Human Anatomy and Physiology

Chapter 1: Introduction & Foundations

Overview of Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy and physiology are closely related fields that study the structure and function of the human body, respectively.

i. Anatomy is the branch of biology that focuses on the physical structure of organisms. It can be divided into:

- Gross Anatomy: The study of structures visible to the naked eye, such as organs and tissues.

- Microscopic Anatomy: The study of structures that require magnification to be seen, including histology (the study of tissues) and cytology (the study of cells).

ii. Physiology examines how the body parts function and interact. It can be categorized into:

- Cell Physiology: The study of cellular functions.

- Systemic Physiology: The study of the functions of organ systems.

- Pathophysiology: The study of disease processes and their impact on body functions.

Understanding the relationship between anatomy and physiology is crucial because the function of an organ or system is intrinsically linked to its structure. For example, the structure of the heart’s chambers and valves directly affects its ability to pump blood efficiently.

Levels of Organization in the Human Body

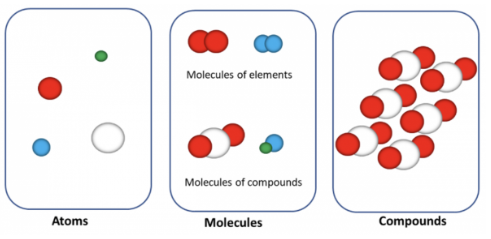

The human body is organized into several levels of complexity, each building on the previous one:

i. Chemical Level:

Includes atoms and molecules, the most basic form of matter. For instance, carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and nitrogen are fundamental elements in biological molecules such as proteins and nucleic acids.

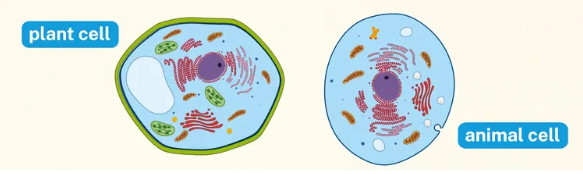

ii. Cellular Level:

Cells are the smallest living units of the body. They vary in shape and function, with each type of cell specialized for particular tasks. Examples include muscle cells for contraction and nerve cells for signal transmission.

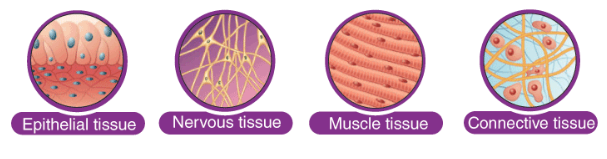

iii. Tissue Level: Tissues are groups of similar cells working together to perform specific functions. There are four basic types of tissues:

- Epithelial Tissue: Covers body surfaces and lines hollow organs. It functions in protection, absorption, and secretion.

- Connective Tissue: Supports and binds other tissues. Includes bone, blood, and adipose (fat) tissue.

- Muscle Tissue: Facilitates movement. Includes skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle tissues.

- Nervous Tissue: Transmits electrical impulses and processes information. Comprises neurons and supporting cells.

iv. Organ Level: Organs are composed of two or more tissue types working together to perform specific functions. For instance, the stomach includes all four tissue types and functions in digestion.

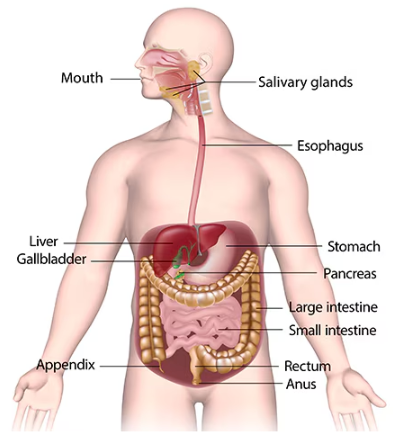

v. Organ System Level: Organ systems are groups of organs that work together to perform complex functions. Examples include the digestive system, respiratory system, and circulatory system.

vi. Organismal Level: The highest level of organization, where all systems function together to maintain life and health.

Homeostasis

Homeostasis is the process by which the body maintains a stable internal environment despite external changes. It involves feedback mechanisms that regulate variables such as temperature, pH, and glucose levels.

- Negative Feedback: The most common homeostatic mechanism, where a change in a variable triggers responses that counteract the initial change. For example, if body temperature rises, mechanisms like sweating and vasodilation work to cool the body down.

- Positive Feedback: Less common, this mechanism amplifies changes rather than counteracting them. Positive feedback is usually seen in processes such as childbirth, where the release of oxytocin increases the intensity of contractions.

