Mental Health Assessment

The mental health assessment is a critical component of psychiatric nursing care. It provides comprehensive information that is essential for developing a diagnosis, creating a treatment plan, and monitoring progress. A mental health assessment includes multiple facets: a detailed Mental Status Examination (MSE) and thorough history taking. These two components offer insight into the patient’s psychological state, cognitive function, and background, which can help in identifying psychiatric conditions and in delivering tailored interventions.

-

Initial Assessment

Mental Status Examination (MSE)

The Mental Status Examination (MSE) is a structured way of observing and describing a patient’s current state of mind. It includes several domains, each providing crucial information about the patient’s mental functioning:

1.1. Appearance

This involves observing how the patient presents themselves physically. It includes factors such as:

- Grooming: Are they well-groomed or disheveled? Poor grooming might indicate depression, cognitive decline, or schizophrenia.

- Hygiene: Does the patient exhibit good personal hygiene? Neglect of hygiene can suggest a lack of self-care, often seen in severe mental illness.

- Clothing: Is the clothing appropriate for the weather and context? Inappropriate dressing could be a sign of impaired judgment or a manic episode.

- Posture and Gait: Posture and movement can provide insights. For instance, a slouched posture might indicate depression, while psychomotor agitation (fidgeting, pacing) may suggest anxiety or mania.

1.2. Behavior

Observing behavior provides a window into the patient’s mental and emotional state:

- Eye contact: Is the patient avoiding eye contact, making excessive eye contact, or maintaining normal eye contact? Avoidance could be a sign of depression, shame, or paranoia.

- Psychomotor Activity: This refers to the patient’s movements. Psychomotor retardation may be seen in depression, while hyperactivity or agitation may be seen in mania or anxiety.

- Cooperation and Engagement: Is the patient cooperative or hostile? Engaging or withdrawn? These behaviors can indicate rapport, willingness to engage, or underlying mistrust, often seen in psychotic disorders.

- Movement Abnormalities: Presence of tics, tremors, or catatonic behaviors may indicate neurological or psychiatric conditions like Parkinson’s disease or catatonic schizophrenia.

1.3. Speech

Speech patterns can reveal cognitive and emotional disturbances:

- Rate of Speech: Is speech rapid (pressured speech, often seen in mania) or slow (indicative of depression)?

- Tone: A monotone voice might reflect a lack of affect (flat affect), which could be seen in schizophrenia or major depressive disorder.

- Volume: Is the patient speaking too loudly or softly? Speaking loudly could indicate mania or anger, while a soft voice may reflect anxiety or depression.

- Coherence: Are the thoughts expressed in a logical, coherent manner, or is there evidence of disorganized speech, such as flight of ideas (common in mania) or tangentiality (seen in schizophrenia)?

1.4. Mood

Mood is the sustained emotional state reported by the patient:

- Self-reported mood: This is the patient’s subjective experience of their emotional state, such as “I feel sad,” “I feel angry,” or “I feel happy.”

- Mood descriptors: Can range from euthymic (normal mood), dysphoric (depressed or anxious), euphoric (excessively happy), to irritable.

1.5. Affect

Affect refers to the observable emotional expression:

- Appropriateness: Is the affect appropriate to the content of discussion? A patient laughing inappropriately while discussing a traumatic event may exhibit inappropriate affect.

- Range and Intensity: A broad range of affect is normal, while restricted affect may indicate emotional blunting, often seen in schizophrenia. Exaggerated intensity might indicate mania.

- Stability: Mood lability, or rapid shifts in affect, is often seen in borderline personality disorder.

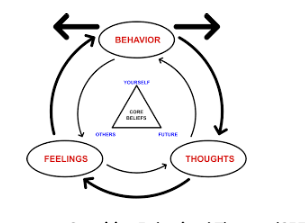

1.6. Thought Process

This evaluates how thoughts are organized:

- Logical and Coherent: Normal thought processes are logical and flow in a coherent manner.

- Disorganized Thinking: This can include tangentiality, flight of ideas, or loose associations. Disorganized thought processes are common in schizophrenia and mania.

- Perseveration: This refers to the repetition of a particular response (word, phrase, or gesture) despite the absence or cessation of a stimulus, often seen in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

- Circumstantiality: The patient provides excessive unnecessary detail but eventually makes their point, commonly seen in anxiety disorders.

1.7. Thought Content

What the patient is thinking about is as important as how they think:

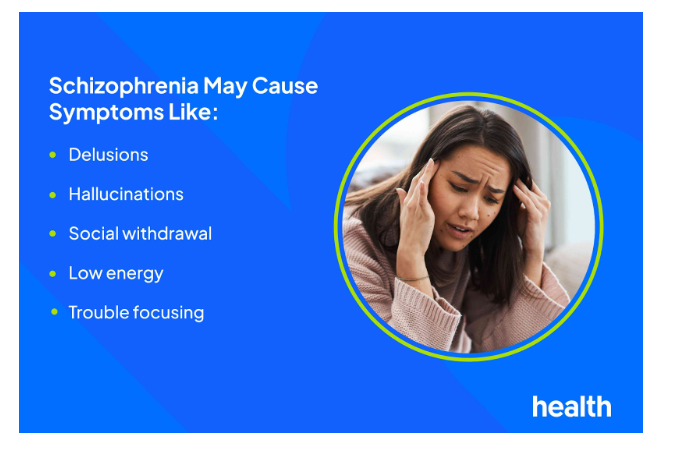

- Delusions: Fixed, false beliefs that are not grounded in reality, such as persecutory delusions (e.g., “People are out to get me”) or grandiose delusions (e.g., “I have special powers”).

- Obsessions: Recurrent, intrusive thoughts, often seen in OCD.

- Phobias: Irrational fears that the patient may or may not recognize as excessive.

- Suicidal or Homicidal Thoughts: An important area to assess, especially in mood disorders and psychosis.

1.8. Perception

This domain covers how patients interpret their environment:

- Hallucinations: Sensory perceptions without external stimuli. These can be auditory (most common in schizophrenia), visual, tactile, or olfactory.

- Illusions: Misinterpretations of actual external stimuli, such as mistaking a coat rack for a person.

1.9. Cognition

Cognitive function is critical to assessing overall mental status:

- Orientation: Is the patient oriented to time, place, person, and situation? Disorientation is often seen in delirium or dementia.

- Attention and Concentration: The ability to focus and maintain attention. Poor concentration may indicate depression, anxiety, or attention deficit disorders.

- Memory: Assessing short-term and long-term memory. Patients with dementia may have difficulty recalling recent events.

- Abstract Thinking: The ability to think abstractly is often tested by interpreting proverbs. Concrete thinking may suggest schizophrenia or cognitive impairments.

- Judgment: Does the patient make decisions that reflect an understanding of the consequences? Poor judgment is common in mood disorders and substance use disorders.

- Insight: Does the patient understand that they have a mental health issue and how it affects their functioning? Lack of insight is frequently seen in psychotic disorders.

-

History Taking

The second major component of the initial mental health assessment is history taking, which provides context to the MSE findings. A comprehensive psychiatric history involves gathering information across multiple domains, including personal history, family history, psychiatric history, and social history.

2.1. Personal History

This provides background on the patient’s life and includes:

- Developmental History: Information about birth and early childhood development, including any developmental delays, can provide insight into potential lifelong cognitive or emotional difficulties.

- Educational Background: Understanding the patient’s educational experience, including any learning disabilities or academic challenges, may shed light on cognitive function or long-standing psychological issues.

- Work History: A consistent work history may suggest stability, while frequent job changes or periods of unemployment may indicate underlying psychiatric issues like depression, bipolar disorder, or substance use disorders.

- Medical History: Any history of chronic illnesses, surgeries, or injuries (e.g., traumatic brain injuries) can impact mental health and are essential to note.

- Trauma History: History of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse can contribute to a range of psychiatric conditions, including PTSD, depression, and anxiety.

2.2. Family History

Family history helps in identifying genetic predispositions:

- Psychiatric Conditions: A history of mental health disorders in the family (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder) increases the risk of these conditions in the patient.

- Substance Use Disorders: Familial patterns of substance use can indicate genetic and environmental influences on the patient’s own behavior.

- Family Dynamics: Family relationships can significantly impact mental health. Enmeshed or conflict-ridden relationships may contribute to anxiety, mood disorders, or personality disorders.

