MSN: Gastrointestinal System

-

Anatomy and Physiology

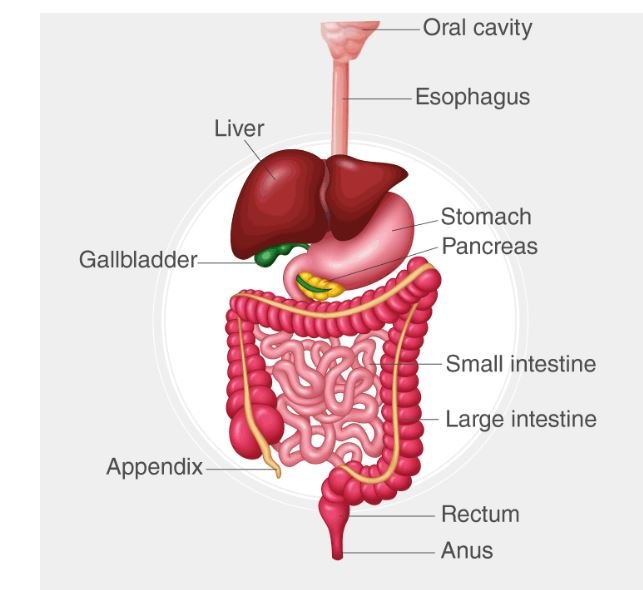

Digestive Organs and Their Functions

The gastrointestinal (GI) system is responsible for the ingestion, digestion, absorption, and elimination of food. It includes the following organs:

- Mouth: The entry point for food, where mechanical digestion begins through chewing (mastication) and chemical digestion starts with enzymes like amylase in saliva.

- Esophagus: A muscular tube that transports food from the mouth to the stomach through peristalsis.

- Stomach: A muscular organ that further breaks down food using gastric acid (HCl) and digestive enzymes, forming chyme. The stomach also plays a role in the absorption of certain substances, such as alcohol and aspirin.

- Small Intestine: Comprised of the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum, the small intestine is the primary site for digestion and absorption of nutrients. Enzymes from the pancreas and bile from the liver aid in the digestion of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates.

- Large Intestine: Includes the cecum, colon, and rectum. It absorbs water, electrolytes, and vitamins produced by gut bacteria, forming and storing feces for elimination.

- Liver: Produces bile, which is stored in the gallbladder and released into the small intestine to emulsify fats. The liver also metabolizes nutrients, detoxifies harmful substances, and stores vitamins and minerals.

- Pancreas: Exocrine functions include the secretion of digestive enzymes (e.g., lipase, amylase) into the small intestine. Endocrine functions involve the production of insulin and glucagon to regulate blood glucose levels.

- Gallbladder: Stores and concentrates bile produced by the liver, releasing it into the small intestine to aid in fat digestion.

Digestive Processes

Digestion involves both mechanical and chemical processes:

- Mechanical Digestion: Begins in the mouth with chewing and continues in the stomach with churning. This process breaks food into smaller pieces, increasing the surface area for enzymes to act upon.

- Chemical Digestion: Involves enzymes breaking down macromolecules into their building blocks (e.g., proteins into amino acids, carbohydrates into simple sugars, fats into fatty acids and glycerol). Key enzymes include amylase, lipase, and proteases.

- Absorption: Nutrients are absorbed primarily in the small intestine. The villi and microvilli in the intestinal lining increase the surface area for absorption. Water and electrolytes are absorbed in the large intestine.

Absorption and Metabolism

-

Absorption:

- Carbohydrates: Broken down into monosaccharides (e.g., glucose) and absorbed via active transport and facilitated diffusion in the small intestine.

- Proteins: Broken down into amino acids and absorbed through active transport in the small intestine.

- Fats: Emulsified by bile, broken down by lipase, and absorbed as fatty acids and monoglycerides into the lymphatic system via chylomicrons.

-

Metabolism:

- Carbohydrate Metabolism: Glucose is used for energy (via glycolysis and the citric acid cycle), stored as glycogen (glycogenesis), or converted into fat (lipogenesis).

- Protein Metabolism: Amino acids are used for protein synthesis, converted into glucose (gluconeogenesis), or oxidized for energy.

- Lipid Metabolism: Fatty acids undergo beta-oxidation to generate ATP, or they are stored as triglycerides in adipose tissue.

