity of breaths. Respirations should be evenly spaced, with consistent timing between breaths.

- Irregular breathing patterns may indicate conditions such as Cheyne-Stokes respiration or Kussmaul’s breathing, which are associated with specific diseases like heart failure and diabetic ketoacidosis.

Depth: The depth of respiration can be described as shallow, normal, or deep. Shallow respirations may be observed in patients with pain or respiratory distress, while deep breathing can indicate compensation for metabolic acidosis.

Factors Influencing Respiratory Patterns:

- Age: Respiratory rate decreases as individuals grow older.

- Physical Activity: Exercise increases both the rate and depth of respiration to meet increased oxygen demands.

- Fever: Elevated body temperature can increase the respiratory rate.

- Medications: Sedatives and narcotics may depress respiration, while stimulants can increase it.

- Disease: Respiratory conditions such as asthma, COPD, or pneumonia can alter both the rate and pattern of breathing.

4. Blood Pressure

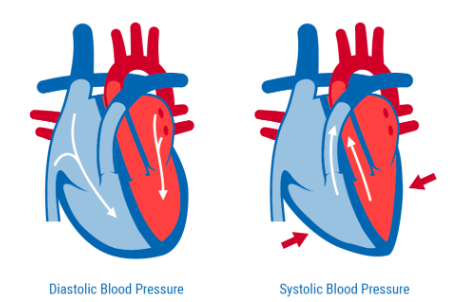

Blood pressure (BP) is the force exerted by circulating blood against the walls of the arteries. It is a critical measure of cardiovascular health and involves two components:

- Systolic pressure: The pressure exerted when the heart contracts and pushes blood into the arteries.

- Diastolic pressure: The pressure in the arteries when the heart rests between beats.

Measurement Techniques:

Manual Measurement (Auscultation): Blood pressure is traditionally measured using a sphygmomanometer and stethoscope.

- Procedure: The cuff is wrapped around the upper arm and inflated to a pressure that occludes the brachial artery. As the cuff is slowly deflated, the nurse listens with a stethoscope placed over the artery for the Korotkoff sounds that represent systolic and diastolic pressures.

Automatic Measurement: Electronic BP machines provide a quick and efficient method of measuring blood pressure, often used in clinical settings.

- Procedure: The cuff is placed around the patient’s arm and inflated automatically. The machine then deflates the cuff and digitally displays the systolic and diastolic pressures.

Normal Ranges:

- Adults: 90/60 mmHg to 120/80 mmHg.

- Prehypertension: 120-139/80-89 mmHg.

- Hypertension (Stage 1): 140-159/90-99 mmHg.

- Hypertension (Stage 2): ≥160/≥100 mmHg.

Factors Influencing Blood Pressure:

- Age: BP tends to rise with age due to increased arterial stiffness.

- Activity: Physical activity temporarily raises BP, while rest lowers it.

- Stress: Anxiety and stress stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, which raises BP.

- Medications: Antihypertensives lower BP, while certain stimulants can increase it.

- Positioning: BP can vary depending on body position (lying, sitting, standing).

Documentation and Interpretation

1. Accurate Documentation of Vital Signs:

The accurate recording of vital signs is crucial for monitoring changes in a patient’s condition over time. It includes:

- Time of measurement: Always document when the vital signs were taken to ensure correct monitoring.

- Measurement technique: Note the method used, especially for temperature and BP.

- Units: Ensure that vital signs are documented with appropriate units (e.g., °C for temperature, mmHg for blood pressure).

- Comments on abnormalities: If any vital sign is abnormal, document relevant observations (e.g., patient distress, skin color changes, complaints of dizziness).

2. Interpretation of Vital Signs:

Interpreting vital signs requires knowledge of normal ranges and the potential clinical implications of abnormalities:

- Temperature: Elevated temperatures (fever) may indicate infection, inflammation, or heatstroke. Low temperatures (hypothermia) may suggest exposure to cold, metabolic conditions, or shock.

- Pulse: Tachycardia (increased pulse rate) may be associated with pain, fever, dehydration, or anxiety. Bradycardia (decreased pulse rate) may occur in athletes, patients on beta-blockers, or those with heart conduction issues.

