Comprehensive Physical Assessment Techniques

Comprehensive Physical Assessment Techniques

A comprehensive physical assessment is a systematic, head-to-toe evaluation of a patient’s health status. It helps nurses gather detailed information about a patient’s physical, emotional, and psychological condition. This data is crucial for formulating accurate diagnoses, developing care plans, and tracking patient progress over time.

The four core assessment techniques utilized in a comprehensive physical assessment are inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. Each of these techniques provides specific information about different body systems, ensuring a thorough understanding of the patient’s overall health.

A. Assessment Techniques

Inspection

Inspection is the process of observing the body parts and systems visually. It begins as soon as the nurse enters the patient’s environment and continues throughout the assessment. This technique is non-invasive, and nurses use their eyes, ears, and nose to identify any deviations from normal. Inspection is often the first step in the assessment and can reveal much information about the patient’s health.

Visual Examination

Systematic Observation: During inspection, the nurse systematically observes the patient’s body from head to toe, looking for abnormalities such as asymmetry, discoloration, swelling, deformities, lesions, scars, rashes, or abnormal body movements.

- Color changes: Nurses assess for jaundice (yellowing of the skin or sclera), cyanosis (bluish tint to the skin, indicating hypoxia), pallor (paleness, which may indicate anemia), or erythema (redness that could suggest inflammation or infection).

- Edema: Swelling, particularly in the lower extremities, may indicate fluid retention due to heart failure, kidney disease, or other conditions.

- Deformities: The shape and structure of joints, bones, and muscles are examined for abnormalities, such as fractures, dislocations, or congenital deformities like scoliosis or clubfoot.

- Skin Integrity: The nurse observes for any breakdowns, pressure ulcers, or other abnormalities in the skin, which could indicate immobility or malnutrition.

Behavior and Emotional Condition: Observation of the patient’s affect, mood, and emotional state is also part of inspection. For example, an anxious or withdrawn patient may display different postures or facial expressions that give clues to their psychological health.

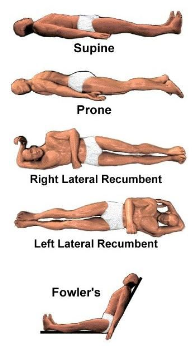

Patient Positioning

Proper patient positioning is essential during inspection to ensure that every body part can be fully visualized and inspected. Some common positions include:

- Supine Position: The patient lies flat on their back, which is useful for inspecting the anterior thorax, abdomen, and extremities.

- Prone Position: The patient lies on their stomach, allowing inspection of the back, buttocks, and posterior legs.

- Lateral Position: The patient lies on their side, which is often used for inspecting the posterior lungs and back.

- Sitting/ Fowler’s Position: The patient sits upright, which facilitates inspection of the head, neck, thorax, and arms.

Positioning the patient correctly allows the nurse to inspect areas that may be difficult to observe, such as the posterior body, and provides better access for other assessment techniques, like palpation or auscultation.

Palpation

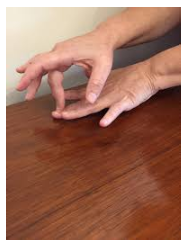

Palpation involves using the hands to touch and feel different parts of the body to assess texture, temperature, moisture, tenderness, and underlying structures. This technique can be divided into light and deep palpation, depending on the purpose and the depth of the structures being assessed.

Light Palpation

Technique: Light palpation is performed by gently pressing the fingertips (usually with the pads of the fingers) onto the skin, typically no deeper than 1 cm. This technique is used to assess surface characteristics such as skin texture, tenderness, temperature, and superficial masses.

- Skin Texture: The nurse feels for smoothness, roughness, or lesions. Rough or scaly skin may suggest conditions such as psoriasis or eczema, while excessively smooth or thin skin may indicate nutritional deficiencies or chronic steroid use.

- Tenderness: Tender areas may indicate inflammation, infection, or injury. The patient’s response to light palpation, such as wincing or pulling away, can help localize areas of pain.

- Temperature: Assessing skin temperature can provide clues about circulation and infection. Cold skin may indicate poor perfusion or shock, while warm skin can suggest infection or inflammation.