-

Assessment and Diagnosis

Abdominal Assessment

- Inspection: The abdomen is visually inspected for contour, symmetry, skin changes (e.g., jaundice, scars), distension, and visible peristalsis or pulsations.

- Palpation: Involves gently pressing on the abdomen to assess for tenderness, masses, and organ size. Light palpation detects surface abnormalities, while deep palpation assesses deeper structures.

- Percussion: Helps evaluate the size and density of abdominal organs. For example, the liver span can be assessed, and areas of tympany (gas) and dullness (fluid, feces) can be identified.

Bowel Sounds

- Auscultation: Involves listening to bowel sounds with a stethoscope. Normal bowel sounds are high-pitched and occur every 5-15 seconds. Hyperactive sounds may indicate gastroenteritis or obstruction, while hypoactive or absent sounds may suggest ileus or peritonitis.

Diagnostic Tests

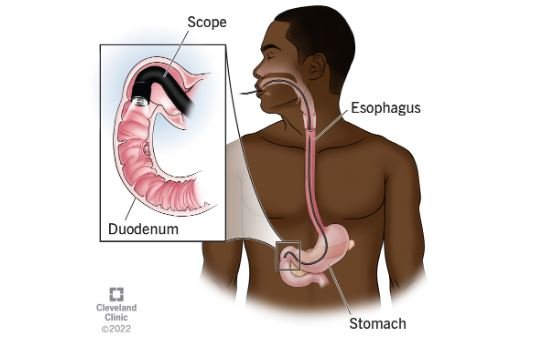

- Endoscopy:

- Upper Endoscopy (EGD):

Visualizes the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, useful in diagnosing ulcers, GERD, and tumors.

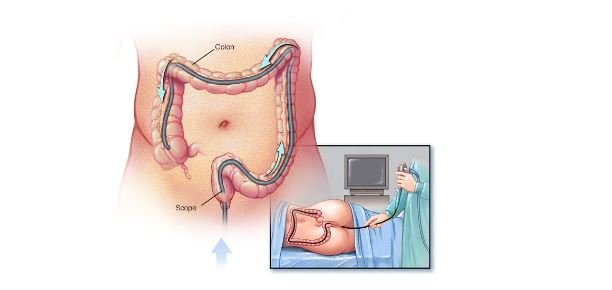

- Colonoscopy:

Examines the entire colon, detecting polyps, tumors, IBD, and sources of bleeding.

- Liver Function Tests (LFTs):

Measure enzymes (e.g., AST, ALT), bilirubin, and proteins to assess liver health. Elevated enzymes may indicate hepatitis, cirrhosis, or liver damage.

-

Common Gastrointestinal Conditions

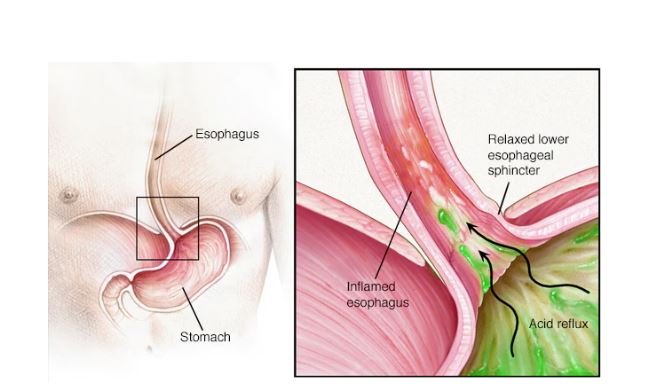

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

GERD is the chronic backflow of stomach contents into the esophagus, causing symptoms and potential complications:

- Pathophysiology: The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) fails to close properly, allowing acid to escape into the esophagus.

- Symptoms: Include heartburn, regurgitation, dysphagia, and chest pain. Chronic GERD can lead to esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma.

- Diagnosis: Based on symptoms, confirmed with endoscopy, pH monitoring, and esophageal manometry.

- Management: Includes lifestyle modifications (e.g., elevating the head of the bed, dietary changes), pharmacological therapy (e.g., proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers), and, in severe cases, surgical intervention (e.g., Nissen fundoplication).