2.3. Psychiatric History

A detailed psychiatric history should be obtained:

- Previous Diagnoses: Past diagnoses can provide insight into the patient’s current condition and treatment needs.

- Previous Treatments: This includes both pharmacological (e.g., antidepressants, antipsychotics) and psychotherapeutic (e.g., CBT, DBT) interventions. Treatment response and compliance should also be noted.

- Hospitalizations: A history of psychiatric hospitalizations may indicate the severity of past mental health crises.

- Suicidal or Homicidal Ideation: Past suicidal or homicidal behavior is a strong risk factor for future attempts.

2.4. Social History

Social history explores the patient’s environment and lifestyle:

- Living Situation: Is the patient living alone or with others? Are they in a stable environment? Social isolation can worsen depression and anxiety, while chaotic living situations can trigger or exacerbate mental illness.

- Support Systems: A strong support network of family and friends can provide resilience against mental illness, while a lack of support can increase vulnerability.

- Substance Use: Substance use, including alcohol, drugs, or prescription medications, should be thoroughly explored as these can influence mood, cognition, and overall functioning.

- Legal Issues: Legal problems, such as arrests, imprisonment, or ongoing court cases, can add significant stress and are often associated with substance use or antisocial behavior.

- Cultural and Religious Beliefs: Cultural norms and religious beliefs can significantly influence a patient’s perception of mental illness, coping strategies, and treatment acceptance.

Conclusion

The Initial Assessment in psychiatric nursing, which includes the Mental Status Examination (MSE) and History Taking, forms the foundation of understanding the patient’s mental health status. Each component, from the assessment of mood and affect to the exploration of cognitive function and thought content, provides essential data that helps shape diagnosis and care planning. Thorough history taking offers a broader context, enriching the assessment with personal, familial, and social dimensions. The more detailed and insightful the assessment, the more targeted and effective the nursing interventions will be.

Mental Health Assessment

An integral part of psychiatric nursing is the ability to accurately assess mental health conditions using diagnostic tools and scales. These tools provide standardized, evidence-based methods to screen for and assess the severity of various mental health conditions. In this chapter, we will cover two major aspects: Screening Tools and Diagnostic Criteria. Screening tools help nurses identify potential mental health issues, while diagnostic criteria, particularly the DSM-5, guide clinicians in making precise psychiatric diagnoses.

The goal is to provide an in-depth exploration of both categories, covering their usage, limitations, and role in mental health nursing practice.

-

Diagnostic Tools and Scales

1.1. Screening Tools

Screening tools are essential in psychiatric nursing for the early identification of mental health issues. They are not diagnostic but serve as a first step to detect potential conditions that warrant further assessment. These tools are often brief, easy to administer, and can be scored quickly. Among the most widely used screening tools are the PHQ-9 (for depression), GAD-7 (for anxiety), and CAGE (for substance use). Below is an in-depth analysis of each tool.

1.1.1. PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire-9)

The PHQ-9 is one of the most common and widely used screening tools for depression. It is a 9-item self-report measure that assesses the frequency of depressive symptoms over the last two weeks. It is based on the diagnostic criteria for depression as outlined in the DSM-5, making it a valuable tool for detecting major depressive disorder.

- Structure: Each item on the PHQ-9 corresponds to a key symptom of depression (e.g., anhedonia, sleep disturbances, fatigue), and the patient rates the severity of each symptom on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day).

- Scoring: The total score ranges from 0 to 27. Scores of 5, 10, 15, and 20 correspond to mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depression, respectively.

- Use in Clinical Settings: The PHQ-9 is frequently used in both primary care and psychiatric settings. It can serve as a baseline for determining the severity of depression and tracking progress over time. It is also useful for evaluating treatment efficacy.

- Strengths: The PHQ-9 is highly accessible, easy to administer, and has strong psychometric properties, with high sensitivity and specificity for detecting major depressive disorder.

- Limitations: While the PHQ-9 is useful for identifying depression, it is not diagnostic. A high score should prompt further evaluation, including a clinical interview, to confirm the diagnosis. Additionally, it does not assess other forms of depression, such as dysthymia.

Example of PHQ-9 Items:

- Little interest or pleasure in doing things.

- Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless.

- Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much.

Clinical Considerations for PHQ-9:

- Cultural Sensitivity: Depression may manifest differently in various cultural contexts, and somatic symptoms (such as fatigue or pain) may be more prominent in some groups. Nurses must be culturally aware when interpreting PHQ-9 results.

- Integration into Nursing Practice: Nurses should use the PHQ-9 as part of a broader assessment, considering other factors such as the patient’s medical history, social circumstances, and risk factors for depression.

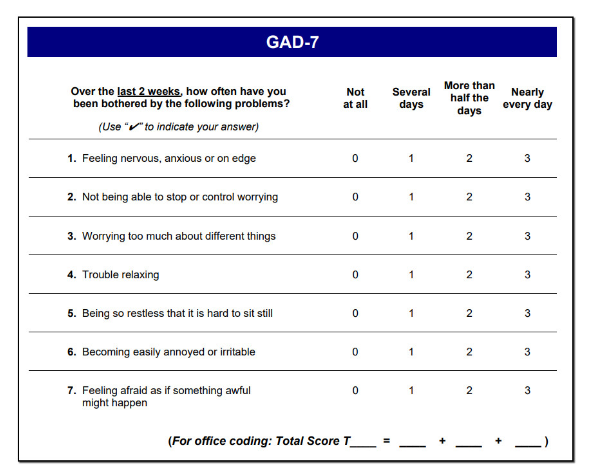

1.1.2. GAD-7 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7)

The GAD-7 is a widely used screening tool for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Like the PHQ-9, it is a self-report measure that assesses the severity of anxiety symptoms over the last two weeks.

- Structure: The GAD-7 consists of 7 items that correspond to the core symptoms of GAD, such as excessive worry, irritability, and restlessness. Each symptom is rated on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day).

- Scoring: Scores range from 0 to 21. Scores of 5, 10, and 15 correspond to mild, moderate, and severe anxiety, respectively.

- Use in Clinical Settings: The GAD-7 is frequently used in primary care and psychiatric settings to identify patients who may be experiencing significant anxiety symptoms. It is also useful in tracking symptom changes over time.

- Strengths: The GAD-7 has excellent psychometric properties and is easy to administer. It is highly sensitive to GAD but also useful for detecting other anxiety disorders, such as panic disorder or social anxiety disorder.

- Limitations: Similar to the PHQ-9, the GAD-7 is a screening tool and not diagnostic. A high score should lead to a more comprehensive assessment. Additionally, the tool does not differentiate between different anxiety disorders (e.g., panic disorder vs. GAD).

Example of GAD-7 Items:

- Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge.

- Not being able to stop or control worrying.

- Worrying too much about different things.

Clinical Considerations for GAD-7:

- Co-morbidities: Anxiety often co-exists with depression, and many patients who score high on the GAD-7 may also have high PHQ-9 scores. Nurses should assess both conditions simultaneously and consider dual treatments.

- Case Study: A patient with a GAD-7 score of 17 (indicating severe anxiety) may require both pharmacological interventions (such as SSRIs) and psychotherapeutic approaches (such as CBT) to manage symptoms effectively.

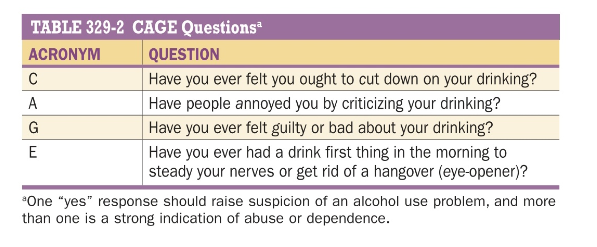

1.1.3. CAGE Questionnaire

The CAGE questionnaire is a brief, 4-item screening tool designed to detect potential alcohol abuse and substance use disorders. It is primarily used in clinical settings to assess patients for problematic drinking but can also be adapted for other substances.

- Structure: The acronym CAGE stands for the four questions asked: Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, and Eye-opener. Each question assesses a key aspect of substance use that may indicate problematic behavior.

- Scoring: Each “yes” response is scored as 1 point. A total score of 2 or higher suggests that the patient may have a substance use disorder and warrants further investigation.

- Use in Clinical Settings: The CAGE questionnaire is particularly useful in busy healthcare environments where a quick screen is needed to identify patients who may have issues with alcohol or drugs.

- Strengths: The brevity of the CAGE questionnaire makes it ideal for use in general medical settings. It is highly sensitive and specific for detecting alcohol abuse.