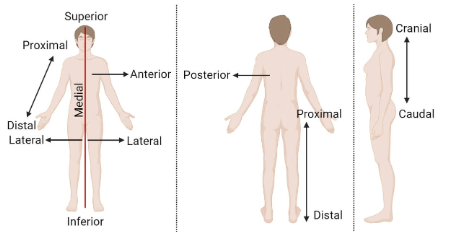

Anatomical Terminology

To accurately describe the locations and relationships of body parts, standardized anatomical terminology is used:

i. Anatomical Position: The body is standing upright, facing forward, with arms at the sides and palms facing forward. This position serves as a reference for directional terms.

ii. Directional Terms: Used to describe the location of structures relative to other structures:

- Superior/Inferior: Above or below a reference point.

- Anterior/Posterior: Front or back of the body.

- Medial/Lateral: Toward or away from the midline of the body.

- Proximal/Distal: Closer to or farther from the point of attachment or origin.

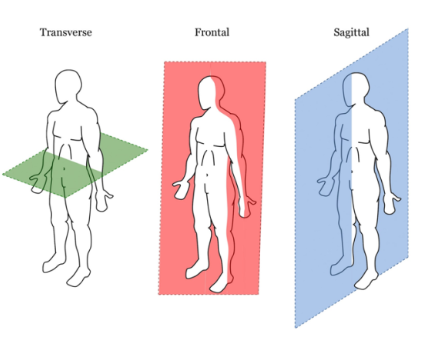

iii. Body Planes and Sections:

Imaginary lines that divide the body into sections:

- Sagittal Plane: Divides the body into left and right parts.

- Coronal (Frontal) Plane: Divides the body into anterior and posterior parts.

- Transverse Plane: Divides the body into superior and inferior parts.

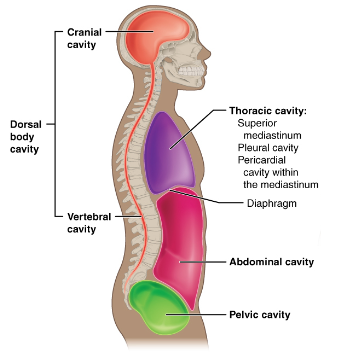

iv. Body Cavities:

Spaces within the body that house organs:

- Dorsal Cavity: Includes the cranial cavity (brain) and spinal cavity (spinal cord).

- Ventral Cavity: Includes the thoracic cavity (heart and lungs) and abdominopelvic cavity (digestive organs, reproductive organs).

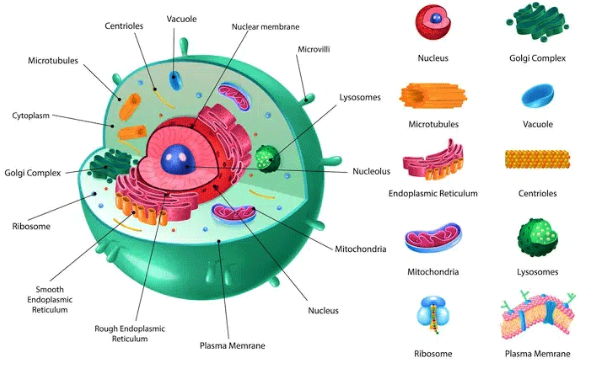

Basic Cell Structure

Cells are the fundamental units of life, and understanding their structure is crucial for comprehending their function. Key components include:

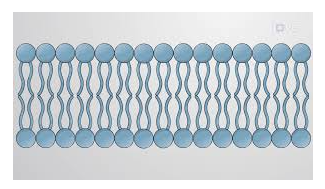

i. Plasma Membrane: A phospholipid bilayer that regulates the movement of substances in and out of the cell. It contains proteins that act as receptors and channels.

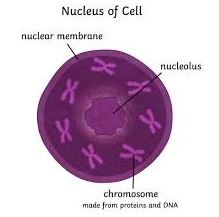

ii. Nucleus: The control center of the cell, housing DNA and coordinating activities like growth, metabolism, and reproduction.

iii. Cytoplasm: The gel-like substance between the plasma membrane and the nucleus, containing organelles and cytosol (fluid).