Deep Palpation

Technique: Deep palpation requires applying greater pressure, typically using both hands, one over the other. The nurse presses down to a depth of 4-5 cm to assess deeper structures, such as abdominal organs or muscle masses.

- Abdominal Organs: Deep palpation of the abdomen helps assess the liver, kidneys, spleen, and masses. For example, hepatomegaly (enlarged liver) or splenomegaly (enlarged spleen) can indicate underlying systemic diseases like liver cirrhosis or hematologic disorders.

- Muscle Masses: The nurse evaluates the size, consistency, and mobility of muscle masses or tumors. A fixed, hard mass may suggest malignancy, whereas a mobile, soft mass may be benign.

- Rebound Tenderness: During deep palpation, the nurse may assess for rebound tenderness, a sign of peritoneal inflammation, commonly seen in conditions like appendicitis.

Percussion

Percussion is a technique where the nurse taps on the body’s surface to produce sounds that provide clues about the underlying structures. This technique can help assess the size, density, and borders of organs, as well as the presence of fluid or air in body cavities.

Direct Percussion

Technique: In direct percussion, the nurse taps directly on the body surface with one or two fingers to assess for tenderness or pain in specific areas, such as the sinuses, chest, or abdomen.

- Sinuses: Direct percussion over the frontal and maxillary sinuses can help detect tenderness, which may indicate sinusitis or infection.

- Chest: Direct percussion on the chest can assess tenderness over the ribs, which may suggest a fracture or inflammation, such as in costochondritis.

Indirect Percussion

Technique: In indirect percussion, the nurse places one hand flat on the patient’s body and uses the fingers of the other hand to tap on the middle finger of the hand resting on the body surface. The sound produced varies depending on whether the underlying tissue is air-filled, fluid-filled, or solid.

- Lung Percussion: Percussion over the lungs produces different sounds depending on the amount of air or fluid present. Normal lung tissue produces a resonant sound, while areas of fluid or consolidation (such as in pneumonia) produce a dull sound.

- Abdominal Percussion: Percussion over the abdomen helps determine the presence of gas, fluid, or masses. A tympanic sound indicates air-filled structures (such as the stomach or intestines), while a dull sound suggests solid organs or masses.

Auscultation

Auscultation involves listening to internal sounds using a stethoscope to assess the function of organs like the heart, lungs, and bowels. This technique is crucial for identifying abnormal sounds, such as murmurs, wheezes, or absent bowel sounds, which may indicate underlying pathology.

Heart Sounds

Technique: The nurse listens to heart sounds by placing the stethoscope over the precordium (chest wall in front of the heart). The four main areas to auscultate are the aortic, pulmonic, tricuspid, and mitral areas.

- Normal Heart Sounds: The normal heart produces two primary sounds: S1 (“lub”) and S2 (“dub”). S1 is caused by the closure of the atrioventricular valves (mitral and tricuspid) at the beginning of systole, while S2 is produced by the closure of the semilunar valves (aortic and pulmonic) at the end of systole.

- Abnormal Heart Sounds: Murmurs are abnormal heart sounds caused by turbulent blood flow, often due to valve disorders, such as stenosis or regurgitation. Extra heart sounds like S3 and S4 may indicate heart failure or decreased ventricular compliance.

Lung Sounds

Technique: The nurse listens to the lungs by placing the stethoscope over the patient’s chest and back, comparing sounds bilaterally.

- Normal Breath Sounds: Normal breath sounds include vesicular sounds (soft and low-pitched, heard over most lung fields) and bronchial sounds (louder and higher-pitched, heard over the trachea).

- Abnormal Breath Sounds: Abnormal breath sounds include crackles (caused by fluid in the alveoli, often heard in pneumonia or heart failure), wheezes (whistling sounds due to narrowed airways, commonly heard in asthma or COPD), and rhonchi (low-pitched sounds caused by secretions in the airways).

Bowel Sounds

Technique: The nurse listens to bowel sounds by placing the stethoscope over the abdomen, usually starting in the right lower quadrant.

- Normal Bowel Sounds: Normal bowel sounds are gurgling noises caused by peristalsis, typically occurring every 5-30 seconds.