- Limitations: The CAGE questionnaire is not designed to assess the severity of substance use disorders, nor does it differentiate between different types of substances.

Example of CAGE Questions:

- Have you ever felt you should cut down on your drinking?

- Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking?

- Have you ever felt bad or guilty about your drinking?

- Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning (an eye-opener) to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover?

Clinical Considerations for CAGE:

- Follow-up: A positive CAGE score should prompt more detailed questioning about the patient’s drinking habits, such as frequency and quantity of alcohol use. Further assessment tools like the AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) can provide a more comprehensive picture of the patient’s alcohol use.

- Cultural Context: Nurses must be aware of cultural and societal norms regarding alcohol use when interpreting CAGE results. What may be considered problematic in one culture may not be seen as such in another.

1.2. Diagnostic Criteria (DSM-5)

The DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition) is the gold standard for diagnosing mental health conditions. It provides clinicians with clear diagnostic criteria, ensuring consistency and accuracy across different healthcare settings. Below, we explore the DSM-5 criteria for three common mental health disorders: depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and substance use disorder.

1.2.1. DSM-5 Criteria for Major Depressive Disorder

To be diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD), the DSM-5 requires that a patient experience five or more of the following symptoms during the same 2-week period, and at least one of the symptoms must be either depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure:

- Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day.

- Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in almost all activities.

- Significant weight loss or gain, or decrease or increase in appetite.

- Insomnia or hypersomnia.

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation.

- Fatigue or loss of energy.

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt.

- Diminished ability to think or concentrate.

- Recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation, or a suicide attempt.

Clinical Implications for Nurses:

- Screening and Assessment: Using tools like the PHQ-9 can help nurses identify patients at risk for MDD. The DSM-5 criteria then provide a framework for confirming the diagnosis.

- Treatment: Nurses play a crucial role in the treatment of MDD, including administering antidepressants, educating patients about therapy options, and providing support for lifestyle changes.

1.2.2. DSM-5 Criteria for Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

To be diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, the DSM-5 requires that excessive anxiety and worry (about various events or activities) occur more days than not for at least 6 months. Additionally, the anxiety must be associated with at least three of the following six symptoms:

- Restlessness or feeling keyed up or on edge.

- Being easily fatigued.

- Difficulty concentrating or mind going blank.

- Irritability.

- Muscle tension.

- Sleep disturbance (difficulty falling or staying asleep, or restless, unsatisfying sleep).

Clinical Implications for Nurses:

- Screening and Assessment: The GAD-7 is an excellent tool to help nurses identify patients with potential GAD. If the score suggests significant anxiety, the DSM-5 criteria should guide the formal diagnosis.

- Interventions: Nurses should be involved in administering medications such as SSRIs, providing patient education about cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and offering relaxation techniques to reduce anxiety symptoms.

1.2.3. DSM-5 Criteria for Substance Use Disorder

The DSM-5 defines substance use disorder as a problematic pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by at least two of the following criteria within a 12-month period:

- Taking the substance in larger amounts or for longer than intended.

- Wanting to cut down or stop using the substance but not being able to.

- Spending a lot of time obtaining, using, or recovering from the substance.

- Craving the substance.

- Failing to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home due to substance use.

- Continuing to use the substance despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the effects of the substance.

- Giving up important social, occupational, or recreational activities because of substance use.

- Using the substance in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Continuing to use the substance despite knowledge of a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem caused or exacerbated by the substance.

- Developing tolerance.

- Experiencing withdrawal symptoms.

Clinical Implications for Nurses:

- Screening and Diagnosis: The CAGE questionnaire is a useful starting point for identifying substance use disorders, but DSM-5 criteria provide the detailed framework for diagnosis.

- Treatment: Nurses play a vital role in substance use treatment, including administering detoxification medications, providing counseling, and supporting patients in rehabilitation programs.

Conclusion

In mental health nursing, screening tools such as the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and CAGE questionnaire serve as the first step in identifying potential mental health disorders. They allow nurses to gather initial information on a patient’s emotional and psychological state. However, for an accurate diagnosis, the DSM-5 criteria must be applied. The DSM-5 provides a comprehensive and standardized approach to diagnosing mental health conditions like major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and substance use disorder.

Risk Assessment

Mental health assessments form the foundation for diagnosing and managing psychiatric disorders. In this chapter, we will focus on Risk Assessment—a critical component in the evaluation of patients’ mental well-being, particularly those at risk of self-harm, suicide, or harm to others. This content will thoroughly explore self-harm and suicide risk, including the identification of risk factors, warning signs, and the assessment of intent, followed by an examination of how to assess the potential for aggression or violence toward others.

The chapter is designed to cover these subtopics in great depth, offering practical insights for nurses in psychiatric settings, who are often the first point of contact for individuals at risk.

-

Self-Harm and Suicide Risk Assessment

Self-harm and suicide are major public health concerns, and nurses are essential in identifying individuals at risk. Understanding risk factors, recognizing warning signs, and conducting a thorough assessment of intent are necessary skills for psychiatric nursing. Early intervention and appropriate management can save lives.

1.1. Understanding Self-Harm and Suicide

Self-harm refers to intentional injury inflicted on oneself, often without the intent to die. However, it is a strong predictor of future suicide attempts. Suicide, on the other hand, is the act of intentionally causing one’s death. Understanding the complex interplay between self-harm and suicide is essential for proper assessment and intervention.

- Self-Harm: Typically involves actions such as cutting, burning, or hitting oneself. Patients engaging in self-harm may not have suicidal intent, but the act is often associated with emotional distress or psychological pain.

- Suicide: Suicide ideation (SI) refers to thinking about, considering, or planning suicide. Suicide attempts (SA) involve active efforts to end one’s life, with varying degrees of lethality.

1.2. Identifying Risk Factors for Suicide and Self-Harm

Identifying risk factors helps nurses detect individuals who may be at risk for self-harm or suicide. These risk factors are typically categorized into biological, psychological, and sociocultural domains. Nurses must be able to recognize multiple risk factors to make an informed assessment.

1.2.1. Biological Risk Factors

- Mental Health Disorders:

- Major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and borderline personality disorder are strongly linked with self-harm and suicide risk.

- Substance use disorders (e.g., alcohol or opioid dependence) increase impulsivity, lowering the threshold for self-harm and suicide attempts.

- Chronic Physical Illness:

- Chronic illnesses such as cancer, chronic pain conditions, or neurological diseases (e.g., multiple sclerosis) are risk factors due to prolonged suffering and hopelessness.

-

Genetic Vulnerability:

- A family history of suicide or psychiatric illness can predispose individuals to suicidal behavior.

1.2.2. Psychological Risk Factors

- Previous Suicide Attempts:

- One of the most significant risk factors for future suicide is a history of previous suicide attempts.

- Hopelessness and Despair:

- Individuals experiencing overwhelming feelings of hopelessness or emotional numbness are at high risk. Chronic negative thinking and a lack of perceived control over one’s future can drive suicide ideation.

- Personality Traits:

- Impulsivity, perfectionism, or low frustration tolerance can increase the likelihood of both self-harm and suicide attempts.

1.2.3. Sociocultural Risk Factors

- Isolation and Lack of Social Support:

- Loneliness, social isolation, and the absence of a support system contribute significantly to the risk of suicide. Adolescents, the elderly, and people from marginalized communities may be particularly vulnerable.

- Cultural Beliefs and Stigmatization:

- Certain cultural contexts may either elevate or mitigate suicide risk. For example, cultural stigmatization of mental illness can discourage individuals from seeking help.

- Unemployment and Financial Stress:

- Economic hardships, especially in vulnerable populations, contribute to increased stress, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation.

1.3. Recognizing Warning Signs for Self-Harm and Suicide

The warning signs of self-harm and suicide are often apparent in a patient’s behavior, mood, and verbalizations. Recognizing these signs is essential for timely intervention.

1.3.1. Behavioral Warning Signs

- Increased Risky Behaviors:

- Patients may engage in reckless or self-destructive behaviors such as driving dangerously, substance abuse, or giving away personal belongings.

- Withdrawal from Social Life:

- Social withdrawal from friends, family, and usual activities is a prominent warning sign. Patients may isolate themselves and exhibit a marked lack of interest in previously enjoyed activities.

- Sudden Calmness After Agitation:

- In some cases, a sudden sense of peace following severe anxiety may indicate that a patient has decided to end their life.

