N: Diet Therapy for Specific Health Conditions

- Diabetes

Overview of Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by elevated blood glucose levels due to inadequate insulin production, insulin resistance, or both. There are several types of diabetes, including Type 1, Type 2, and gestational diabetes, each requiring different management strategies. Nutrition plays a critical role in diabetes management, with a focus on controlling blood sugar levels, reducing complications, and promoting overall health.

Carbohydrate Counting

Carbohydrate counting is a nutritional strategy used to manage blood glucose levels in individuals with diabetes. It involves tracking the number of carbohydrates consumed in meals and snacks to maintain stable blood sugar levels.

Understanding Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are one of the three macronutrients and are the body’s primary source of energy. They can be categorized into:

- Simple Carbohydrates: These include sugars found in fruits, honey, and processed foods. They are quickly absorbed and can cause rapid spikes in blood glucose levels.

- Complex Carbohydrates: These include starches and fiber found in whole grains, legumes, and vegetables. They are digested more slowly and can help maintain stable blood sugar levels.

Carbohydrate Counting Techniques

- Identifying Carbohydrate Sources: Recognizing foods that contain carbohydrates is crucial. This includes grains, fruits, dairy products, starchy vegetables, and sweets.

- Reading Food Labels: Understanding nutrition labels helps in determining the carbohydrate content of packaged foods, allowing for better meal planning.

- Portion Control: Learning to measure food portions helps in accurately counting carbohydrates. Tools like measuring cups, food scales, and carbohydrate counting apps can assist in this process.

- Daily Carbohydrate Goals: Working with a registered dietitian can help establish individual carbohydrate goals based on activity level, medication, and personal preferences.

Benefits of Carbohydrate Counting

- Improved Blood Glucose Control: By monitoring carbohydrate intake, individuals can prevent spikes in blood glucose levels.

- Flexibility in Meal Planning: Carbohydrate counting allows for a more flexible diet, enabling individuals to enjoy a variety of foods while managing their condition.

- Informed Food Choices: Understanding carbohydrate content empowers individuals to make healthier food choices, promoting overall well-being.

Glycemic Index

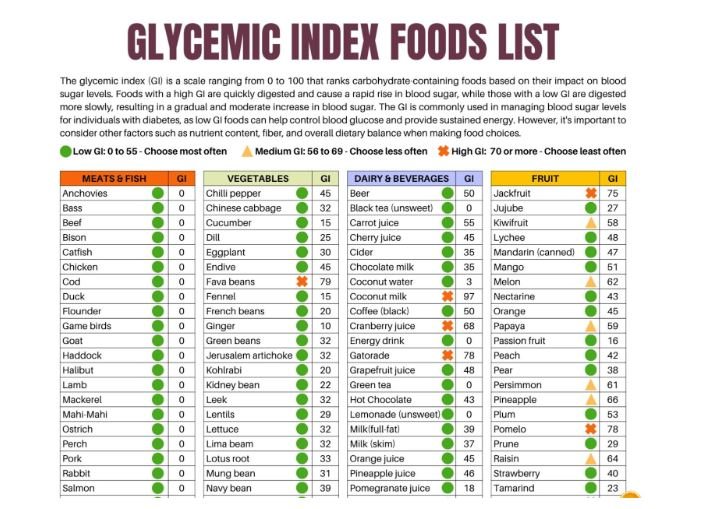

The glycemic index (GI) is a ranking of carbohydrates based on their impact on blood glucose levels. Foods are classified as low, medium, or high GI, influencing meal planning and blood sugar control.

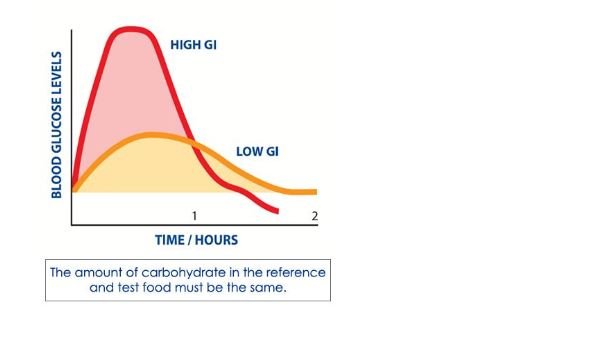

Understanding Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load

- Glycemic Index (GI): Ranges from 0 to 100, where pure glucose has a GI of 100. Foods with a low GI (55 or less) are absorbed slowly, resulting in gradual increases in blood sugar.

- Glycemic Load (GL): Takes into account both the quality and quantity of carbohydrates. It is calculated by multiplying the GI of a food by the amount of carbohydrates in a serving, divided by 100. This provides a more accurate representation of a food’s effect on blood sugar levels.