- Respiration: Tachypnea (increased respiratory rate) could indicate fever, anxiety, or respiratory disorders. Bradypnea (decreased respiratory rate) may result from drug overdose, head injuries, or hypothyroidism.

- Blood Pressure: Hypertension can lead to complications such as heart failure, kidney damage, or stroke, while hypotension may indicate shock, dehydration, or blood loss.

Conclusion

Vital signs provide critical information about a patient’s health, and their accurate measurement, documentation, and interpretation are core skills for nurses. By understanding the normal ranges, measurement techniques, and factors influencing these signs, nurses can detect early signs of deterioration and intervene appropriately to improve patient outcomes.

Basic Nursing Skills – Hygiene

Hygiene is a fundamental aspect of nursing care, essential for maintaining the health, comfort, and dignity of patients. This chapter covers various aspects of personal hygiene, infection control, and related nursing interventions to promote well-being and prevent the spread of infections. The provision of hygiene care is a core nursing responsibility and is integral to holistic patient care.

i. Personal Hygiene

Personal hygiene refers to the practices and procedures used to care for and maintain cleanliness of the body. It is essential for comfort, safety, and well-being. Nurses are responsible for helping patients with activities of daily living (ADLs) such as bathing, oral care, grooming, and ensuring that the patient maintains their hygiene to prevent infection and promote comfort.

Bathing

Bathing is one of the primary ways nurses assist in maintaining a patient’s personal hygiene. It removes dead skin cells, excess oils, dirt, and perspiration, reducing the risk of infections and promoting comfort. Bathing also stimulates circulation and provides the opportunity for nurses to perform skin assessments.

Types of Baths

- Complete Bed Bath:

This is typically for patients who are bedridden or unable to bathe themselves. Nurses perform the entire bathing process.

- Partial Bath:

In this method, the patient bathes parts of their body that are most prone to discomfort or infection, such as the face, hands, axillae (armpits), back, and perineal area. Nurses assist in areas the patient cannot reach.

- Sponge Bath:

A sponge bath is given to patients who cannot bathe in a tub or shower. Nurses use a basin of water and a sponge or washcloth to clean the body.

- Tub Bath/Shower: For patients who can leave the bed, tub baths or showers provide a more thorough cleansing. Nurses supervise or assist as needed, ensuring safety and preventing falls.

- Therapeutic Bath:

Often prescribed for patients with skin conditions, these baths can include medicinal substances to soothe the skin.

Techniques for Providing a Bath

- Warmth: Ensure the room is warm and the water temperature is comfortable, typically between 110-115°F (43-46°C).

- Privacy: Respect the patient’s dignity by ensuring privacy with curtains or doors and by keeping the patient covered as much as possible during the bath.

- Safety: Keep the bed rails up when turning patients and never leave them unattended in the bathroom. Ensure that non-slip mats are used for showers.

- Procedure: Wash from the cleanest to the dirtiest areas, typically starting from the face and moving toward the feet, using a fresh washcloth and clean water as needed. Pat the skin dry to avoid irritation.

Special Considerations

- Perineal Care: For patients with incontinence or following childbirth, extra care should be given to cleaning the perineal area to prevent infections like urinary tract infections (UTIs).

- Skin Assessments: During the bath, nurses can assess the skin for abnormalities such as redness, sores, pressure ulcers, rashes, or infections.

- Patient Involvement: Whenever possible, encourage patients to participate in their own hygiene care to promote independence and self-esteem.

Oral Care

Oral hygiene is an important part of overall health, preventing dental complications, gum disease, and systemic infections. Poor oral care can lead to the growth of bacteria in the mouth, which may spread to the lungs and cause pneumonia, particularly in vulnerable patients such as those who are elderly or immunocompromised.

Techniques for Oral Hygiene

- Brushing and Flossing: Nurses should encourage or assist patients in brushing their teeth at least twice a day. Use a soft-bristle brush and fluoride toothpaste to avoid damaging the gums. Flossing should be done once a day to remove plaque between teeth.