1.3.2. Emotional and Cognitive Warning Signs

- Verbal Cues:

- Expressions like “I wish I were dead” or “People would be better off without me” are clear indicators of suicidal intent.

- Anxiety and Agitation:

- Anxiety, especially when paired with insomnia or increased agitation, can signal suicidal ideation.

- Hopelessness:

- Feelings of hopelessness and worthlessness are strong emotional predictors of suicidal behavior. Nurses must carefully listen to patients expressing an inability to envision a positive future.

1.4. Assessing Suicide Intent

Suicide intent refers to how seriously the individual considers or plans suicide. Nurses must distinguish between passive suicidal ideation (e.g., “I wish I could go to sleep and never wake up”) and active suicidal ideation (e.g., “I am planning to take an overdose”).

1.4.1. Direct Questions

Nurses should ask direct, non-judgmental questions to assess the seriousness of suicide ideation:

- “Are you thinking about killing yourself?”

- “Do you have a plan for how you would do it?”

- “Have you taken any steps to prepare (e.g., stockpiling pills or writing a note)?”

1.4.2. Assessing the Plan’s Specificity

The more detailed and specific the suicide plan, the greater the risk of suicide completion. Nurses should assess:

- Method: What means does the patient plan to use (e.g., overdose, firearm, hanging)?

- Access: Does the patient have access to their planned method?

- Timing: Has the patient set a specific time or date for the suicide attempt?

1.4.3. Lethality of the Method

Certain suicide methods (e.g., firearms, hanging) have a higher lethality rate, making them more concerning. Nurses must assess the lethality of the patient’s planned method to determine the immediate level of risk.

1.5. Interventions for Self-Harm and Suicide Risk

Effective interventions involve both short-term safety measures and long-term strategies to address underlying issues.

1.5.1. Short-Term Safety Measures

- Hospitalization:

- Immediate hospitalization may be required for patients with high suicide risk to ensure their safety.

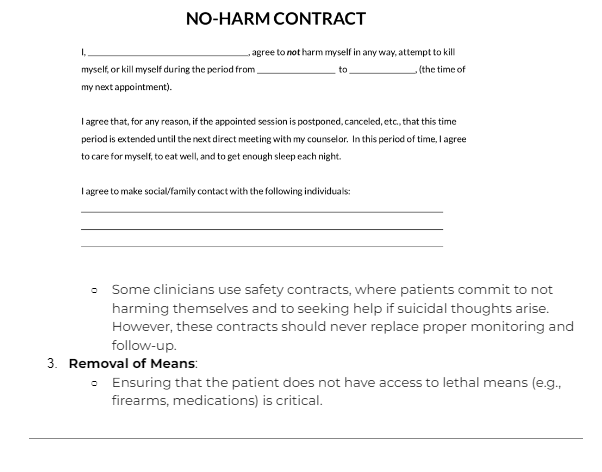

- Safety Contracts:

- Some clinicians use safety contracts, where patients commit to not harming themselves and to seeking help if suicidal thoughts arise. However, these contracts should never replace proper monitoring and follow-up.

- Removal of Means:

- Ensuring that the patient does not have access to lethal means (e.g., firearms, medications) is critical.

1.5.2. Long-Term Interventions

- Pharmacotherapy:

- Medications such as SSRIs and mood stabilizers are commonly used to manage underlying psychiatric conditions like depression and bipolar disorder. Antipsychotics may be necessary in cases of psychosis-related suicide risk.

1.1 Psychotherapy:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is one of the most effective forms of therapy for reducing suicide risk. Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) is particularly effective for individuals with borderline personality disorder who exhibit chronic self-harming behaviors.

1.2 Follow-Up Care:

- Regular follow-up care, including psychosocial interventions and case management, is essential to ensure long-term safety and recovery.

-

Risk to Others: Assessing Potential for Aggression or Violence

Assessing a patient’s risk of harming others involves evaluating their potential for aggression or violence. Nurses must recognize behaviors and underlying psychiatric conditions that may contribute to violent tendencies. This section will explore how to assess these risks and intervene effectively.

2.1. Understanding Aggression and Violence in Psychiatric Settings

Aggression can manifest as verbal hostility, threats, or physical violence. It is particularly prevalent in individuals with specific psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or substance abuse. Recognizing early signs of aggression is vital for preventing harm to staff, other patients, and the individual themselves.

2.2. Identifying Risk Factors for Aggression and Violence

Several risk factors can predispose an individual to violence. These can be grouped into personal history, psychiatric symptoms, and environmental triggers.

2.2.1. Personal History Risk Factors

- History of Violence:

- A history of previous violent behavior is the most significant predictor of future aggression. This may include domestic violence, criminal behavior, or assaults on healthcare staff.

- Childhood Abuse or Trauma:

- Individuals who experienced abuse or trauma in childhood are more likely to exhibit aggressive behaviors in adulthood.

2.2.2. Psychiatric Symptoms and Disorders

- Psychosis:

- Individuals experiencing hallucinations, delusions (particularly paranoid delusions), or severe agitation are at increased risk for aggression. For instance, a patient who believes they are being persecuted may act violently in self-defense.

- Mania:

- During manic episodes, individuals may become hyperactive, irritable, and impulsive, leading to aggressive outbursts.

- Substance Abuse:

- The use of alcohol or stimulants (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine) is strongly associated with impulsivity and violence.

2.2.3. Environmental and Situational Triggers

- Overcrowded or Chaotic Environments:

- In psychiatric wards, overcrowded, noisy, or disorganized environments can heighten agitation, increasing the risk of violent incidents.

- Perceived Threats:

- Perceived disrespect, boundary violations, or confrontations with authority figures can trigger aggression in at-risk individuals.

2.3. Recognizing Early Warning Signs of Aggression

Early warning signs of aggression include behavioral, emotional, and physical indicators. Recognizing these signs early can allow for de-escalation before violence occurs.

2.3.1. Behavioral Signs

- Verbal Hostility:

- Angry or hostile verbalizations, including threats or yelling, may precede violent acts. Nurses should pay attention to escalating speech patterns.

- 2 Pacing and Restlessness:

- Patients who are pacing or exhibiting restless body movements may be showing signs of mounting aggression.

2.3.2. Emotional and Physical Signs

- Facial Expressions:

- Clenched jaws, tightened facial muscles, or staring intensely at staff members can indicate the buildup of aggressive impulses.

- 2 Heightened Anxiety or Irritability:

- Individuals may exhibit signs of severe irritability, including rapid, disjointed speech or hyperactivity.

2.4. Assessing the Potential for Aggression or Violence

A structured approach is essential to assess an individual’s risk of violence. Nurses should use both subjective and objective measures, combining patient history, current symptoms, and behavioral observations.

2.4.1. The HCR-20 Violence Risk Assessment

The HCR-20 (Historical, Clinical, Risk Management) is a validated tool used to assess the risk of violence in psychiatric settings. The tool evaluates three domains:

- Historical Factors: Past behavior, history of violence, substance use, and childhood trauma.

- Clinical Factors: Current mental state, including symptoms of psychosis, impulsivity, or emotional instability.

- Risk Management: Environmental stressors, lack of social support, and access to means of violence.

2.4.2. Assessing Immediacy of Risk

Nurses should determine how imminent the risk of violence is by asking the following:

- Has the patient made specific threats against others?

- Are there weapons or other means of violence readily accessible?

- Is the patient showing signs of escalating agitation or distress?

2.5. Interventions for Managing Aggression and Violence Risk

Effective interventions for aggression involve a combination of prevention, de-escalation techniques, and treatment of underlying psychiatric conditions.

2.5.1. De-Escalation Techniques

- Verbal De-Escalation:

- Nurses should use calm, non-confrontational language when speaking with aggressive patients. Offering the patient space to express their frustrations without provoking confrontation is key.

- Environmental Modifications:

- Reducing noise, dimming lights, or offering the patient a private space can help de-escalate a potentially violent situation.

- Physical Restraints (as a last resort):

- Physical restraints should only be used when there is an immediate danger to the patient or others and when other de-escalation measures have failed.

2.5.2. Long-Term Management

- Pharmacological Interventions:

- Antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and mood stabilizers can be used to control aggression in the long term. Rapid tranquilization may be necessary for acute episodes of violence.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT):

- CBT can help individuals recognize and manage triggers for aggression, teaching coping strategies to prevent violent outbursts.