Using Glycemic Index in Meal Planning

- Choosing Low-GI Foods: Incorporating foods such as whole grains, legumes, fruits, and non-starchy vegetables can help manage blood sugar levels effectively.

- Combining Foods: Pairing high-GI foods with low-GI foods can moderate blood sugar responses. For example, adding protein or healthy fats to a carbohydrate-rich meal can slow digestion and absorption.

- Portion Size: Being mindful of portion sizes is essential, even with low-GI foods. Overeating can lead to elevated blood sugar levels regardless of the GI.

Benefits of Glycemic Index

- Enhanced Blood Sugar Control: Low-GI foods promote better glycemic control, reducing the risk of complications associated with diabetes.

- Sustained Energy Levels: Foods with a low GI provide a more steady release of energy, preventing energy crashes commonly associated with high-GI foods.

- Weight Management: Low-GI diets can promote satiety, helping individuals manage their weight effectively.

Meal Planning for Diabetes

Meal planning is a crucial aspect of diabetes management, focusing on creating balanced meals that stabilize blood sugar levels and meet nutritional needs.

Principles of Meal Planning

- Balanced Meals: A well-balanced meal includes carbohydrates, proteins, and healthy fats. Aim for a variety of foods to ensure adequate nutrient intake.

- Consistent Meal Timing: Eating at regular intervals helps maintain steady blood sugar levels. Incorporating snacks can prevent large fluctuations in glucose levels.

- Portion Control: Understanding portion sizes is vital in managing carbohydrate intake. Using visual cues, such as the plate method, can simplify portion control.

- Incorporating Fiber: High-fiber foods, such as whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and legumes, help regulate blood sugar levels and promote digestive health.

Sample Meal Plan

Breakfast:

- Scrambled eggs with spinach

- Whole-grain toast with avocado

- Fresh berries

Snack:

- Greek yogurt with nuts

Lunch:

- Grilled chicken salad with mixed greens, cherry tomatoes, and olive oil dressing

- Quinoa on the side

Snack:

- Sliced apple with almond butter

Dinner:

- Baked salmon with steamed broccoli

- Brown rice or sweet potato

Snack:

- Carrot sticks with hummus

Benefits of Effective Meal Planning

- Improved Glycemic Control: Thoughtfully planned meals can lead to better blood sugar management.

- Enhanced Nutritional Quality: Meal planning encourages the consumption of a variety of nutrient-dense foods, promoting overall health.

- Increased Adherence: A structured meal plan can simplify daily decisions, making it easier to adhere to dietary recommendations.

Conclusion

Effective management of diabetes requires a comprehensive approach that includes understanding carbohydrate counting, utilizing the glycemic index, and creating balanced meal plans. By empowering individuals with knowledge and practical strategies, healthcare professionals can support them in achieving optimal blood sugar control and enhancing their overall quality of life. With ongoing education and support, individuals with diabetes can successfully navigate their dietary needs, ultimately leading to better health outcomes.

Diet Therapy for Specific Health Conditions

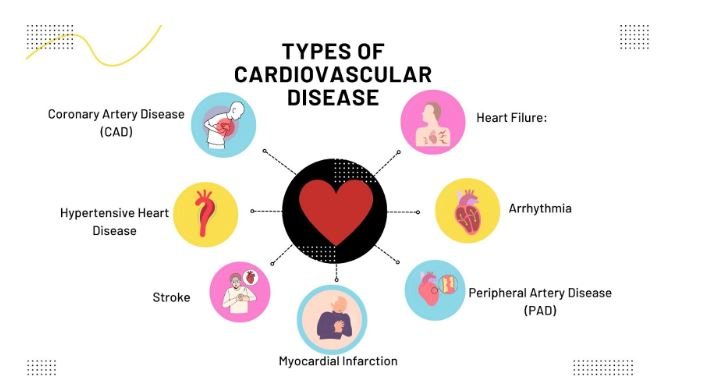

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) encompasses a range of conditions affecting the heart and blood vessels, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, and stroke. Nutrition plays a critical role in preventing and managing these conditions. This chapter explores essential dietary strategies, including low-sodium diets, heart-healthy diets, and cholesterol management, to promote cardiovascular health.

Overview of Cardiovascular Disease

CVD is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Risk factors include high blood pressure, high cholesterol levels, obesity, diabetes, physical inactivity, smoking, and poor dietary choices. A comprehensive approach to dietary management can significantly reduce these risk factors and improve overall heart health.