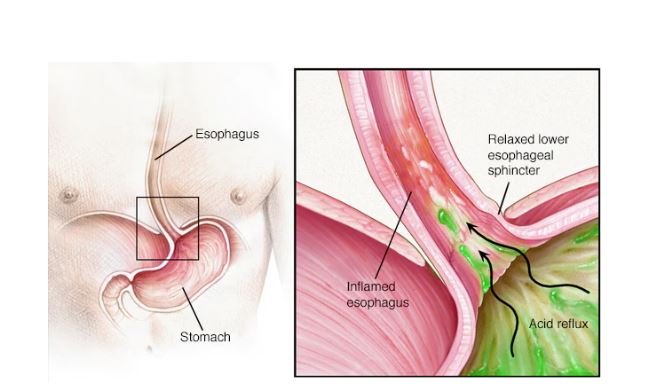

Peptic Ulcer Disease (PUD)

PUD involves the development of ulcers in the stomach or duodenum due to the erosion of the mucosal lining:

- Etiology: Most commonly caused by Helicobacter pylori infection and chronic use of NSAIDs. Other factors include smoking, alcohol use, and stress.

- Symptoms: Include epigastric pain (often relieved by eating in duodenal ulcers and worsened in gastric ulcers), bloating, and nausea.

- Diagnosis: Confirmed with endoscopy, biopsy (for H. pylori), and testing for H. pylori (urea breath test, stool antigen test).

- Management: Includes eradicating H. pylori with antibiotics, reducing gastric acid with PPIs or H2 blockers, and protecting the mucosa with agents like sucralfate. Surgery is reserved for complications like perforation or bleeding.

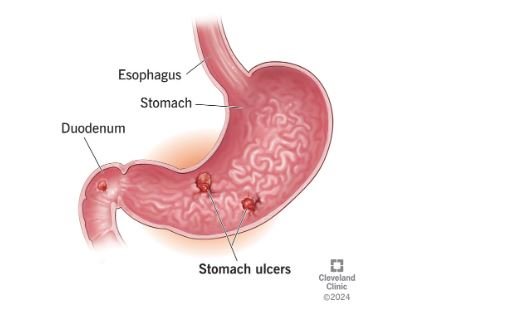

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

IBD encompasses chronic inflammatory conditions of the GI tract, primarily Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis:

- Crohn’s Disease: Can affect any part of the GI tract, often involving the ileum and colon, with transmural inflammation and skip lesions. Symptoms include diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, and fistulas.

- Ulcerative Colitis: Limited to the colon and rectum, characterized by continuous mucosal inflammation. Symptoms include bloody diarrhea, tenesmus, and abdominal cramping.

- Diagnosis: Includes colonoscopy with biopsy, imaging studies (e.g., CT, MRI), and serologic markers (e.g., pANCA, ASCA).

- Management: Involves anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., 5-ASA), immunosuppressants (e.g., azathioprine), biologics (e.g., infliximab), and, in severe cases, surgery (e.g., colectomy).

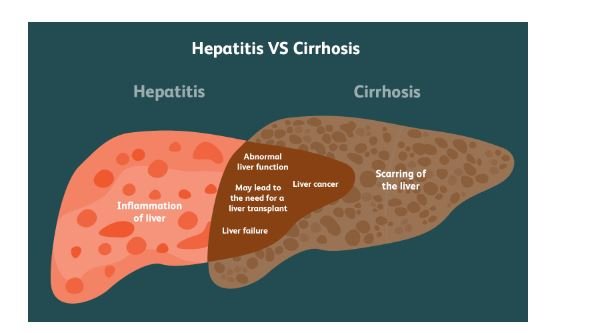

Hepatitis and Cirrhosis

- Hepatitis: Inflammation of the liver, often due to viral infections (Hepatitis A, B, C), alcohol, or toxins. Symptoms include jaundice, fatigue, anorexia, and hepatomegaly. Chronic hepatitis can progress to cirrhosis.

- Cirrhosis: The end-stage liver disease characterized by fibrosis, nodular regeneration, and loss of liver function. Complications include portal hypertension, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and variceal bleeding.

- Diagnosis: Liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing cirrhosis. Other tests include LFTs, ultrasound, elastography, and imaging studies.

- Management: Focuses on managing complications, abstaining from alcohol, treating the underlying cause (e.g., antivirals for hepatitis), and considering liver transplantation in advanced cases.