Conclusion

The mental health assessment of individuals at risk for self-harm, suicide, or aggression is a multifaceted and vital responsibility for nurses. Identifying risk factors, recognizing warning signs, and effectively assessing the intent of individuals at risk can prevent tragedies and promote safety in psychiatric settings. Interventions must be tailored to address both the immediate safety concerns and the long-term needs of the patient. In-depth understanding and proper implementation of these risk assessment strategies are essential components of effective psychiatric care.

Functional Assessment

Introduction

A functional assessment is an essential component of a comprehensive mental health evaluation. It examines how an individual’s mental health condition affects their ability to perform daily living activities, cope with stress, and engage in meaningful work, social, and leisure activities. For psychiatric nurses, understanding these aspects is critical for developing effective care plans that address the patient’s psychological, emotional, and social well-being.

The two core areas of a functional assessment in psychiatric nursing are Daily Living Skills and Coping Mechanisms. These areas provide valuable insights into how mental health challenges impact an individual’s self-care abilities and their capacity to manage stress and mental health issues. This chapter offers an in-depth exploration of each area, emphasizing detailed assessment strategies, contributing factors, and intervention techniques that help improve the quality of life for individuals with mental health concerns.

-

Functional Assessment: Daily Living Skills

1.1. Definition and Importance

Daily living skills refer to the basic activities that individuals need to perform to maintain personal care, manage their household, work, and engage in social activities. A thorough assessment of these skills provides insight into the level of independence or dependency an individual might have due to their mental health condition.

These skills fall into two broad categories:

- Basic Activities of Daily Living (ADLs): These include personal hygiene, grooming, feeding, toileting, and mobility.

- Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs): These are more complex activities required to live independently, such as managing finances, shopping, preparing meals, and handling transportation.

Assessing daily living skills in psychiatric settings is crucial because mental health conditions often impair cognitive and emotional functioning, leading to difficulties in performing even basic self-care tasks. Psychiatric nurses must understand the extent of impairment to tailor their care plans and ensure that patients receive the appropriate interventions.

1.2. Impact of Mental Health on Self-Care

Mental health disorders, such as depression, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, and bipolar disorder, can significantly affect an individual’s ability to maintain personal hygiene, manage their health, and perform other essential tasks.

1.2.1. Depression and Daily Living Skills

- Physical fatigue and lack of motivation are common in depression, often leading to neglect of basic self-care tasks like bathing, brushing teeth, or changing clothes.

- Cognitive impairments, such as poor concentration and memory, can make it challenging for individuals to plan or organize their day-to-day activities.

- Depression often leads to social withdrawal, resulting in difficulties maintaining relationships and participating in social activities, further exacerbating feelings of isolation.

1.2.2. Schizophrenia and Daily Living Skills

- Individuals with schizophrenia may experience disorganized thinking and behavior, which can disrupt their ability to perform routine tasks, such as preparing meals, managing finances, or maintaining hygiene.

- Negative symptoms, such as anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure) and avolition (lack of motivation), often result in poor self-care.

- In some cases, individuals may exhibit bizarre or inappropriate behaviors, such as wearing clothing unsuitable for the weather or neglecting personal hygiene.

1.2.3. Anxiety Disorders and Daily Living Skills

- People with severe anxiety may find it difficult to leave the house, engage in social activities, or complete tasks that require attention and focus.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), a type of anxiety disorder, can interfere with daily living due to the excessive time spent on rituals, such as hand washing, cleaning, or checking, which hinders the completion of other important tasks.

1.2.4. Bipolar Disorder and Daily Living Skills

- During manic episodes, individuals may engage in risky or impulsive behaviors, such as spending excessive amounts of money or making poor financial decisions, which impacts their ability to manage daily responsibilities.

- Conversely, during depressive episodes, individuals with bipolar disorder may experience a significant decline in energy and motivation, making it difficult to maintain a regular routine.

1.3. Assessing Daily Living Skills

A comprehensive assessment of daily living skills involves gathering information about the patient’s current functioning across various domains, including self-care, household management, work, and social interactions. This process typically includes the following steps:

1.3.1. Observation

- Psychiatric nurses should observe the patient’s ability to perform basic tasks such as grooming, eating, and dressing. Non-verbal cues such as poor hygiene, unkempt appearance, or lack of energy provide critical insights into their functional abilities.

1.3.2. Interviews with Patients and Caregivers

- Conducting interviews allows nurses to understand the patient’s perception of their ability to manage daily activities. Asking specific questions about how they manage routine tasks, their difficulties, and how their mental health condition affects their functioning can yield important data.

- Interviews with family members or caregivers also provide an objective assessment of the patient’s daily functioning, especially if the patient minimizes or is unaware of the extent of their impairments.

1.3.3. Standardized Tools for Assessing ADLs and IADLs

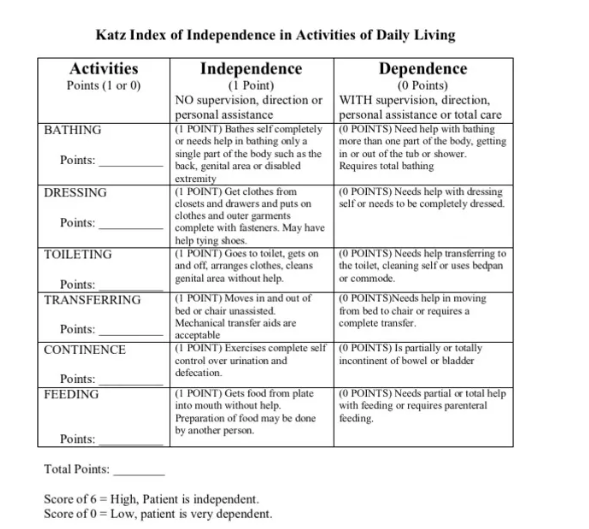

- The Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living:

This tool assesses the patient’s ability to perform six basic functions: bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence, and feeding.

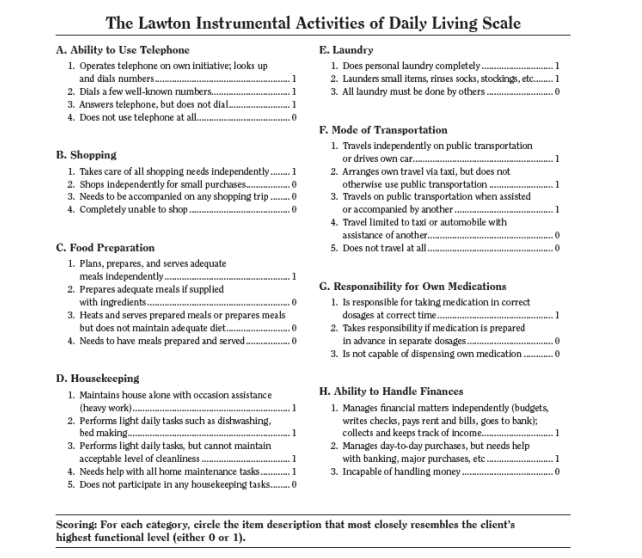

- Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale:

This tool evaluates more complex daily tasks such as using the phone, shopping, preparing meals, housekeeping, and managing finances.

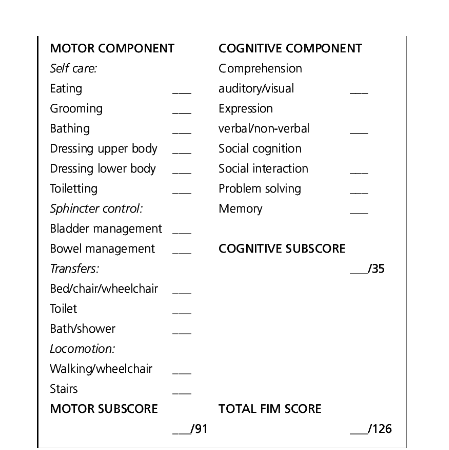

- Functional Independence Measure (FIM):

Often used in rehabilitation settings, this tool assesses both motor and cognitive tasks related to daily functioning.

1.4. Common Challenges in Daily Living Skills

Mental health disorders often present unique challenges that make daily tasks overwhelming. Some common issues include:

1.4.1. Cognitive Impairments

- Mental health conditions such as schizophrenia, major depression, or anxiety can impair cognitive functioning, making it difficult for individuals to remember tasks, organize their day, or make decisions.

1.4.2. Physical Limitations

- Some psychiatric medications cause side effects such as lethargy, sedation, or motor difficulties, which can further impair the individual’s ability to perform daily activities.