- Denture Care: For patients with dentures, it’s essential to clean the dentures daily, removing them overnight to prevent fungal infections and allow the gums to rest.

- Mouth Moisturizers: For patients who experience dry mouth, often due to medications, mouth moisturizers or water-based saliva substitutes can be applied to keep the oral mucosa moist.

- Chlorhexidine Rinse: For patients at high risk of oral infections, such as those who are immunocompromised or ventilated, chlorhexidine mouthwash can be used to prevent infections.

Special Considerations

- Unconscious Patients: Oral care for unconscious patients involves using a padded tongue depressor to hold the mouth open, using suction to remove secretions, and carefully brushing the teeth and gums to avoid aspiration.

- Mucositis: Patients undergoing chemotherapy or radiation may develop painful oral mucositis. Gentle cleaning and rinsing with a saline solution or prescribed oral rinse can help manage symptoms.

- Halitosis: Addressing bad breath (halitosis) can help promote a patient’s self-esteem and social comfort. This may involve recommending better oral hygiene, increasing fluid intake, or investigating underlying causes such as sinus infections or digestive issues.

Grooming

Grooming is another essential component of personal hygiene, promoting comfort, dignity, and well-being. It includes the care of hair, nails, and skin, which helps maintain cleanliness and enhance a patient’s psychological and emotional state.

Hair Care

- Daily Brushing: Brushing the hair daily helps stimulate the scalp and distribute natural oils along the hair shaft, promoting healthy hair and scalp.

- Shampooing: Depending on the patient’s condition and preferences, shampooing may be done in the shower, over a sink, or in bed using a shampoo cap or dry shampoo.

- Styling: Assisting patients in styling their hair can improve their self-esteem, especially those who are long-term care patients.

Nail Care

- Trimming and Filing: Nails should be kept clean and trimmed to avoid injury or infection. For patients with diabetes or circulatory issues, nail care should be done with caution to prevent injury.

- Assessment: Nurses should assess the nails for signs of infection, discoloration, or poor circulation, especially in patients with diabetes.

Skin Care

- Moisturizing: Patients with dry or fragile skin benefit from daily moisturizing to prevent skin breakdown.

- Shaving: Shaving may be offered to male patients as part of grooming. Use an electric razor for patients on anticoagulants to avoid the risk of cuts.

2.Infection Control

Infection control involves the procedures and practices that nurses implement to prevent and control the spread of infections. Proper infection control practices protect both patients and healthcare workers from the transmission of harmful microorganisms.

Hand Hygiene

Hand hygiene is the single most effective way to prevent the spread of infections. Nurses must perform hand hygiene before and after patient care, after touching contaminated objects, after removing gloves, and after using the restroom.

Handwashing Techniques

i. Soap and Water:

Use soap and water when hands are visibly dirty, after contact with body fluids, or after caring for patients with certain infections like Clostridioides difficile. The procedure involves:

- Wetting hands with warm water.

- Applying soap and lathering for at least 20 seconds, covering all surfaces of the hands and fingers.

- Rinsing thoroughly under running water.

- Drying with a clean towel or paper towel.

ii. Hand Sanitizers:

Alcohol-based hand sanitizers are effective when hands are not visibly soiled. Apply enough sanitizer to cover all surfaces of the hands and rub together until dry.

Factors That Affect Hand Hygiene Compliance

- Workload: Heavy patient loads can cause lapses in hand hygiene compliance.

- Skin Conditions: Frequent handwashing can lead to dry skin or dermatitis, leading some healthcare workers to avoid washing.

- Access: Having hand sanitizers easily available near patient care areas increases compliance.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

PPE acts as a barrier to protect nurses and patients from infection. Proper use, selection, and disposal of PPE are critical in preventing cross-contamination.

Types of PPE

- Gloves: Worn when there is a risk of contact with blood, body fluids, mucous membranes, non-intact skin, or contaminated surfaces. Gloves should be changed between procedures and after touching contaminated objects.

- Gowns: Worn to protect clothing and skin from contamination, especially during procedures that may involve splashing or contact with blood and body fluids.