Low-Sodium Diet

Reducing sodium intake is a fundamental dietary strategy for managing hypertension and other cardiovascular conditions. High sodium consumption is linked to increased blood pressure, leading to higher risks of heart attack and stroke.

Understanding Sodium and Its Effects

- Sodium’s Role in the Body: Sodium is an essential mineral that helps maintain fluid balance, nerve function, and muscle contraction. However, excessive sodium intake can lead to hypertension and increased cardiovascular risk.

- Sources of Sodium: Most dietary sodium comes from processed and packaged foods, including canned soups, frozen meals, snacks, and restaurant foods. Even foods that don’t taste salty, like bread and cereals, can contribute significant sodium.

Recommendations for a Low-Sodium Diet

- Daily Sodium Limit: The American Heart Association recommends limiting sodium intake to less than 2,300 mg per day, with an ideal limit of 1,500 mg for most adults, especially those with hypertension.

- Reading Food Labels: Understanding nutrition labels is vital. Look for sodium content per serving and choose products labeled as “low sodium,” “reduced sodium,” or “no salt added.”

- Fresh Foods Over Processed: Prioritize fresh fruits, vegetables, lean meats, and whole grains, which naturally contain less sodium compared to processed options.

- Flavor Alternatives: Use herbs, spices, citrus, and vinegar to enhance flavor without adding salt. Cooking methods like grilling, roasting, and steaming can also enhance the natural flavors of food.

- Gradual Reduction: Transitioning to a low-sodium diet can be challenging. Gradually reducing sodium intake allows the palate to adjust, making it easier to appreciate the natural flavors of foods.

Benefits of a Low-Sodium Diet

- Improved Blood Pressure Control: Reducing sodium intake can lead to significant decreases in blood pressure for many individuals.

- Decreased Risk of CVD: Lowering blood pressure reduces the risk of heart attacks, strokes, and other cardiovascular events.

- Enhanced Kidney Function: A lower sodium intake may improve kidney function, particularly in individuals with pre-existing kidney conditions.

Heart-Healthy Diet

A heart-healthy diet emphasizes the consumption of nutrient-dense foods that support cardiovascular health. This diet includes a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats.

Components of a Heart-Healthy Diet

- Fruits and Vegetables: Rich in vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, fruits and vegetables are low in calories and high in fiber. Aim for at least five servings per day to support heart health.

- Whole Grains: Whole grains like brown rice, quinoa, whole wheat bread, and oats are excellent sources of fiber and nutrients. They help lower cholesterol levels and maintain healthy blood pressure.

- Healthy Fats: Focus on sources of unsaturated fats, such as avocados, nuts, seeds, and olive oil. Omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish (e.g., salmon, mackerel), walnuts, and flaxseeds, are particularly beneficial for heart health.

- Lean Proteins: Include lean sources of protein, such as poultry, fish, legumes, and plant-based proteins. Limit red meat and processed meats, which can increase cardiovascular risk.

- Low-Fat Dairy: Choose low-fat or fat-free dairy products to provide calcium and vitamin D without excessive saturated fat.

Meal Planning for a Heart-Healthy Diet

- Sample Day of Eating:

- Breakfast: Overnight oats topped with berries and a sprinkle of chia seeds.

- Snack: Sliced apple with almond butter.

- Lunch: Quinoa salad with mixed greens, chickpeas, cherry tomatoes, cucumber, and a lemon-olive oil dressing.

- Snack: Carrot sticks with hummus.

- Dinner: Baked salmon with steamed broccoli and brown rice.

- Snack: A small handful of walnuts.

Benefits of a Heart-Healthy Diet

- Lower Cholesterol Levels: A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains can help reduce LDL cholesterol (the “bad” cholesterol) levels.

- Reduced Inflammation: Foods high in antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids can decrease inflammation, lowering the risk of cardiovascular events.

- Weight Management: A nutrient-dense, low-calorie diet supports healthy weight management, reducing the burden on the cardiovascular system.

Cholesterol Management

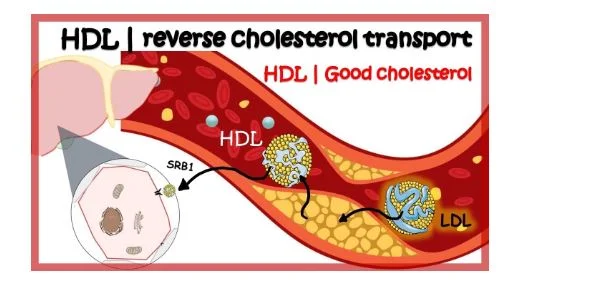

Managing cholesterol levels is crucial for preventing and treating cardiovascular disease. This involves balancing LDL (low-density lipoprotein) and HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol.