- Abnormal Bowel Sounds: Hypoactive bowel sounds may indicate decreased gastrointestinal motility, which can occur in conditions like paralytic ileus. Hyperactive bowel sounds suggest increased motility, seen in conditions such as gastroenteritis or early bowel obstruction. Absent bowel sounds, heard after five minutes of continuous listening, are an emergency and may indicate a bowel obstruction or perforation.

Conclusion

A comprehensive physical assessment that incorporates inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation provides nurses with vital data about a patient’s health. Mastery of these techniques is essential for identifying normal and abnormal findings, developing effective care plans, and promoting patient wellness. As each body system is unique, it requires a tailored approach to assessment, making these techniques a cornerstone of nursing practice.

Introduction to Systematic Approaches in Health Assessment

Nursing health assessments are essential in evaluating a patient’s overall health and identifying potential medical conditions. Nurses use systematic approaches to ensure a thorough, accurate, and consistent evaluation of the patient’s physical, emotional, and psychological states. There are two main types of systematic approaches to physical assessments:

- Head-to-Toe Assessment – A comprehensive, full-body assessment covering all major body systems.

- Focused Assessment – A targeted examination based on specific patient complaints or symptoms.

Both methods are integral to nursing practice, providing the necessary information to diagnose, plan, and implement patient care. A systematic approach ensures consistency, reduces the chances of missing critical information, and fosters a more organized and efficient assessment process.

A. Head-to-Toe Assessment

The head-to-toe assessment is a detailed and comprehensive examination that evaluates all body systems. It is typically performed on admission, during routine physical exams, or in situations where a full overview of the patient’s health is needed. This approach ensures that all areas are systematically assessed for abnormalities, providing baseline data for future comparisons.

Step-by-Step Head-to-Toe Assessment

The head-to-toe assessment is typically performed in a consistent order to avoid missing any areas of the body. Here is the breakdown:

1. General Survey and Mental Status Assessment

Before diving into each body system, the nurse performs a general survey and mental status evaluation. This is a critical first step, as it provides an initial impression of the patient’s overall health.

- Appearance: The nurse observes the patient’s general appearance, hygiene, posture, grooming, and clothing. Unkempt appearance may suggest neglect or mental health issues.

- Behavior: The nurse assesses the patient’s behavior, including eye contact, facial expressions, and cooperation. Agitation or unresponsiveness may signal distress, pain, or cognitive impairment.

- Level of Consciousness (LOC): The patient’s alertness and orientation to time, place, person, and situation are assessed. This is commonly done using the Glasgow Coma Scale to quantify consciousness levels.

- Speech: The nurse evaluates the patient’s speech for clarity, fluency, volume, and coherence. Slurred speech could indicate neurological impairment, while pressured speech may suggest anxiety or mania.

2. Head and Face

The head and face assessment begins at the top of the body and systematically progresses downward.

- Hair and Scalp: The nurse inspects for hair texture, distribution, and cleanliness. Conditions such as alopecia (hair loss) or seborrheic dermatitis (scalp scaling) can be observed.

- Skull and Scalp Palpation: The nurse palpates the skull to identify any deformities, lumps, or tenderness. Head trauma may cause palpable abnormalities such as hematomas.

- Facial Symmetry: The nurse checks for facial symmetry by having the patient smile, frown, and raise their eyebrows. Facial asymmetry may suggest Bell’s palsy or stroke.

- Skin: The skin is inspected for color, lesions, rashes, or signs of trauma. Palpation checks for skin temperature, texture, and turgor (elasticity), which provides clues about hydration status and underlying health conditions.

3. Eyes

Eye assessment includes both visual examination and functional tests to assess visual acuity and overall eye health.

- External Eye Structures: The nurse inspects the eyebrows, eyelashes, eyelids, conjunctiva, and sclera. Redness, swelling, or discharge may indicate infection or irritation. Scleral jaundice (yellowing of the whites of the eyes) is a key indicator of liver dysfunction.

- Pupils: Pupillary light reflex is assessed using the PERRLA (Pupils Equal, Round, Reactive to Light and Accommodation) method. Unequal pupils (anisocoria) may indicate neurological issues.

- Vision: Visual acuity is tested using the Snellen chart for distance vision and near-vision cards for reading. Any deficits may prompt further evaluation by an ophthalmologist.