- Masks and Respirators: Masks are used to prevent the spread of respiratory infections. Surgical masks protect against large respiratory droplets, while respirators (N95 or higher) provide protection against airborne pathogens like tuberculosis or COVID-19.

- Goggles/Face Shields: Worn to protect the eyes and mucous membranes from splashes or sprays of blood and body fluids.

Proper Use of PPE

- Donning (Putting on PPE): The correct order is to put on a gown first, followed by a mask or respirator, goggles or face shield, and then gloves.

- Doffing (Removing PPE): The correct removal sequence is gloves first, followed by goggles or face shield, gown, and then mask, minimizing the risk of contamination.

- Disposal: Dispose of PPE in designated bins immediately after use, and perform hand hygiene afterward.

Clean and Sterile Techniques

Infection control requires the use of two primary techniques: medical asepsis (clean technique) and surgical asepsis (sterile technique).

Medical Asepsis (Clean Technique)

- Definition: Medical asepsis refers to practices that reduce the number and spread of pathogens.

- Examples: Hand hygiene, using gloves when necessary, cleaning equipment, and disinfecting surfaces are all part of clean technique.

- Application: Used during routine care like inserting a urinary catheter, giving injections, or cleaning wounds.

Surgical Asepsis (Sterile Technique)

- Definition: Surgical asepsis eliminates all microorganisms from an area or object, creating a sterile environment.

- Examples: Sterile technique is used during surgeries, invasive procedures such as catheter insertions, and dressing changes of large or deep wounds.

- Maintaining a Sterile Field: Once a sterile field is established, nurses must avoid contamination by keeping hands above the waist and avoiding contact with non-sterile objects.

Conclusion

Maintaining personal hygiene and adhering to infection control practices are essential components of nursing care. These basic nursing skills not only improve patient comfort and dignity but also play a critical role in preventing infections and promoting health in healthcare settings. Proper hand hygiene, effective use of PPE, and understanding the difference between clean and sterile techniques help nurses provide safe, high-quality care across various clinical environments.

Infection Control

Infection control is a critical aspect of nursing care, essential for preventing healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) and protecting both patients and healthcare workers. Effective infection control involves implementing strategies that reduce the spread of pathogens, including the proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE), adhering to standard and transmission-based precautions, and ensuring proper disinfection and sterilization of equipment.

This section will cover in-depth the principles and applications of infection control, focusing on standard precautions, transmission-based precautions, and procedures for disinfection and sterilization.

1. Standard Precautions

Standard precautions are a set of infection prevention practices used to protect healthcare workers and patients from the transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. These precautions are based on the assumption that all blood, body fluids, secretions, excretions (except sweat), non-intact skin, and mucous membranes may contain transmissible infectious agents. Therefore, standard precautions are applied to all patients, regardless of their diagnosis or infection status.

Principles of Standard Precautions

Standard precautions include the following key components:

- Hand Hygiene: The most critical practice in infection control. Healthcare workers must clean their hands before and after patient contact, after touching potentially contaminated surfaces, and before performing aseptic tasks.

- Use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Depending on the nature of patient interaction and the potential exposure to blood and body fluids, healthcare workers should wear appropriate PPE (e.g., gloves, gowns, masks, and eye protection).

- Respiratory Hygiene/Cough Etiquette: Patients, visitors, and healthcare workers should cover their mouths and noses with a tissue or their elbow when coughing or sneezing, and perform hand hygiene immediately afterward.

- Safe Injection Practices: Includes the use of sterile needles and syringes, proper disposal of sharps, and aseptic techniques to avoid contamination during injections.

- Safe Handling of Equipment and Linens: Medical equipment and linens that come into contact with a patient’s blood or body fluids must be handled carefully to prevent contamination of other surfaces or individuals.

- Environmental Cleaning: Routine cleaning and disinfection of surfaces and equipment are crucial to maintaining a safe environment for patients and healthcare workers.

Application of Standard Precautions in Daily Care

- Gloving: Nurses should wear gloves when there is a risk of contact with blood, body fluids, or contaminated items. Gloves should be removed after completing the task, followed by hand hygiene.

- Masking and Eye Protection: If there is a potential for splashes or sprays of blood or body fluids, healthcare workers should wear masks and goggles or face shields to protect the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, and mouth.