Gastrointestinal Bleeding

GI bleeding can occur anywhere in the GI tract and is classified as upper or lower GI bleeding:

- Upper GI Bleeding: Common causes include peptic ulcers, esophageal varices, and Mallory-Weiss tears. Symptoms include hematemesis (vomiting blood) and melena (black, tarry stools).

- Lower GI Bleeding: Common causes include diverticulosis, hemorrhoids, and colorectal cancer. Symptoms include hematochezia (bright red blood in stool).

- Diagnosis: Involves endoscopy (upper or lower), imaging studies, and lab tests (e.g., hemoglobin, hematocrit).

- Management: Includes stabilizing the patient (IV fluids, blood transfusions), endoscopic hemostasis (e.g., clipping, banding), and addressing the underlying cause.

-

Treatment and Management

Pharmacological Interventions

Antacids:

- Mechanism of Action: Neutralize stomach acid, providing symptomatic relief from heartburn and indigestion by increasing the pH of gastric contents.

- Examples:

- Calcium Carbonate (Tums): Provides rapid relief by neutralizing stomach acid; may cause constipation.

- Magnesium Hydroxide (Milk of Magnesia): Acts as an antacid and laxative; may cause diarrhea.

- Uses: Commonly used for symptomatic relief of GERD, dyspepsia, and peptic ulcers.

Antiemetics:

- Mechanism of Action: Reduce nausea and vomiting by acting on various receptors in the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract.

- Examples:

- Ondansetron (Zofran): A 5-HT3 receptor antagonist effective in preventing nausea and vomiting related to chemotherapy and surgery.

- Metoclopramide (Reglan): A dopamine antagonist that enhances gastric emptying and reduces nausea.

- Promethazine (Phenergan): An antihistamine with anticholinergic properties used to treat motion sickness and nausea.

- Uses: Indicated for nausea and vomiting from various causes, including postoperative, chemotherapy-induced, and motion sickness.

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs):

- Mechanism of Action: Inhibit the H+/K+ ATPase enzyme system in the gastric parietal cells, leading to a significant reduction in gastric acid secretion.

- Examples:

- Omeprazole (Prilosec): Used for GERD, peptic ulcers, and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

- Esomeprazole (Nexium): A more active isomer of omeprazole with similar indications.

- Uses: Effective for long-term management of GERD, peptic ulcer disease, and esophagitis.

H2 Receptor Antagonists:

- Mechanism of Action: Block histamine H2 receptors in the stomach lining, reducing gastric acid secretion.

- Examples:

- Ranitidine (Zantac): Reduces acid production and is used for GERD and peptic ulcers.

- Famotidine (Pepcid): More potent than ranitidine, used similarly for acid-related conditions.

- Uses: Suitable for short-term management of GERD, peptic ulcers, and dyspepsia.

Antibiotics:

- Mechanism of Action: Eradicate Helicobacter pylori infection, which is a common cause of peptic ulcers.

- Examples:

- Amoxicillin: A penicillin-type antibiotic effective against H. pylori.

- Clarithromycin: A macrolide antibiotic used in combination therapy.

- Metronidazole: Effective against anaerobic bacteria and protozoa, used in conjunction with other antibiotics.

- Uses: Part of a combination therapy to treat H. pylori infection in peptic ulcer disease.

Nutritional Support

Dietary Modifications:

-

For GERD:

Avoid foods and beverages that trigger symptoms, such as spicy foods, caffeine, chocolate, and alcohol. Eating smaller, more frequent meals can also help.

-

For IBD:

Depending on the phase of the disease, patients may need a low-residue diet during flare-ups to minimize bowel movements and discomfort. Nutritional supplements might be necessary for deficiencies.

-

For Hepatitis:

Focus on a balanced diet with adequate protein and calories while avoiding alcohol. In cases of cirrhosis, sodium restriction may be necessary to manage ascites.