4. Ears

The ear assessment involves inspection and palpation to evaluate external and internal ear health.

- External Ear: The nurse inspects the size, shape, and placement of the ears, looking for abnormalities such as swelling, discharge, or lesions. The external ear should be free from erythema and tenderness.

- Hearing Acuity: Hearing is assessed using the whisper test or tuning fork tests like the Rinne and Weber tests, which help differentiate between conductive and sensorineural hearing loss.

5. Nose and Sinuses

The nose and sinuses are inspected and palpated to assess airway patency and detect signs of infection or inflammation.

- Nasal Mucosa: The nurse inspects the nasal passages for color, swelling, discharge, or polyps. Pale or swollen mucosa may indicate allergic rhinitis, while purulent discharge suggests infection.

- Sinus Palpation: The frontal and maxillary sinuses are palpated for tenderness, which can signal sinusitis or an upper respiratory infection.

6. Mouth and Throat

The mouth and throat assessment involves the examination of oral structures, mucous membranes, and teeth.

- Lips and Oral Mucosa: The nurse inspects the lips, gums, tongue, and buccal mucosa for color, lesions, and moisture. Cyanosis (blue lips) indicates poor oxygenation, while dry mucous membranes may suggest dehydration.

- Teeth and Gums: The nurse examines the teeth for decay and the gums for signs of gingivitis (inflammation) or periodontal disease.

- Tonsils and Pharynx: The throat is examined for redness, swelling, or exudate, which may indicate tonsillitis or pharyngitis. The presence of pus or white patches on the tonsils may be indicative of bacterial infections like strep throat.

7. Neck

The neck assessment includes evaluation of the lymph nodes, thyroid, and carotid arteries.

- Lymph Nodes: The nurse palpates the cervical lymph nodes for size, consistency, and tenderness. Enlarged or tender lymph nodes may suggest infection or malignancy.

- Thyroid Gland: The nurse palpates the thyroid for enlargement or nodules. An enlarged thyroid (goiter) may indicate hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism.

- Carotid Arteries: The nurse auscultates the carotid arteries for bruits, which may indicate arterial narrowing or atherosclerosis.

8. Chest and Lungs

The chest and lung assessment includes inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation of the thorax to assess respiratory function.

- Chest Shape and Symmetry: The nurse observes the chest for any deformities, asymmetry, or abnormal breathing patterns, such as intercostal retractions or the use of accessory muscles. Conditions like pectus excavatum (sunken chest) or kyphosis can impact lung expansion.

- Breathing Pattern: Respiratory rate, rhythm, and effort are assessed. Rapid, shallow breathing may indicate respiratory distress, while irregular breathing may suggest neurological impairment.

- Lung Auscultation: The nurse listens to breath sounds, identifying normal vesicular breath sounds and abnormal sounds such as wheezes, crackles, or rhonchi. Crackles may indicate pulmonary edema or pneumonia, while wheezing is often heard in asthma or COPD.

9. Cardiovascular System

A thorough assessment of the cardiovascular system includes inspection, palpation, and auscultation of the heart and peripheral vessels.

- Heart Rate and Rhythm: The nurse assesses the apical pulse and listens for the regularity of the heart rate and rhythm. Any irregularities, such as arrhythmias, require further investigation.

- Heart Sounds: The nurse listens to the S1 and S2 heart sounds, as well as any extra sounds like S3 (indicating heart failure) or S4 (suggesting decreased ventricular compliance). Murmurs are assessed for their timing, location, and intensity, which can indicate valve disorders.

- Peripheral Circulation: The nurse assesses peripheral pulses (radial, brachial, dorsalis pedis, etc.) for strength and symmetry, as well as for any signs of edema or delayed capillary refill, which may indicate circulatory issues.

10. Abdomen

A detailed abdominal assessment involves inspection, auscultation, percussion, and palpation to evaluate the digestive organs.

- Abdominal Shape and Contour: The nurse inspects the abdomen for distension, bulging, or abnormal contour. A distended abdomen may indicate fluid buildup (ascites) or bowel obstruction.