Understanding Cholesterol

- Types of Cholesterol:

- LDL Cholesterol:

Often referred to as “bad” cholesterol, high levels of LDL can lead to plaque buildup in arteries, increasing the risk of heart disease.

- HDL Cholesterol: Known as “good” cholesterol, HDL helps remove LDL cholesterol from the bloodstream, reducing cardiovascular risk.

- Sources of Cholesterol: Dietary cholesterol is found in animal products such as meat, dairy, and eggs. However, dietary cholesterol’s impact on blood cholesterol levels varies among individuals.

Strategies for Cholesterol Management

- Incorporating Heart-Healthy Foods:

- Soluble Fiber: Foods rich in soluble fiber, such as oats, barley, beans, lentils, fruits (especially apples and citrus), and vegetables, help lower LDL cholesterol.

- Plant Sterols and Stanols: Found in fortified foods, these compounds can block the absorption of cholesterol and lower LDL levels.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Regular consumption of fatty fish, flaxseeds, and walnuts can help raise HDL cholesterol while lowering triglycerides.

- Limiting Saturated and Trans Fats:

- Saturated Fats: Found in red meat, full-fat dairy products, and certain oils (coconut and palm oil), saturated fats can raise LDL cholesterol levels.

- Trans Fats: Often found in processed and fried foods, trans fats significantly increase LDL cholesterol and should be avoided entirely.

- Regular Physical Activity: Engaging in regular aerobic exercise can help increase HDL cholesterol levels and improve overall cardiovascular health.

- Weight Management: Maintaining a healthy weight can positively influence cholesterol levels, particularly lowering LDL cholesterol and raising HDL cholesterol.

Monitoring Cholesterol Levels

- Regular Screenings: Individuals should have their cholesterol levels checked regularly, typically every four to six years for those with normal levels, and more frequently for those with elevated risk.

- Understanding Lab Results: Knowing the target levels for total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides can help individuals make informed dietary and lifestyle choices.

Benefits of Effective Cholesterol Management

- Reduced Cardiovascular Risk: Effective management of cholesterol levels can significantly decrease the risk of heart disease and stroke.

- Improved Overall Health: Healthy cholesterol levels contribute to better circulation, reduced inflammation, and improved metabolic health.

Conclusion

A comprehensive dietary approach is vital in managing cardiovascular disease. Implementing a low-sodium diet, embracing a heart-healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and managing cholesterol levels through informed food choices can significantly enhance cardiovascular health. By empowering individuals with knowledge and practical strategies, healthcare professionals can support patients in making healthier dietary decisions, ultimately reducing their risk of cardiovascular complications and improving their overall quality of life.

Diet Therapy for Specific Health Conditions

Renal Disease

Renal disease encompasses a range of conditions that impair kidney function, leading to the accumulation of waste products in the body and imbalances in electrolytes and fluid. Proper nutrition is essential in managing renal disease, particularly through protein restriction, fluid management, and maintaining electrolyte balance. This chapter explores these dietary strategies in depth, emphasizing their importance in optimizing kidney health and improving patient outcomes.

Overview of Renal Disease

Renal disease can be classified into acute kidney injury (AKI) and chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is further divided into five stages based on the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). As kidney function declines, patients experience complications such as uremia, fluid overload, and imbalances in electrolytes, necessitating dietary modifications.

Protein Restriction

Protein restriction is a key dietary intervention for managing renal disease. Reducing protein intake can help decrease the workload on the kidneys, slow disease progression, and minimize the accumulation of nitrogenous waste in the blood.

Understanding Protein and Its Role

- Functions of Protein: Protein is vital for building and repairing tissues, producing enzymes and hormones, and supporting immune function. However, when kidney function declines, the body struggles to excrete urea, a byproduct of protein metabolism, leading to elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels.

- Types of Protein:

- Complete Proteins: Found in animal sources such as meat, fish, eggs, and dairy, complete proteins contain all essential amino acids.

- Incomplete Proteins: Found in plant sources such as beans, lentils, and grains, these proteins may lack one or more essential amino acids.

Guidelines for Protein Restriction

- Individualized Protein Intake: Protein needs should be tailored based on the stage of renal disease, body weight, and individual nutritional requirements. Generally, recommendations for protein intake in CKD range from 0.6 to 0.8 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight.

- Choosing High-Quality Protein Sources: Focus on high-quality protein sources that provide essential amino acids while minimizing overall protein intake. Examples include:

- Lean meats (chicken, turkey)

- Fish

- Eggs

- Dairy products (low-fat or non-fat)

- Plant-based proteins (tofu, legumes) in moderation

- Protein Supplements: In certain cases, individuals may need protein supplements to meet their nutritional needs without exceeding their protein restrictions. These should be used under the guidance of a registered dietitian.