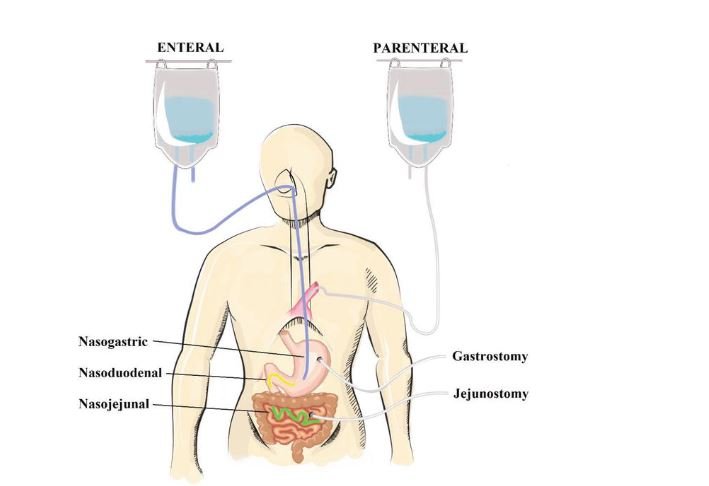

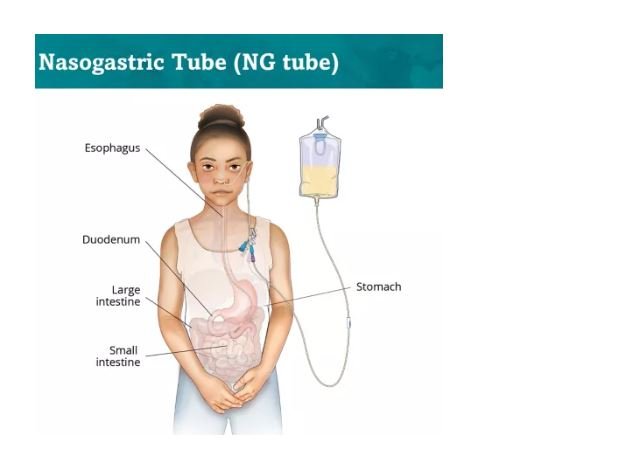

Enteral Nutrition:

- Definition: Provides nutrients via a feeding tube inserted into the GI tract. Used when oral intake is insufficient or impossible.

- Types:

- Nasogastric Tube (NG Tube): Short-term use for feeding directly into the stomach.

- Gastrostomy Tube (G Tube): Long-term use for direct access to the stomach.

- Indications: Includes conditions such as severe dysphagia, anorexia, or prolonged recovery from surgery.

Parenteral Nutrition:

- Definition: Provides nutrients intravenously when the GI tract is non-functional or inadequate for nutrient absorption.

- Types:

- Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN): Delivers all necessary nutrients, including glucose, amino acids, fats, vitamins, and minerals.

- Partial Parenteral Nutrition (PPN): Supplements oral or enteral nutrition when partial nutrient intake is insufficient.

- Indications: Used in cases of severe malabsorption, bowel obstruction, or short bowel syndrome.

Surgical Interventions

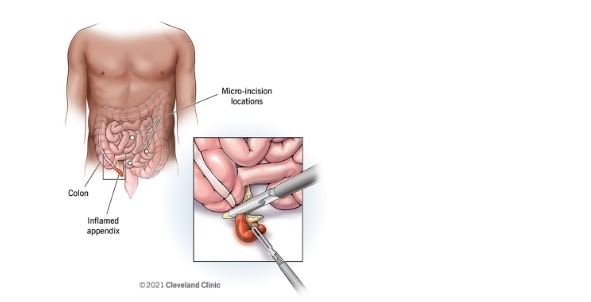

Appendectomy:

- Definition: Surgical removal of the appendix, typically performed for acute appendicitis.

- Types:

- Open Appendectomy: Traditional method with a larger incision.

- Laparoscopic Appendectomy: Minimally invasive with smaller incisions and quicker recovery.

- Indications: Appendicitis with or without complications such as perforation or abscess.

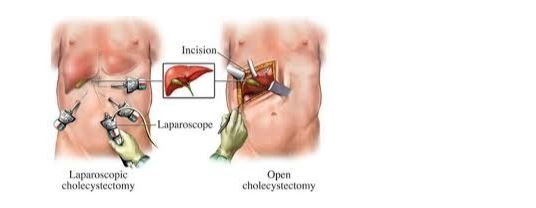

Cholecystectomy:

- Definition: Removal of the gallbladder, often due to symptomatic gallstones or cholecystitis.

- Types:

- Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Minimally invasive approach with quicker recovery and less postoperative pain.

- Open Cholecystectomy: Used in complicated cases or when laparoscopic methods are not feasible.

- Indications: Acute cholecystitis, chronic cholecystitis, and symptomatic gallstones.