- Bowel Sounds: The nurse auscultates the abdomen in all four quadrants, noting the frequency and character of bowel sounds. Hyperactive sounds suggest increased motility, while hypoactive or absent sounds may indicate a paralytic ileus or obstruction.

- Palpation: Light and deep palpation are performed to assess for tenderness, masses, or organ enlargement. Rebound tenderness may indicate peritoneal irritation, as seen in appendicitis.

11. Musculoskeletal System

The musculoskeletal system assessment evaluates the patient’s mobility, strength, and joint function.

- Range of Motion (ROM): The nurse assesses the patient’s ability to move joints through their full range of motion, noting any pain, stiffness, or limitation.

- Strength: The nurse assesses muscle strength in both upper and lower extremities, looking for any signs of weakness or asymmetry. Muscle atrophy may indicate disuse or underlying neuromuscular disorders.

- Posture and Gait: The nurse observes the patient’s posture and gait, assessing for any abnormalities such as limping, stiffness, or imbalance, which may indicate musculoskeletal or neurological impairments.

12. Neurological System

The neurological assessment involves evaluation of mental status, cranial nerves, motor function, sensory function, and reflexes.

- Mental Status: The nurse assesses cognitive function, orientation, memory, attention, and language.

- Cranial Nerve Function: Each of the 12 cranial nerves is tested to assess sensory and motor function, such as visual acuity (cranial nerve II) and facial symmetry (cranial nerve VII).

- Motor Function: Muscle strength, tone, and coordination are evaluated through various tests like handgrip strength and walking tests.

- Reflexes: Deep tendon reflexes (e.g., patellar, Achilles) are tested using a reflex hammer, with hyperactive or absent reflexes potentially indicating neurological dysfunction.

13. Skin, Hair, and Nails

The skin, hair, and nails assessment evaluates the integrity, color, and overall condition of these structures.

- Skin Color and Condition: The nurse observes skin for any changes in color (e.g., cyanosis, jaundice), lesions, or rashes. Skin turgor is also assessed to evaluate hydration status.

- Hair: Hair distribution, texture, and cleanliness are inspected, with any abnormalities possibly indicating underlying health conditions.

- Nails: The nails are inspected for color, shape, and signs of deformities (e.g., clubbing, which can indicate chronic hypoxia).

B. Focused Assessment

Unlike the head-to-toe assessment, the focused assessment is more targeted and specific to the patient’s presenting complaint or symptomatology. It zeroes in on the body system that is most affected and relevant to the patient’s current health status.

When to Perform a Focused Assessment

Focused assessments are often performed in situations where a patient presents with specific symptoms or has an existing medical condition that requires monitoring. For example:

- Patient with Chest Pain: A focused cardiovascular and respiratory assessment is performed to evaluate the cause of the chest pain. The nurse listens for heart murmurs, checks for irregular rhythms, and assesses breath sounds for abnormalities like crackles that may suggest heart failure.

- Patient with Shortness of Breath: The nurse performs a focused respiratory assessment, auscultating lung fields and evaluating respiratory effort. Percussion may reveal areas of dullness, indicating fluid accumulation, while auscultation may reveal wheezes or diminished breath sounds.

- Post-Surgical Patient: The nurse performs a focused abdominal assessment on a patient recovering from abdominal surgery. Bowel sounds are closely monitored, and palpation is used to assess for tenderness or distention that could signal postoperative complications.

Key Components of a Focused Assessment

- Chief Complaint: The nurse begins by asking the patient to describe their primary concern or symptom (e.g., pain, difficulty breathing, swelling), which directs the assessment.

- Targeted Examination: The nurse focuses on the body system most likely involved in the patient’s condition. For example, a patient presenting with joint pain would undergo a detailed musculoskeletal assessment.

- Symptom Characterization: The nurse explores the characteristics of the patient’s symptoms, including onset, location, duration, character, aggravating/relieving factors, and associated symptoms (e.g., using the OLDCART mnemonic: Onset, Location, Duration, Character, Aggravating/Relieving factors, Timing).

- Monitoring: Focused assessments often involve repeated checks to monitor changes in the patient’s condition. For example, a patient with pneumonia may have frequent respiratory assessments to track improvements or deterioration.