- Monitoring Nutritional Status: Regular assessment of nutritional status, including serum albumin levels and overall dietary intake, is essential to ensure adequate protein consumption without overburdening the kidneys.

Benefits of Protein Restriction

- Reduced Uremic Symptoms: Limiting protein intake can decrease the production of uremic toxins, alleviating symptoms such as nausea, fatigue, and itching.

- Slowed Disease Progression: Studies indicate that lower protein intake may slow the progression of CKD, reducing the need for dialysis or transplantation.

- Improved Quality of Life: With proper management of protein intake, individuals may experience improved energy levels, better appetite, and overall enhanced quality of life.

Fluid Management

Fluid management is critical in patients with renal disease, as impaired kidney function affects the body’s ability to regulate fluid balance. Proper fluid intake is essential to prevent complications such as edema, hypertension, and heart failure.

Understanding Fluid Balance

- Role of Kidneys in Fluid Regulation: Healthy kidneys filter excess fluid from the blood, producing urine to maintain homeostasis. When kidney function declines, fluid retention can occur, leading to serious complications.

- Signs of Fluid Overload: Common signs include swelling (edema), shortness of breath, elevated blood pressure, and weight gain. Monitoring these signs is crucial for managing fluid intake.

Guidelines for Fluid Management

- Fluid Intake Assessment: Daily fluid needs should be assessed based on factors such as urine output, body weight, and the presence of edema. In general, fluid intake may need to be restricted to 1 to 2 liters per day in advanced CKD.

- Monitoring Urine Output: Tracking urine output helps determine appropriate fluid intake levels. In cases of oliguric or anuric renal failure, fluid restrictions may be more stringent.

- Educating Patients on Fluid Sources: Patients should be educated about all sources of fluid, including beverages, soups, fruits, and vegetables, as these contribute to total fluid intake.

- Encouraging Hydration with Low-Fluid Foods: Suggesting low-fluid foods such as gelatin, ice pops, and fruits can help individuals meet hydration needs without exceeding fluid restrictions.

Benefits of Proper Fluid Management

- Prevention of Complications: Effective fluid management helps prevent complications related to fluid overload, such as hypertension and heart failure.

- Enhanced Comfort: Managing fluid intake can reduce symptoms of edema and discomfort, improving the patient’s overall well-being.

- Improved Laboratory Values: Maintaining proper fluid balance can positively influence laboratory parameters such as serum electrolytes and blood pressure.

Electrolyte Balance

Electrolyte management is vital in patients with renal disease, as the kidneys play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of potassium, sodium, and phosphorus in the body.

Understanding Key Electrolytes

- Potassium: High potassium levels (hyperkalemia) can lead to life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias. Foods high in potassium include bananas, oranges, potatoes, and tomatoes.

- Sodium: Excess sodium can contribute to hypertension and fluid retention. Processed foods and table salt are significant sources of sodium.

- Phosphorus: Elevated phosphorus levels can lead to bone and cardiovascular problems. Foods high in phosphorus include dairy products, meat, and processed foods.

Guidelines for Managing Electrolyte Balance

- Potassium Management:

- Restrict High-Potassium Foods: Educate patients to limit foods high in potassium, such as bananas, avocados, potatoes, spinach, and nuts, especially in stages of CKD when potassium levels are elevated.

- Choose Lower-Potassium Alternatives: Encourage the consumption of lower-potassium foods such as apples, berries, carrots, and rice.

- Sodium Management:

- Limit Sodium Intake: Aim to reduce sodium intake to less than 2,300 mg per day, with stricter limits for individuals with hypertension or fluid retention.

- Encourage Reading Labels: Patients should be taught to read nutrition labels and choose products with lower sodium content.

- Phosphorus Management:

- Avoid High-Phosphorus Foods: Limit intake of phosphorus-rich foods such as dairy, nuts, and processed meats. Patients should be aware of phosphorus additives in packaged foods.

- Consider Phosphate Binders: In cases of severe hyperphosphatemia, phosphate binders may be prescribed to help manage phosphorus levels.

Benefits of Electrolyte Management

- Prevention of Complications: Effective management of potassium, sodium, and phosphorus levels helps prevent serious complications such as cardiac issues, hypertension, and bone disease.

- Improved Quality of Life: Patients who successfully manage electrolyte levels often experience a better quality of life, with fewer symptoms and improved overall health.

- Optimized Kidney Function: Maintaining electrolyte balance can help slow the progression of renal disease and improve kidney function when possible.