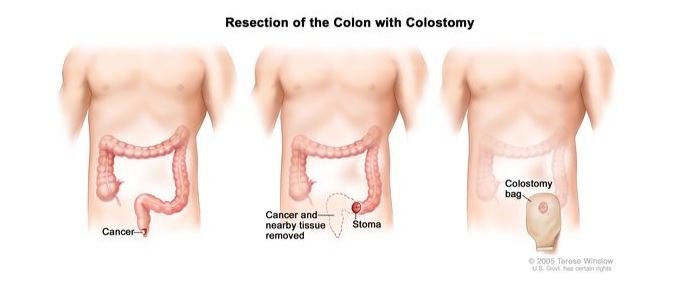

Resection:

- Definition: Surgical removal of a portion of the GI tract affected by disease.

- Types:

- Colectomy: Removal of part or all of the colon.

- Gastrectomy: Removal of part or all of the stomach.

- Indications: Conditions such as Crohn’s disease, colorectal cancer, or severe diverticulitis.

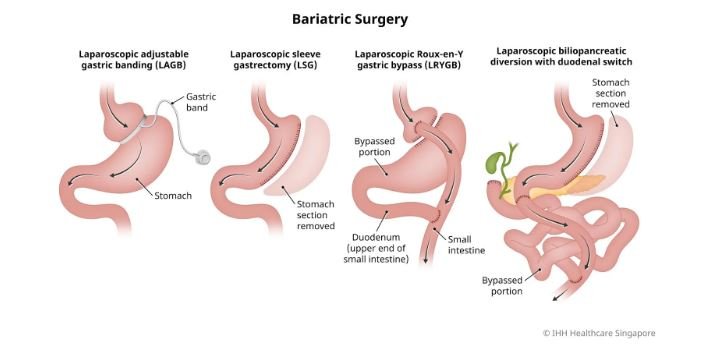

Bariatric Surgery:

- Definition: Weight-loss surgery designed to treat obesity.

- Types:

- Gastric Bypass: Creates a small stomach pouch and bypasses part of the small intestine.

- Sleeve Gastrectomy: Removes a large portion of the stomach, leaving a sleeve-like structure.

- Indications: Morbid obesity with associated health conditions like diabetes or hypertension.

Patient Education and Dietary Modifications

Education:

- Understanding the Condition: Provide comprehensive information about the diagnosis, treatment options, and expected outcomes.

- Medication Adherence: Emphasize the importance of taking medications as prescribed and understanding potential side effects.

Dietary Modifications:

- Personalized Plans: Tailor dietary advice to the specific GI condition and individual patient needs.

- Monitoring and Adjustment: Regularly review and adjust dietary plans based on symptom control and nutritional status.

-

Emergency Care

Acute Abdominal Pain

Assessment:

- History: Includes onset, location, duration, and nature of pain, as well as associated symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, fever).

- Physical Examination: Focuses on palpation for tenderness, rebound tenderness, and guarding, as well as assessing for signs of peritonitis.

Management:

- Initial Stabilization: Includes IV fluids, pain management, and monitoring vital signs.

- Diagnostic Workup: May include imaging studies (e.g., abdominal X-ray, CT scan) and laboratory tests to identify the cause.

- Surgical Consultation: May be necessary for conditions requiring surgical intervention.

Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage

Assessment:

- History: Includes the onset and amount of bleeding, along with any preceding symptoms or risk factors.

- Physical Examination: Focuses on signs of shock (e.g., hypotension, tachycardia) and abdominal findings.

Management:

- Resuscitation: Administer IV fluids and blood products to stabilize the patient.

- Endoscopy: Used for diagnosing and managing upper GI bleeding. Lower GI bleeding may require colonoscopy.

- Medications: May include proton pump inhibitors, vasopressin analogs, or antibiotics depending on the cause of bleeding.

Bowel Obstruction

Assessment:

- History: Includes symptoms such as abdominal pain, distension, vomiting, and changes in bowel movements.

- Physical Examination: Detects abdominal distension, tenderness, and bowel sounds.

Management:

- Nasogastric Tube:

Inserted to relieve gastric pressure and decompress the stomach.

- Imaging: CT scan or abdominal X-ray to confirm the diagnosis and locate the obstruction.

- Surgical Intervention: Required if the obstruction is not relieved with conservative measures or if there is evidence of strangulation or perforation.