Examples of Focused Assessment by Body System

i. Cardiovascular Focused Assessment

For patients presenting with cardiovascular complaints, such as chest pain or palpitations, the nurse conducts a targeted examination that may include:

- Heart Rate and Rhythm: Assessing for arrhythmias.

- Blood Pressure: Measuring for hypertension or hypotension.

- Jugular Venous Distention (JVD): Indicating increased central venous pressure.

- Peripheral Edema: Suggestive of heart failure or poor circulation.

ii. Respiratory Focused Assessment

Patients with respiratory complaints, such as shortness of breath or wheezing, require a focused respiratory assessment:

- Breath Sounds: Checking for crackles, wheezes, or absent breath sounds.

- Oxygen Saturation: Monitoring SpO2 levels.

- Use of Accessory Muscles: Observing for labored breathing.

iii. Gastrointestinal Focused Assessment

For abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting, a focused gastrointestinal assessment is performed:

- Bowel Sounds: Assessing for hypoactive, hyperactive, or absent sounds.

- Palpation: Checking for tenderness, masses, or distention.

- Percussion: Identifying areas of dullness that may suggest fluid buildup.

Conclusion

A systematic approach to physical assessment, whether through a comprehensive head-to-toe assessment or a targeted focused assessment, allows nurses to identify potential health issues and gather critical data for diagnosis and care planning. The combination of inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation forms the foundation of these assessments. Nurses must remain methodical, organized, and observant to ensure no aspect of the patient’s health is overlooked. Mastery of these techniques ensures that patient care is thorough, efficient, and effective.

Comprehensive Physical Assessment Techniques: Documentation

1. Accurate Recording: Documenting Findings in a Clear and Organized Manner

Introduction to Documentation in Nursing

Documentation is a critical component of nursing practice. It serves as a legal record, facilitates communication among healthcare providers, and is crucial for the continuity of patient care. Proper documentation is key to ensuring that patient assessments, interventions, and outcomes are accurately recorded. Failure to properly document can lead to miscommunication, potential harm, and legal issues.

Importance of Accurate Recording

Accurate documentation serves multiple purposes in healthcare:

- Communication: Provides a means for healthcare professionals to share patient information and ensure continuity of care.

- Legal Record: Offers protection in case of lawsuits or disputes regarding patient care. Documentation is viewed as a legal document, and inaccuracies can lead to legal challenges.

- Billing and Reimbursement: Accurate documentation ensures proper coding and billing for services rendered. It plays a role in securing reimbursement from insurance companies and other third-party payers.

- Quality Assurance: Helps in tracking patient outcomes and measuring the quality of care provided. It also assists in identifying areas for improvement in practice.

- Research and Education: Documents can be used for clinical research, education, and quality improvement projects. It provides valuable insights into patient outcomes and care trends.

Key Principles of Accurate Documentation

- Objectivity: Documentation should be factual and free of subjective opinions. Avoid assumptions or interpretations of the patient’s condition unless supported by objective data.

- Timeliness: Record findings immediately or as soon as possible after the assessment to avoid omitting important details or introducing errors. Late entries should be clearly marked as such.

- Clarity: Use precise and clear language to describe findings. Avoid vague terms such as “appears” or “seems” unless they are clarified by supporting details.

- Brevity: Documentation should be concise but comprehensive. Unnecessary details or repetition can clutter records and make it difficult for other healthcare professionals to extract important information.

- Legibility: If using paper records, ensure handwriting is legible. Many healthcare systems now use electronic medical records (EMRs), which improve readability and organization.

- Patient Identification: Always ensure that the correct patient’s name, identification number, and other relevant details are included on every page of documentation.

Elements of Accurate Documentation

- Date and Time: Each entry must include the date and time it was made to create an accurate timeline of patient care.

- Patient Information: Ensure that all documentation includes the patient’s name, medical record number, and other identifying information.

- Assessment Findings: Document physical findings, vital signs, and results of diagnostic tests. Include subjective patient reports (such as pain) and objective findings (such as blood pressure readings).

- Interventions: Record all nursing interventions, including medications administered, treatments performed, and patient education.

- Evaluation of Interventions: Assess and document the patient’s response to interventions. For example, if pain medication is administered, note whether the pain was relieved.