Conclusion

Proper dietary management is essential in the care of patients with renal disease. Through protein restriction, effective fluid management, and electrolyte balance, healthcare professionals can help individuals manage their condition, slow disease progression, and improve overall health outcomes. Empowering patients with knowledge about their dietary needs and fostering collaboration with registered dietitians are crucial components of successful renal disease management.

Diet Therapy for Specific Health Conditions

Gastrointestinal Disorders

Gastrointestinal (GI) disorders encompass a variety of conditions that affect the digestive system, leading to symptoms that can significantly impact quality of life. This chapter delves into three common GI disorders: Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), Celiac Disease, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). Each section covers dietary strategies tailored to manage symptoms, enhance nutritional status, and promote overall well-being.

Overview of Gastrointestinal Disorders

GI disorders can manifest with a range of symptoms, including abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, and malabsorption. Understanding the underlying mechanisms of these disorders and the role of diet is crucial for effective management.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by abdominal discomfort associated with altered bowel habits. It is commonly classified into IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS with constipation (IBS-C), or a mixed pattern (IBS-M). The exact cause of IBS is unknown, but factors such as gut-brain interaction, gut microbiota, and diet play significant roles.

Dietary Approaches for Managing IBS

- Low FODMAP Diet:

- Understanding FODMAPs: FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) are short-chain carbohydrates that can be poorly absorbed in the small intestine. Common high-FODMAP foods include certain fruits (e.g., apples, pears), vegetables (e.g., onions, garlic), legumes, and sweeteners (e.g., honey, high-fructose corn syrup).

- Phases of the Low FODMAP Diet:

- Elimination Phase: Initially, high-FODMAP foods are removed from the diet for 4-6 weeks to assess symptom relief.

- Reintroduction Phase: Gradually reintroduce FODMAPs one at a time to identify specific triggers.

- Personalization Phase: Develop a long-term diet that limits problematic FODMAPs while including those tolerated.

- Other Dietary Adjustments:

- Increased Fiber Intake: For patients with IBS-C, gradually increasing soluble fiber (e.g., oats, chia seeds) can help regulate bowel movements. However, insoluble fiber (e.g., whole grains, nuts) may worsen symptoms in some individuals.

- Regular Meal Timing: Establishing regular meal patterns can help manage symptoms. Smaller, more frequent meals may be beneficial, as they reduce the load on the digestive system.

- Hydration: Adequate fluid intake is essential, especially for those with diarrhea. Aim for 8-10 cups of water daily, adjusting based on activity level and climate.

Benefits of Dietary Management for IBS

- Symptom Relief: Many patients experience significant symptom relief with dietary adjustments, improving quality of life.

- Enhanced Nutritional Status: A well-planned diet helps ensure adequate nutrient intake while managing symptoms.

- Empowerment: Patients gain control over their condition by learning to identify triggers and adapt their diets accordingly.

- Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder triggered by the ingestion of gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye. Ingesting gluten leads to inflammation and damage to the small intestine’s lining, resulting in malabsorption and various symptoms, including diarrhea, weight loss, and nutritional deficiencies.

Dietary Management of Celiac Disease

- Strict Gluten-Free Diet:

- Understanding Gluten: Gluten is found in many common foods, including bread, pasta, cereals, and many processed foods. Cross-contamination can occur during food preparation, making it critical to read labels carefully.

- Identifying Gluten-Free Alternatives: Encourage patients to explore gluten-free grains such as quinoa, rice, millet, and gluten-free oats. Many gluten-free products are available, but patients should be cautious of added sugars and fats.

- Nutritional Considerations:

- Monitoring for Nutritional Deficiencies: Patients with celiac disease are at risk for deficiencies in iron, calcium, fiber, and certain B vitamins due to malabsorption. Regular monitoring of nutritional status and supplementation as needed is essential.

- Incorporating Nutrient-Dense Foods: Emphasize the importance of whole, nutrient-dense foods, including fruits, vegetables, lean proteins, and healthy fats, to ensure a balanced diet.

- Education and Support:

- Celiac Disease Education: Provide education on the nature of the disease, the importance of strict adherence to a gluten-free diet, and how to read food labels effectively.

- Support Groups: Encourage participation in support groups for individuals with celiac disease, which can provide emotional support and practical advice.

Benefits of a Gluten-Free Diet

- Symptom Resolution: Adherence to a strict gluten-free diet leads to symptom resolution and healing of the intestinal lining.

- Improved Nutritional Status: A well-balanced gluten-free diet can help restore nutritional deficiencies and enhance overall health.

- Quality of Life Improvement: Patients often report a significant improvement in quality of life once they eliminate gluten from their diets.