1.4.3. Lack of Social Support

- Individuals without adequate social support often struggle to maintain self-care or household responsibilities. For example, someone living alone may find it difficult to manage grocery shopping, meal preparation, or household chores, which could exacerbate feelings of isolation and helplessness.

1.4.4. Medication Adherence Issues

- Many patients with mental health conditions struggle with medication adherence, either due to cognitive impairments, denial of their illness, or side effects of the medication. Non-adherence can lead to a deterioration in functioning, which affects daily living skills.

1.5. Interventions to Improve Daily Living Skills

To enhance the quality of life for individuals with mental health conditions, psychiatric nurses must employ targeted interventions aimed at improving daily living skills. These interventions may include:

1.5.1. Psychoeducation

- Teaching patients about their condition, the importance of self-care, and how to manage their symptoms can empower them to take an active role in their recovery.

- Medication management education is essential, particularly for patients with cognitive impairments, as it improves adherence and reduces the likelihood of functional decline.

1.5.2. Occupational Therapy

- Occupational therapists work closely with patients to help them develop or regain the skills necessary for daily living. This may include training in cooking, budgeting, personal hygiene, or other instrumental activities.

1.5.3. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

- CBT can help patients identify negative thought patterns that contribute to functional decline. By teaching coping strategies and problem-solving skills, CBT can improve daily functioning.

1.5.4. Social Support Services

- Linking patients with social workers or community resources can help ensure they have access to housing, financial assistance, and social support networks that contribute to functional independence.

1.5.5. Structured Routine Development

- Encouraging patients to follow a structured daily routine can improve organization and reduce cognitive overload. This may involve the use of calendars, reminders, or checklists to ensure tasks are completed.

-

Functional Assessment: Coping Mechanisms

2.1. Definition and Importance

Coping mechanisms are the strategies individuals use to manage stress, anxiety, and emotional challenges. In mental health nursing, understanding a patient’s coping mechanisms is essential because these strategies determine how well they can handle their illness and the daily stressors that arise from it.

Coping mechanisms can be adaptive (healthy) or maladaptive (unhealthy), and psychiatric nurses must assess both to develop effective interventions. An individual’s ability to cope can affect not only their mental health outcomes but also their physical health, relationships, and overall well-being.

2.2. Types of Coping Mechanisms

Coping mechanisms are typically divided into two broad categories: adaptive (healthy) and maladaptive (unhealthy).

Communication

Therapeutic communication is a vital skill in psychiatric nursing. It is the purposeful and goal-oriented interaction between the nurse and the patient, which focuses on improving the patient’s well-being and fostering a trusting relationship. Therapeutic communication involves both verbal and nonverbal techniques and requires the nurse to be mindful of their approach, tone, and body language. It also demands that nurses understand the complexities of human emotions and provide support, empathy, and validation in a professional manner.

This chapter provides an in-depth exploration of therapeutic communication techniques such as active listening, empathy and support, and nonverbal communication. Each section will delve into the specific skills, strategies, and underlying theories that make these techniques effective in promoting the therapeutic alliance and enhancing patient outcomes.

-

Communication Techniques in Therapeutic Communication

1.1. Active Listening

Active listening is a foundational communication skill in psychiatric nursing. It involves not only hearing the patient’s words but also paying close attention to the underlying emotions, thoughts, and concerns that may not be immediately apparent. Active listening helps nurses understand the patient’s perspective and fosters a safe and supportive environment in which the patient feels heard and validated.

Active listening comprises several components, including reflective listening, summarizing, and clarifying. These techniques allow nurses to engage with patients in a meaningful way and to ensure that communication is clear, supportive, and focused on the patient’s needs.

1.1.1. Reflective Listening

Reflective listening involves restating or paraphrasing what the patient has said in order to confirm understanding and demonstrate that the nurse is truly engaged. This technique helps the patient feel heard and encourages them to elaborate on their thoughts and feelings. Reflective listening also provides the nurse with an opportunity to explore the emotional undertones of what the patient is saying.

For example:

- Patient: “I don’t know why I even bother taking my medication. Nothing ever seems to change.”

- Nurse: “It sounds like you’re feeling frustrated and discouraged about your treatment.”

By reflecting the patient’s words and emotions, the nurse helps the patient feel validated and opens the door to further exploration of the issue.

1.1.2. Summarizing

Summarizing involves briefly restating the key points of what the patient has shared during a conversation. This technique is useful for ensuring clarity, organizing thoughts, and helping the patient feel understood. Summarizing is particularly helpful at the end of a session or conversation, as it allows both the nurse and the patient to review important issues that were discussed and to set priorities for future sessions.

For example:

- Nurse: “To summarize, it seems like you’re struggling with feelings of hopelessness about your recovery, you’re finding it difficult to stay motivated with your treatment, and you’re worried about your future.”

Summarizing helps the nurse confirm that they have correctly understood the patient’s concerns, and it provides an opportunity to clarify any misunderstandings before moving forward.

1.1.3. Clarifying

Clarifying is a technique used to ask for more information or to seek clarification about something the patient has said. This is particularly important when the patient’s statements are vague, confusing, or contradictory. By asking the patient to clarify their thoughts, the nurse demonstrates interest and helps the patient explore their emotions in greater depth.

For example:

- Nurse: “When you say you feel ‘empty,’ can you help me understand what that means for you?”

Clarifying encourages the patient to reflect on their feelings and provides the nurse with a clearer understanding of the patient’s emotional state. It is a powerful tool in deepening the therapeutic conversation and gaining insight into the patient’s internal experiences.

1.2. Empathy and Support

Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another person. In psychiatric nursing, empathy is crucial for building trust and rapport with patients. It allows nurses to connect with patients on an emotional level and to validate their experiences. Unlike sympathy, which may involve feeling sorry for the patient, empathy requires the nurse to enter into the patient’s world and acknowledge their emotions without judgment.

Supporting patients through empathetic communication helps them feel less isolated in their struggles and more capable of coping with their challenges. This support is crucial in psychiatric settings, where patients often experience significant emotional distress, confusion, and vulnerability.

1.2.1. Showing Empathy

Empathy in communication can be expressed both verbally and nonverbally. Verbal expressions of empathy involve acknowledging the patient’s emotions and demonstrating that the nurse understands their feelings.

For example:

- Patient: “I just feel like no one understands how hard this is for me.”

- Nurse: “It sounds like you’re feeling really alone in this, and that must be incredibly difficult for you.”

By validating the patient’s emotions, the nurse shows that they are attuned to the patient’s experience. This fosters a sense of safety and trust, allowing the patient to open up more fully about their feelings.

Nonverbal expressions of empathy include maintaining appropriate eye contact, using gentle and reassuring facial expressions, and adopting a calm and open body posture. These cues reinforce the message that the nurse is present and attentive to the patient’s emotional needs.

1.2.2. Providing Emotional Support

In psychiatric nursing, providing emotional support involves offering reassurance, encouragement, and validation to help patients cope with their feelings. This can be especially important for individuals who are experiencing intense emotions such as anxiety, fear, sadness, or anger.

Supportive communication often includes statements that convey understanding and offer hope, without minimizing the patient’s struggles.

For example:

- Nurse: “I can see that you’re feeling overwhelmed right now. Let’s take this one step at a time, and we’ll work through it together.”

Supportive communication also involves being present and available for the patient. Sometimes, simply sitting with the patient and offering a compassionate presence can provide immense comfort.

1.2.3. Balancing Empathy with Professional Boundaries

While empathy is essential, psychiatric nurses must also maintain professional boundaries to ensure that they do not become emotionally overwhelmed or enmeshed in the patient’s struggles. Maintaining appropriate boundaries ensures that the nurse can remain objective and provide the best possible care.

Balancing empathy with boundaries involves:

- Avoiding over-identification with the patient’s problems.

- Recognizing when to refer the patient to other professionals for additional support (e.g., a psychologist or social worker).

- Setting limits on personal disclosure, ensuring that the focus remains on the patient.

Effective therapeutic communication requires the nurse to be compassionate and empathetic, while also protecting their own emotional well-being and maintaining professional detachment when necessary.

- Nonverbal Communication in Therapeutic Communication

Nonverbal communication is just as important as verbal communication in therapeutic interactions. In fact, research suggests that a significant portion of communication is nonverbal, and patients often pick up on cues from body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice. Understanding and using nonverbal communication effectively is essential for psychiatric nurses as it can enhance or undermine the therapeutic relationship.