- Plan of Care: Document ongoing plans for the patient’s care, including referrals, follow-up tests, or additional interventions.

- Patient Communication: Record any important conversations with the patient or family, including education provided, concerns raised, and the patient’s understanding of their condition or treatment plan.

Common Documentation Formats

Nurses use several formats to organize and document patient information. Each format serves a specific purpose depending on the setting or clinical scenario. Below are some common documentation methods:

- Narrative Notes: This traditional method involves writing a detailed, chronological account of patient care. While comprehensive, this format can be time-consuming and difficult to review.

- SOAP Notes: A structured format for documenting patient care, which is described in detail below.

- PIE (Problem, Intervention, Evaluation) Notes: A method that focuses on specific problems, the interventions taken, and the patient’s response.

- Focus Notes: These notes highlight a specific issue, such as a symptom or diagnosis, and document relevant information.

Legal and Ethical Considerations in Documentation

Accurate documentation is not only a matter of good practice but also a legal and ethical obligation for nurses. The following are critical legal and ethical aspects to keep in mind:

- Confidentiality: Adhere to HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) guidelines to protect patient privacy. Only authorized personnel should have access to patient records.

- Truthfulness: All documentation should be honest and accurate. Never alter or falsify records, as this is illegal and unethical.

- Informed Consent: Document any discussions about treatment options, risks, and the patient’s consent to proceed.

- Professional Accountability: Nurses are responsible for documenting the care they provide, including any errors or adverse events. Accurate documentation can help clarify the circumstances surrounding these incidents.

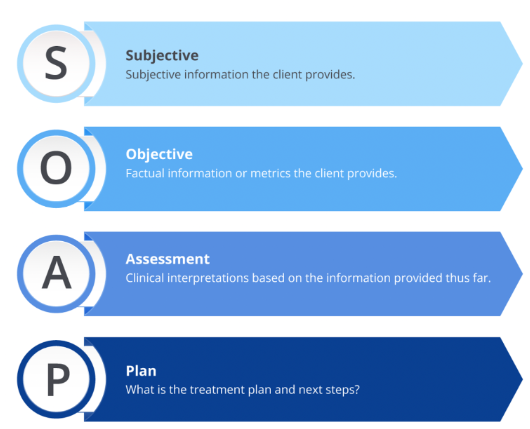

2. SOAP Notes: Using the Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan Format for Recording Assessment Data

Introduction to SOAP Notes

SOAP notes are a structured method for documenting patient encounters. This format helps healthcare professionals organize their findings and plan interventions in a clear, concise manner. SOAP notes stand for:

- Subjective: The patient’s personal account of their symptoms or concerns.

- Objective: Measurable data gathered during the assessment.

- Assessment: The nurse’s analysis of the situation based on subjective and objective data.

- Plan: The intended course of action to address the patient’s needs.

This standardized method is widely used in healthcare settings because it provides a logical flow from the patient’s complaint to the plan of care.

The Subjective Section

The subjective section includes information provided by the patient or their family members. This is often referred to as the patient’s “story,” and it helps to frame the context of the encounter. Subjective data includes:

- Chief Complaint (CC): A brief statement describing the primary reason for the patient’s visit, typically documented in the patient’s own words. Example: “I have chest pain.”

- History of Present Illness (HPI): A detailed description of the patient’s current symptoms, including onset, location, duration, character, aggravating/relieving factors, and timing. Nurses may use the OLDCART mnemonic to guide this assessment.

- Review of Systems (ROS): A review of other body systems to identify any additional symptoms. For example, a patient with chest pain might also report shortness of breath or nausea, which would be documented here.

- Past Medical History: Includes previous illnesses, surgeries, hospitalizations, allergies, and current medications.

- Family History: A review of the patient’s family medical history, which might reveal genetic predispositions to certain conditions.

- Social History: Information about the patient’s lifestyle, including tobacco, alcohol, and drug use, occupation, living situation, and social support.

Tips for Documenting Subjective Data

- Document the patient’s own words verbatim where possible, especially when describing the chief complaint. Use quotation marks to indicate the patient’s exact phrasing.

- If the patient is unable to provide information (e.g., due to altered mental status), document the source of the information (e.g., family member, medical record).