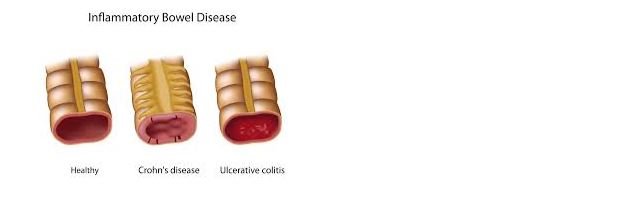

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

IBD, which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, is characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms can vary widely, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue. Dietary management plays a crucial role in managing flare-ups and maintaining remission.

Dietary Strategies for IBD Management

- Tailored Diet During Flare-Ups:

- Low-Residue Diet: During active flare-ups, a low-residue diet may be recommended to reduce bowel stimulation. This involves limiting high-fiber foods (e.g., whole grains, nuts, seeds, raw fruits and vegetables) and opting for low-fiber alternatives.

- Hydration: Increased fluid intake is essential to prevent dehydration, especially during episodes of diarrhea.

- Diet for Maintenance and Remission:

- Balanced Nutrition: Focus on a well-balanced diet rich in macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and fats) and micronutrients (vitamins and minerals) to support overall health.

- Anti-Inflammatory Foods: Incorporate foods known for their anti-inflammatory properties, such as fatty fish (rich in omega-3 fatty acids), nuts, seeds, fruits (e.g., berries), and vegetables (e.g., leafy greens).

- Identifying Trigger Foods:

- Personalized Approach: Patients should be encouraged to maintain a food diary to identify specific trigger foods that may exacerbate symptoms.

- Elimination and Reintroduction: Similar to the low FODMAP approach, patients can benefit from eliminating suspected trigger foods and gradually reintroducing them to monitor for reactions.

- Nutritional Supplements:

- Addressing Nutritional Deficiencies: Due to malabsorption and dietary restrictions, patients with IBD may require supplements, such as vitamin D, calcium, iron, and vitamin B12, to prevent deficiencies.

Benefits of Dietary Management for IBD

- Symptom Control: A tailored diet can help manage symptoms, reduce the frequency and severity of flare-ups, and promote remission.

- Enhanced Nutritional Status: Proper dietary management supports overall nutrition and prevents deficiencies common in IBD patients.

- Improved Quality of Life: Patients who successfully manage their diet often report better quality of life and greater control over their condition.

Conclusion

Dietary management is an integral component of treating gastrointestinal disorders such as IBS, Celiac Disease, and IBD. By implementing tailored dietary strategies, healthcare professionals can help patients manage symptoms, enhance nutritional status, and improve overall quality of life. Education, support, and regular monitoring are essential to empower patients in their dietary choices and promote long-term health.

Diet Therapy for Specific Health Conditions

Cancer

Cancer is a complex group of diseases characterized by the uncontrolled growth and spread of abnormal cells. The diagnosis and treatment of cancer can significantly affect a patient’s nutritional status and overall well-being. This chapter focuses on dietary strategies for nutritional support, managing side effects of treatment, and adapting diets based on the type and stage of cancer.

Overview of Cancer and Nutrition

The relationship between cancer and nutrition is multifaceted. Cancer and its treatments can lead to malnutrition, weight loss, and decreased quality of life. Effective nutritional support is essential for enhancing treatment tolerance, improving recovery, and maintaining the patient’s strength and resilience.

- Nutritional Support

Providing adequate nutrition during cancer treatment is critical for supporting the body’s needs, maintaining muscle mass, and aiding recovery.

- Caloric and Nutrient Needs

Caloric Requirements:

-

- Cancer patients often require higher caloric intake to meet increased metabolic demands caused by the disease and its treatment. The estimated caloric needs can vary based on the type of cancer, treatment modalities, and the patient’s overall health status.

- General recommendations suggest an increase of 20-30% above the estimated basal metabolic rate (BMR) for individuals undergoing active treatment.

- Macronutrient Distribution:

- Carbohydrates: Should comprise 45-65% of total caloric intake. Focus on complex carbohydrates, such as whole grains, legumes, fruits, and vegetables, which provide energy and essential nutrients.

- Proteins: Essential for tissue repair and immune function, protein should account for 15-20% of total caloric intake. Sources include lean meats, poultry, fish, dairy products, legumes, and plant-based proteins (e.g., tofu, tempeh).

- Fats: Healthy fats should make up 20-35% of caloric intake. Emphasize sources of omega-3 fatty acids (e.g., fatty fish, flaxseeds, walnuts) which may have anti-inflammatory properties.