Nonverbal communication includes:

- Body language: Gestures, posture, and physical proximity.

- Facial expressions: Smiles, frowns, raised eyebrows, and other expressions that convey emotion.

- Eye contact: The level of engagement or avoidance in visual connection.

- Paralanguage: Tone, pitch, and speed of speech, which influence how the message is perceived.

2.1. Using Body Language Effectively

Body language is a powerful tool in therapeutic communication. The way a nurse positions their body can either invite a patient to engage or make them feel uncomfortable or judged. Open, relaxed body language conveys a message of warmth and acceptance, whereas closed or tense body language can create a barrier to communication.

2.1.1. Open Posture

- An open posture, such as sitting facing the patient with uncrossed arms and legs, indicates that the nurse is approachable and ready to listen. Leaning slightly forward shows engagement and interest in what the patient is saying.

2.1.2. Closed Posture

- A closed posture, such as crossing arms, turning away, or leaning back, can signal disinterest, discomfort, or defensiveness. This type of body language may cause the patient to feel rejected or misunderstood.

2.1.3. Personal Space

- Maintaining an appropriate physical distance is important in psychiatric settings. While it’s essential to be close enough to engage the patient, being too close can invade their personal space and make them feel uncomfortable. The appropriate distance may vary depending on cultural norms and the patient’s comfort level, but generally, sitting about an arm’s length away is considered respectful.

2.2. Eye Contact

Eye contact is a critical aspect of nonverbal communication in psychiatric nursing. Appropriate eye contact helps convey attentiveness, interest, and empathy, while avoiding eye contact can suggest disinterest, discomfort, or even dishonesty.

2.2.1. Engaging with Eye Contact

- Maintaining consistent but not intense eye contact communicates that the nurse is present and focused on the patient. It signals that the nurse is paying attention and values what the patient has to say.

2.2.2. Avoiding Excessive Eye Contact

- While eye contact is important, staring or maintaining unbroken eye contact can feel confrontational or uncomfortable for some patients, particularly those with anxiety or trauma histories. The nurse should balance eye contact with occasional breaks to allow the patient to feel at ease.

2.3. Facial Expressions

Facial expressions often provide insight into the nurse’s emotional reactions to what the patient is saying. A neutral, calm, and compassionate expression can help the patient feel supported, while an expression of shock, disapproval, or impatience may make the patient feel judged or misunderstood.

2.3.1. Empathetic Facial Expressions

- A gentle smile, raised eyebrows (indicating curiosity or concern), and a relaxed face can communicate empathy and openness. These expressions encourage the patient to continue sharing and help foster a sense of connection.

2.3.2. Avoiding Negative Expressions

- Negative expressions, such as frowns, eye-rolling, or grimaces, can damage the therapeutic relationship. Even subtle expressions of frustration or disbelief may make the patient feel invalidated and less likely to engage in further conversation.

2.4. Paralanguage

Paralanguage refers to the nonverbal elements of speech, such as tone, pitch, and pacing. In therapeutic communication, the way something is said can be just as important as the words themselves.

2.4.1. Tone of Voice

- A calm, soothing tone conveys patience and understanding, helping the patient feel comfortable and secure. An abrupt or harsh tone, on the other hand, may cause the patient to feel threatened or dismissed.

2.4.2. Pacing and Speed of Speech

- Speaking too quickly can overwhelm the patient, especially if they are experiencing cognitive difficulties, anxiety, or confusion. Slower, measured speech gives the patient time to process information and respond at their own pace.

2.4.3. Volume

- The volume of speech is also significant. Speaking too loudly may come across as aggressive or intimidating, while speaking too softly may suggest lack of confidence or uncertainty. A moderate volume, appropriate to the setting and patient’s needs, is typically ideal.

-

Advanced Therapeutic Communication Techniques

3.1. Validation Therapy

Validation therapy is a communication strategy that focuses on acknowledging and validating the patient’s emotions and perceptions, even when they may not align with reality. This technique is particularly useful when working with patients who have dementia or other cognitive impairments, as it helps reduce anxiety and distress.

3.1.1. The Principles of Validation Therapy

- In validation therapy, the nurse does not attempt to correct or challenge the patient’s perceptions. Instead, the nurse acknowledges the patient’s feelings and provides reassurance.

Example:

- Patient: “I need to get home; my children will be waiting for me.”

- Nurse: “It sounds like you’re worried about your children. Tell me more about them.”

By validating the patient’s emotions, the nurse helps the patient feel heard and respected, even if their thoughts are based on a distorted reality.

3.2. Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a patient-centered communication technique that helps patients explore and resolve ambivalence about making changes in their lives. MI is particularly effective in working with patients who may be struggling with substance use disorders, lifestyle changes, or adherence to treatment plans.

3.2.1. The Principles of Motivational Interviewing

- MI is based on four key principles:

- Express empathy: Use reflective listening to understand the patient’s perspective.

- Develop discrepancy: Help the patient recognize the gap between their current behaviors and their goals.

- Roll with resistance: Avoid confrontation and allow the patient to explore their own reasons for change.

- Support self-efficacy: Encourage the patient to believe in their ability to make positive changes.

Example:

- Nurse: “It sounds like part of you wants to quit smoking, but another part is worried about how hard it will be. Let’s talk more about what’s making it difficult for you to make that change.”

Motivational interviewing helps the patient resolve ambivalence and move toward healthier behaviors in a non-judgmental, supportive way.

- The Therapeutic Alliance and Its Impact on Patient Outcomes

The therapeutic alliance is the collaborative, trusting relationship between the nurse and the patient. A strong therapeutic alliance is built on open communication, empathy, mutual respect, and shared goals. Research has consistently shown that the quality of the therapeutic alliance is one of the most important predictors of positive patient outcomes in psychiatric care.

4.1. Building Trust in the Therapeutic Relationship

- Trust is essential in therapeutic communication. When patients trust their nurse, they are more likely to share personal information, adhere to treatment plans, and engage in the therapeutic process.

4.2. Maintaining Boundaries in the Therapeutic Alliance

- While building a trusting relationship is crucial, it’s also important to maintain professional boundaries. Overstepping boundaries can lead to dependency or blurred roles, which can harm both the patient and the nurse.

Conclusion

Therapeutic communication is a critical component of psychiatric nursing, encompassing a wide range of skills and techniques aimed at improving patient outcomes and fostering a positive therapeutic relationship. From active listening and empathy to nonverbal communication and advanced strategies like motivational interviewing, these techniques enable nurses to connect with patients on a deeper level, support their emotional needs, and guide them toward recovery.

Therapeutic Communication: Building Rapport

Therapeutic communication is a core component of psychiatric nursing. Building rapport with patients is the cornerstone of this type of communication and directly impacts the quality of care, patient engagement, and overall outcomes in psychiatric settings. The ability to establish trust and respect while maintaining professional boundaries is essential for creating a safe and supportive environment where patients feel comfortable opening up about their feelings, thoughts, and experiences. This section delves into the key elements of building rapport, focusing on trust and respect, boundaries, and confidentiality.

- Building Rapport in Psychiatric Nursing

Building rapport refers to the process of creating a positive, trusting, and respectful relationship between the nurse and the patient. In psychiatric nursing, rapport is not only necessary for effective communication but is also crucial for the patient’s mental health recovery. Establishing a strong rapport helps patients feel understood and valued, which can lower their defenses, reduce feelings of isolation, and promote emotional and psychological healing.

1.1. The Importance of Rapport in Therapeutic Communication

- Trust: Patients must trust that the nurse has their best interests at heart, which enables open and honest communication.

- Respect: Patients, especially those in psychiatric care, often feel vulnerable and misunderstood. Respecting their feelings, thoughts, and autonomy fosters a supportive environment.

- Empathy: The ability to empathize with patients—seeing the world through their eyes—enhances the therapeutic alliance and strengthens the nurse-patient relationship.

- Mutual Understanding: A rapport built on mutual understanding can break down the emotional and psychological barriers that often arise in psychiatric care, allowing for more effective interventions.

-

Trust and Respect: Establishing a Therapeutic Relationship

A therapeutic relationship is a professional alliance in which the nurse collaborates with the patient to promote their emotional, psychological, and physical well-being. In psychiatric nursing, this relationship is built on the foundations of trust and respect. Without these two critical components, patients are unlikely to engage fully in their treatment, express their true feelings, or comply with their care plan.