- Gowning: Gowns should be worn if patient care activities are likely to generate splashes or sprays of blood, body fluids, secretions, or excretions.

- Handling and Disposal of Sharps: Needles, scalpels, and other sharp instruments should be handled carefully to prevent injuries. Discard used sharps in designated puncture-proof containers.

- Patient Placement: Patients with known or suspected infection should be placed in single-patient rooms if possible, or with patients who have the same type of infection.

2. Transmission-Based Precautions

In addition to standard precautions, transmission-based precautions are implemented for patients known or suspected to be infected with highly transmissible or epidemiologically significant pathogens. These precautions are based on the mode of transmission: contact, droplet, or airborne. Each type of precaution requires specific infection control measures to prevent the spread of infectious agents.

a) Contact Precautions

Contact precautions are used to prevent the spread of infections that are transmitted through direct or indirect contact with an infected individual or contaminated surfaces and objects. These infections are typically caused by microorganisms like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Clostridioides difficile (C. diff), and certain strains of Escherichia coli (E. coli).

Key Components of Contact Precautions

- Gloves and Gown: Healthcare workers must wear gloves and gowns when entering a patient’s room and during any contact with the patient or their environment. These should be removed before leaving the room, and hand hygiene must be performed immediately.

- Patient Placement: Patients should be placed in a private room, or cohorted with others infected with the same pathogen if necessary.

- Dedicated Equipment: Use of patient-dedicated or disposable medical equipment is encouraged to prevent cross-contamination. If shared equipment is necessary, it must be thoroughly disinfected between patients.

- Environmental Cleaning: Enhanced cleaning protocols are essential in rooms of patients on contact precautions. High-touch surfaces like bed rails, doorknobs, and medical equipment should be frequently disinfected.

Common Infections Requiring Contact Precautions

- MRSA (Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus): A type of staph bacteria that is resistant to many antibiotics. It is spread through direct contact with infected wounds, hands, or contaminated surfaces.

- C. difficile: A spore-forming bacterium that causes severe diarrhea and inflammation of the colon. Transmission occurs through contact with contaminated surfaces or feces.

- VRE (Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci): Bacteria that are resistant to the antibiotic vancomycin, spread through direct contact with wounds or contaminated surfaces.

b) Droplet Precautions

Droplet precautions are implemented for infections transmitted by large respiratory droplets (greater than 5 microns in size) that are generated when an infected person coughs, sneezes, talks, or undergoes procedures such as suctioning. These droplets can travel short distances (up to 3 feet) and can infect individuals through mucosal surfaces such as the nose, mouth, or eyes.

Key Components of Droplet Precautions

- Masks: Healthcare workers must wear surgical masks when within 3 feet of a patient with a droplet-transmitted infection.

- Patient Placement: Ideally, patients should be placed in a private room. If necessary, patients with the same infection can be cohorted. Patients should wear a mask if they need to be transported outside their room.

- Eye Protection: In some cases, eye protection may be necessary if splashes or sprays of respiratory secretions are anticipated.

Common Infections Requiring Droplet Precautions

- Influenza: A viral infection that affects the respiratory tract and is spread through droplets.

- Pertussis (Whooping Cough): A bacterial infection caused by Bordetella pertussis, spread via respiratory droplets.

- Meningitis (Neisseria meningitidis): A serious bacterial infection of the lining around the brain and spinal cord, transmitted through droplets.

c. Airborne Precautions

Airborne precautions are necessary for infections that are transmitted through small droplets or aerosolized particles (less than 5 microns in size) that can remain suspended in the air for extended periods and travel long distances. These particles can be inhaled by others, making airborne pathogens particularly dangerous.

Key Components of Airborne Precautions

- Respirators (N95 or higher): Healthcare workers must wear a fit-tested N95 respirator or higher-level respirator when caring for patients with airborne-transmitted infections.

- Negative Pressure Rooms: Patients should be placed in airborne infection isolation rooms (AIIRs) with negative pressure to prevent the spread of infectious particles to other areas of the healthcare facility. Air is filtered through high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters before being exhausted outside.