- Avoid interpreting or analyzing subjective data at this stage. Focus on recording what the patient reports.

Examples of Subjective Documentation

- CC: “My chest feels tight, and it started about 30 minutes ago.”

- HPI: “The patient describes the pain as sharp, located in the center of the chest, radiating to the left arm. The pain worsens with exertion and is relieved with rest.”

- ROS: “Denies fever, cough, or shortness of breath. Reports nausea and mild dizziness.”

The Objective Section

The objective section includes measurable data that the nurse gathers through physical examination, diagnostic tests, and observations. Objective data is factual and free from personal interpretation.

Key Elements of Objective Data

- Vital Signs: Record blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, and oxygen saturation.

- Physical Examination: Document findings from a head-to-toe physical examination, including inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. Note any abnormalities, such as rashes, tenderness, or abnormal lung sounds.

- Diagnostic Test Results: Include relevant laboratory or imaging results. For example, note the results of a chest X-ray or electrocardiogram (ECG).

- Observations: Document anything observed about the patient’s behavior, appearance, or environment. For example, a nurse might note that the patient appears anxious or diaphoretic (sweating).

Examples of Objective Documentation

- Vital Signs: BP 140/90, HR 88, RR 22, Temp 98.6°F, SpO2 95% on room air.

- Physical Exam: Chest auscultation reveals normal heart sounds without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. Breath sounds are clear bilaterally. Abdomen is soft, non-tender, with normoactive bowel sounds.

- Diagnostics: ECG shows sinus rhythm with no ST elevation. Chest X-ray pending.

The Importance of Accuracy in Objective Data

Accuracy in recording objective data is critical, as this section often serves as the foundation for diagnostic decision-making. Falsified or incorrect documentation can lead to misdiagnosis, incorrect treatment plans, and legal ramifications.

The Assessment Section

In the assessment section, the nurse synthesizes the subjective and objective data to develop a clinical impression or diagnosis. The assessment serves as an evaluation of the patient’s current health status based on the information gathered. It might involve:

- Differential Diagnosis: If the nurse is uncertain about the diagnosis, they may list potential diagnoses in order of likelihood.

- Clinical Judgment: Using critical thinking and clinical experience, the nurse assesses the severity of the patient’s condition.

- Identification of Problems: The nurse might identify nursing problems or needs, such as impaired gas exchange or risk for infection, and document them in this section.

Examples of Assessment Documentation

- Chest Pain: “The patient’s presentation is consistent with stable angina. Further workup, including cardiac enzymes and stress testing, is indicated.”

- Respiratory Distress: “The patient is experiencing mild respiratory distress, possibly secondary to asthma exacerbation. Will monitor SpO2 and administer bronchodilators as needed.”

The Plan Section

The final section of SOAP notes outlines the plan for managing the patient’s care. This might include further diagnostic tests, treatments, patient education, follow-up appointments, or referrals to specialists. The plan should be clear and actionable, with specific details about timing and follow-up.

Examples of Plan Documentation

- Chest Pain: “Plan to obtain cardiac enzymes and consult cardiology. Start nitroglycerin as needed for chest pain. Reassess in 1 hour.”

- Respiratory Distress: “Administer albuterol inhaler and recheck respiratory status in 30 minutes. Consider steroids if no improvement.”

Best Practices for Using SOAP Notes

- Ensure each section is complete. Leaving out any of the sections may result in incomplete documentation.

- Review and update the plan regularly based on changes in the patient’s condition.

- Always date and time SOAP notes, and include your signature or electronic initials to ensure accountability.

- Share SOAP notes with other healthcare providers to facilitate collaboration and ensure continuity of care.

Conclusion: Importance of Comprehensive and Structured Documentation

Effective documentation is essential in nursing to ensure continuity of care, legal protection, quality improvement, and accurate communication. Nurses must focus on accurate recording, particularly in structured formats like SOAP notes, to provide clear and organized documentation. Mastering these skills ensures the delivery of high-quality patient care and supports the professional standards required in nursing practice. By using formats such as SOAP notes, nurses can document data systematically, allowing other healthcare professionals to interpret patient information easily and accurately.