2.1. Trust: The Foundation of Therapeutic Relationships

Trust is the foundation upon which therapeutic relationships are built. In psychiatric care, trust is essential because patients often come from environments where they have experienced trauma, stigma, or a lack of understanding. Without trust, patients are less likely to share personal information or participate in their treatment plans, which can hinder recovery.

2.1.1. Building Trust

- Consistency: Consistent behavior from the nurse helps establish predictability, which is crucial for patients dealing with mental health challenges. When nurses follow through on their promises, patients are more likely to trust them.

- Honesty: Being open and transparent with patients is critical for building trust. Nurses should be honest about the treatment process, potential outcomes, and the challenges ahead.

- Active Listening: Actively listening to patients and giving them your undivided attention shows that you value their experiences and feelings. This, in turn, helps build trust.

- Non-Judgmental Attitude: Psychiatric patients may have fears of being judged, especially if their thoughts or behaviors deviate from societal norms. Nurses must practice non-judgmental communication to foster trust.

- Reliability: Consistently being there for patients, responding to their needs in a timely manner, and showing that you care helps establish the nurse as a reliable and trusted figure in the patient’s care.

2.1.2. Maintaining Trust Over Time

- Follow-through: Trust can be broken if the nurse makes promises they do not keep. It’s essential to manage expectations and follow through with commitments, even small ones.

- Setting Realistic Expectations: Patients in psychiatric settings may have unrealistic expectations regarding their recovery. Nurses need to communicate realistic goals to avoid breaking trust.

- Handling Mistakes: Nurses are not infallible. If a mistake occurs, acknowledging it and discussing it with the patient openly is key to maintaining trust. Covering up errors or failing to address issues can damage the therapeutic relationship.

2.2. Respect: Fostering Dignity and Autonomy in Psychiatric Nursing

Respecting the patient’s dignity, autonomy, and individuality is fundamental to psychiatric nursing. Patients in psychiatric care often feel marginalized and powerless, so it is critical that nurses respect their rights and personal space.

2.2.1. Demonstrating Respect

- Acknowledging Individuality: Every patient is unique, with their own set of experiences, beliefs, and values. Acknowledging and respecting these individual differences is crucial in psychiatric care.

- Promoting Autonomy: Psychiatric patients often feel a loss of control over their lives. By involving them in decision-making processes and respecting their choices, nurses can help restore a sense of autonomy.

- Respecting Cultural Differences: Cultural competence is essential in psychiatric nursing. Nurses must respect the patient’s cultural background and integrate it into their care approach. This includes understanding cultural perceptions of mental health, treatment preferences, and communication styles.

- Respectful Language: The words used when speaking to or about psychiatric patients can either build them up or break them down. Nurses should use language that promotes dignity and respect, avoiding terms that stigmatize or label the patient.

2.2.2. Respecting Boundaries

- Privacy and Confidentiality: Respecting the patient’s right to privacy is a form of respect that is especially important in psychiatric settings. Confidentiality must be maintained to protect the patient’s personal information and ensure their trust.

- Emotional Boundaries: Patients in psychiatric care may share deeply personal and emotional experiences. Nurses must listen and empathize while maintaining professional boundaries to avoid becoming over-involved emotionally.

2.2.3. The Role of Empathy in Respect

- Empathy and Respect: Empathy goes hand in hand with respect. When a nurse demonstrates empathy, they validate the patient’s feelings and experiences, which fosters mutual respect. By walking in the patient’s shoes, nurses show that they understand and respect the patient’s emotional world.

- Avoiding Paternalism: While empathy is essential, it’s important to avoid paternalism. This occurs when nurses assume they know what’s best for the patient without involving the patient in the decision-making process. Respect means recognizing the patient’s ability to make informed choices about their care.

-

Boundaries: Maintaining Professional Boundaries and Confidentiality

Boundaries are essential in psychiatric nursing to ensure the therapeutic relationship remains professional and focused on the patient’s well-being. Maintaining boundaries helps protect both the nurse and the patient from harm, prevents dependency, and ensures that the care provided is ethical and effective.

3.1. Understanding Professional Boundaries in Psychiatric Care

Professional boundaries define the limits of the relationship between the nurse and the patient. They help delineate what is appropriate in terms of physical, emotional, and social interactions. In psychiatric care, where patients are often vulnerable and emotionally fragile, maintaining these boundaries is even more critical.

3.1.1. The Importance of Boundaries

- Preventing Dependency: Patients in psychiatric care may become overly reliant on their nurse for emotional support. While it’s important to provide care and empathy, crossing boundaries can foster an unhealthy dependency.

- Avoiding Role Confusion: The nurse’s role is to provide care and support, not to be a friend or confidant in a personal sense. Role confusion can arise if boundaries are not clearly defined and maintained, which may lead to misunderstandings or inappropriate behavior.

- Ensuring Objectivity: Maintaining professional boundaries allows the nurse to remain objective and provide unbiased care. When boundaries are blurred, the nurse may struggle to make impartial decisions that are in the patient’s best interest.

3.1.2. Common Boundary Violations

- Over-involvement: Becoming too emotionally involved in the patient’s life or sharing personal information that is not relevant to the patient’s care can constitute a boundary violation.

- Physical Contact: While therapeutic touch may be appropriate in certain situations, it must always be done with consent and awareness of the patient’s comfort level. Physical contact should never be excessive or cross professional lines.

- Dual Relationships: A dual relationship occurs when the nurse has a personal or social relationship with the patient outside of the therapeutic context. This can lead to conflicts of interest and should be avoided.

3.1.3. Strategies for Maintaining Boundaries

- Self-awareness: Nurses must be aware of their own emotional needs and triggers to avoid becoming overly involved with patients. Reflective practice and supervision can help nurses maintain professional boundaries.

- Clear Communication: Setting clear expectations with patients about the nature of the therapeutic relationship is essential. Patients should understand that the nurse’s role is to provide care and support, but that personal involvement is limited to professional interactions.

- Time Management: Spending an appropriate amount of time with each patient is important for maintaining boundaries. While it’s crucial to provide enough time for therapeutic interaction, overextending time with a particular patient can blur boundaries.

3.2. Confidentiality: Protecting Patient Privacy

Confidentiality is a cornerstone of psychiatric nursing and is crucial for building trust in the therapeutic relationship. Psychiatric patients often share deeply personal and sensitive information, and they must feel confident that this information will be protected. Breaches of confidentiality can damage trust and have serious legal and ethical consequences.

3.2.1. Legal and Ethical Considerations

- HIPAA: In the United States, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) mandates the protection of patient information. Nurses must adhere to HIPAA regulations to ensure that patient information is kept private.

- Informed Consent: Patients must be informed about the limits of confidentiality. In psychiatric nursing, certain situations (such as imminent harm to self or others) may require breaking confidentiality, and patients should be made aware of this.

- Mandatory Reporting: While confidentiality is critical, nurses are also required to report certain situations, such as abuse or threats of harm. Patients should be informed of these exceptions to confidentiality.

3.2.2. Strategies for Maintaining Confidentiality

- Secure Records: Patient records should be kept secure, and access should be limited to those directly involved in the patient’s care. Digital records must be password-protected and comply with security standards.

- Private Conversations: Therapeutic conversations should take place in private settings where others cannot overhear sensitive information. Ensuring patient confidentiality during discussions is essential for protecting their privacy.

- Discretion in Public Settings: In psychiatric settings, patients may encounter nurses in public spaces. Nurses must exercise discretion and avoid discussing patient information in these environments.

3.3. The Impact of Boundaries and Confidentiality on Therapeutic Communication

Maintaining professional boundaries and confidentiality directly impacts the effectiveness of therapeutic communication. When patients feel that their privacy is respected and that the nurse is maintaining appropriate professional boundaries, they are more likely to engage in meaningful communication. Conversely, boundary violations or breaches of confidentiality can erode trust and undermine the therapeutic relationship.

Conclusion

Building rapport through trust, respect, and clear professional boundaries is essential in psychiatric nursing. These elements foster a safe, supportive environment where patients feel comfortable sharing their thoughts, feelings, and experiences. By maintaining confidentiality, demonstrating empathy, and upholding professional boundaries, nurses can establish therapeutic relationships that promote emotional and psychological healing. The skills and principles outlined in this chapter form the foundation of effective therapeutic communication in psychiatric care and are crucial for the patient’s recovery and overall well-being.

Therapeutic Communication: Intervention Strategies