- Limiting Transport: Patients should remain in their rooms as much as possible. If transport is necessary, the patient must wear a surgical mask to prevent the spread of infectious particles.

Common Infections Requiring Airborne Precautions

- Tuberculosis (TB): Caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, TB is primarily spread through airborne particles that are released when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

- Measles (Rubeola): A highly contagious viral infection transmitted through airborne particles. It can remain in the air for hours after the infected person has left the room.

- Varicella (Chickenpox): Caused by the varicella-zoster virus, this infection is transmitted via airborne particles and through direct contact with fluid from vesicles.

3. Disinfection and Sterilization

The final component of infection control is the proper cleaning, disinfection, and sterilization of equipment and the environment. These procedures help eliminate or reduce microorganisms on surfaces and instruments, preventing the transmission of infections in healthcare settings.

i. Cleaning

Cleaning is the process of removing dirt, organic material, and visible contaminants from surfaces or objects. It is the first and most crucial step before disinfection and sterilization, as organic matter can interfere with these processes. Cleaning involves using water, detergent, and mechanical action to scrub away debris.

- Manual Cleaning:

Scrubbing surfaces or instruments by hand to remove visible debris.

- Ultrasonic Cleaning:

Uses high-frequency sound waves to create cavitation bubbles that dislodge contaminants from surfaces, commonly used for delicate instruments.

ii. Disinfection

Disinfection refers to the process of eliminating most, but not all, microorganisms (excluding bacterial spores) from surfaces or objects. Disinfection can be classified into high, intermediate, and low levels, depending on the efficacy of the disinfectant and the level of microbial kill required.

Types of Disinfectants

- High-Level Disinfection (HLD): Eliminates all microorganisms except high levels of bacterial spores. Used for semi-critical instruments like endoscopes and respiratory therapy equipment. Common high-level disinfectants include glutaraldehyde and peracetic acid.

- Intermediate-Level Disinfection: Destroys mycobacteria, most viruses, and bacteria. It is used for non-critical instruments that come into contact with intact skin, such as blood pressure cuffs. Examples include alcohols and phenolic compounds.

- Low-Level Disinfection: Destroys some bacteria and viruses, but not spores or mycobacteria. Used for surfaces like floors and countertops.

Disinfection Protocols

- Non-Critical Equipment: Non-critical items such as blood pressure cuffs and stethoscopes should be disinfected between patients using low- or intermediate-level disinfectants.

- Environmental Surfaces: Frequently touched surfaces such as bed rails, door handles, and light switches should be cleaned and disinfected regularly to prevent cross-contamination.

iii. Sterilization

Sterilization is the process of eliminating all forms of microbial life, including bacterial spores. This is essential for critical instruments that enter sterile body tissues or the vascular system, such as surgical instruments, catheters, and implants.

Methods of Sterilization

- Steam Sterilization (Autoclaving): Uses high-pressure steam to kill all microorganisms and spores. It is the most common and effective method for sterilizing heat-resistant medical instruments.

- Ethylene Oxide (EtO) Gas: A chemical sterilant used for heat-sensitive instruments. It requires a long aeration time to remove the gas residue from the equipment.

- Hydrogen Peroxide Gas Plasma: A low-temperature sterilization process used for delicate instruments. It is faster than EtO and does not leave toxic residues.

- Dry Heat Sterilization: Uses high temperatures to kill microorganisms, typically used for items that might be damaged by moist heat (e.g., powders, oils).

Sterilization Monitoring

- Biological Indicators: Vials or strips containing bacterial spores are placed with instruments during sterilization to ensure that the process is effective. After sterilization, these indicators are incubated to check for spore growth.

- Chemical Indicators: Tapes, strips, or labels that change color when exposed to sterilization conditions, providing a quick visual check that the process has occurred.

Conclusion

Infection control is an integral part of nursing practice, involving both standard and transmission-based precautions. The proper application of these precautions, along with effective disinfection and sterilization methods, is crucial in preventing the spread of infections in healthcare settings. By adhering to these principles, nurses play a critical role in safeguarding the health and well-being of their patients and the broader healthcare environment.