2. Micronutrient Considerations

- Vitamins and Minerals:

- Cancer treatment can lead to deficiencies in essential vitamins and minerals. Antioxidant vitamins (A, C, E) and minerals such as zinc and selenium may support immune function.

- Ensure adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, particularly for patients undergoing treatments that affect bone health.

- Hydration:

- Adequate fluid intake is crucial to prevent dehydration, especially in patients experiencing vomiting or diarrhea. Encourage clear fluids, broths, and electrolyte solutions as needed.

- Dietary Strategies

- Frequent Small Meals:

- Instead of three large meals, encourage patients to consume small, frequent meals throughout the day. This approach can help manage appetite and improve nutrient intake.

- Energy-Dense Foods:

- Incorporate energy-dense foods, such as nut butters, avocados, full-fat dairy products, and protein shakes, to help meet caloric needs without overwhelming the patient’s appetite.

- Individualized Meal Plans:

- Develop personalized meal plans that consider food preferences, cultural dietary practices, and specific treatment regimens.

3. Managing Side Effects

Cancer treatment can lead to various side effects that impact a patient’s ability to eat and maintain proper nutrition. Addressing these side effects through dietary modifications is essential for improving quality of life.

- Nausea and Vomiting

- Dietary Adjustments:

- Recommend small, bland meals that are easier to digest, such as crackers, rice, bananas, and applesauce.

- Encourage the consumption of ginger tea, peppermint, or lemon to alleviate nausea.

- Timing of Meals:

- Advise patients to eat when they feel least nauseated, which may vary from person to person. Eating cold or room-temperature foods can also help reduce nausea.

- Loss of Appetite

- Enhancing Appeal of Food:

- Encourage the use of herbs and spices to enhance the flavor of meals. Visually appealing presentations can also stimulate appetite.

- Suggest nutrient-dense snacks, such as smoothies or protein bars, that are easier to consume when appetite is low.

- Fostering Positive Eating Environments:

- Promote a relaxed and enjoyable eating environment. Social meals with family or friends can encourage eating and improve mood.

- Difficulty Swallowing (Dysphagia)

- Texture Modifications:

- For patients with swallowing difficulties, recommend modifications in food texture. Soft, moist foods are easier to swallow, while pureed foods can prevent choking hazards.

- Consider using thickening agents for liquids to improve safety during swallowing.

- Nutritional Supplements:

- Use commercial nutritional supplements or homemade smoothies to provide essential nutrients without the need for chewing.

4. Special Diets

Dietary modifications may vary based on the type and stage of cancer, as well as treatment regimens. Special diets tailored to individual needs can help manage symptoms and promote recovery.

- Cancer-Specific Dietary Considerations

- Breast Cancer:

- Emphasize a plant-based diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats to support overall health and reduce recurrence risk. Foods high in phytonutrients, such as berries, cruciferous vegetables, and flaxseeds, may be beneficial.

- Colorectal Cancer:

- A high-fiber diet is often recommended to promote bowel regularity and overall gut health. Focus on whole grains, legumes, and fresh fruits and vegetables while avoiding processed meats.

- Prostate Cancer:

- Consider a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids and low in saturated fats. Incorporate foods like fatty fish, nuts, and seeds while limiting dairy and red meat.

- Lung Cancer:

- Emphasize the importance of antioxidants and vitamins, particularly vitamins A, C, and E, to support immune function. Foods rich in these nutrients include carrots, sweet potatoes, citrus fruits, and nuts.

- Special Considerations During Treatment

Chemotherapy:

- Patients undergoing chemotherapy may benefit from avoiding foods that are more likely to harbor bacteria, such as raw fruits and vegetables or undercooked meats. Focus on well-cooked foods and avoid unpasteurized dairy products.

Radiation Therapy:

- For patients receiving radiation, especially to the head and neck area, soft, moist foods may be necessary to accommodate mouth sores or difficulty swallowing. Smoothies, soups, and pureed foods can be beneficial.

Importance of Monitoring and Support

- Regular Nutritional Assessments:

- Conduct regular assessments of weight, dietary intake, and nutritional status to identify changes and make necessary adjustments to the diet.

- Interdisciplinary Approach:

- Collaborate with a dietitian, oncologist, and nursing staff to provide comprehensive support for the patient’s nutritional needs throughout treatment.

Conclusion

Nutrition plays a vital role in the care of cancer patients, affecting their treatment outcomes and quality of life. By providing adequate nutritional support, managing side effects, and adapting diets based on individual needs, healthcare professionals can enhance recovery and improve overall health. Continuous education, support, and individualized care are key components in successfully managing the nutritional aspects of cancer treatment.