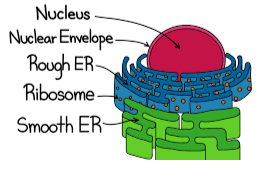

iv. Organelles: Specialized structures within the cell that perform specific functions:

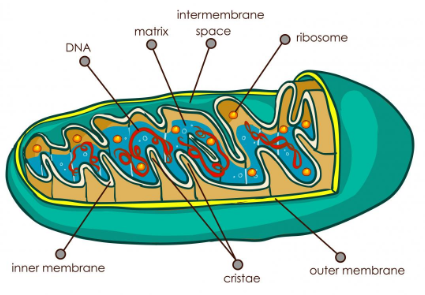

- Mitochondria: Powerhouses of the cell, generating ATP through cellular respiration.

- Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER): Rough ER is involved in protein synthesis, while smooth ER is involved in lipid synthesis and detoxification.

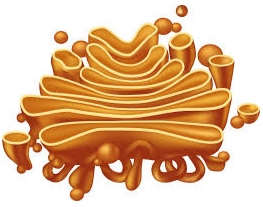

- Golgi Apparatus: Modifies, sorts, and packages proteins and lipids for secretion or internal use.

- Lysosomes: Contain digestive enzymes that break down waste materials and cellular debris.

- Ribosomes: Sites of protein synthesis.

Tissue Types and Functions

Understanding the four basic tissue types is essential for comprehending how organs and systems function:

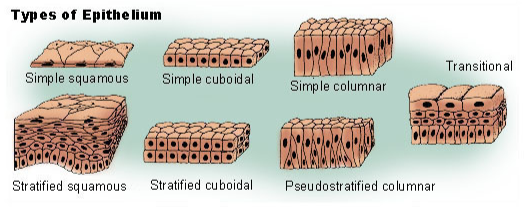

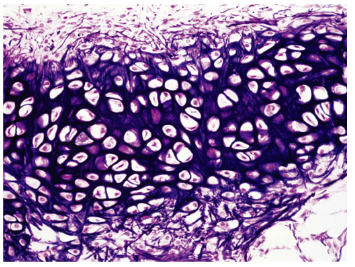

i. Epithelial Tissue: Forms protective layers and is involved in absorption, secretion, and filtration. It includes simple squamous, cuboidal, columnar, and stratified types.

ii. Connective Tissue: Provides structural and nutritional support. It includes:

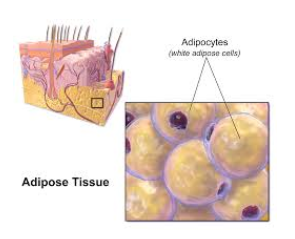

- Loose Connective Tissue: Such as adipose tissue.

- Dense Connective Tissue: Such as tendons and ligaments.

- Cartilage: Provides flexible support in areas like the nose and ears.

- Bone: Provides rigid support and protection for vital organs.

- Blood: Transports nutrients, gases, and waste products.

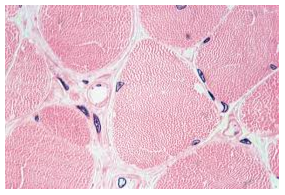

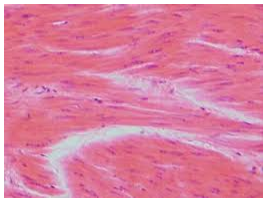

iii. Muscle Tissue: Facilitates movement. Includes:

- Skeletal Muscle: Voluntary control, striated appearance.

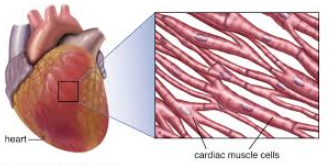

- Cardiac Muscle: Involuntary control, found in the heart, striated.

- Smooth Muscle: Involuntary control, non-striated, found in walls of organs like the intestines.

iv. Nervous Tissue: Transmits electrical impulses and processes information. Includes neurons and glial cells (supporting cells).

Integration of Systems

All body systems work in concert to maintain homeostasis and support life processes. For instance:

- The nervous system communicates with the muscular system to coordinate voluntary movements.

- The endocrine system releases hormones that regulate various physiological processes, including metabolism and growth.

- The circulatory system delivers nutrients and oxygen to tissues while removing waste products.

Homeostasis and Disease

Disruption of homeostasis can lead to diseases and disorders. Understanding the mechanisms that maintain homeostasis helps in diagnosing and treating various conditions. For example:

- Diabetes Mellitus: A condition where the body’s ability to regulate blood glucose levels is impaired.

- Hypertension: High blood pressure that can result from the body’s inability to regulate blood vessel constriction and blood volume.

Chapter 2: Cellular and Tissue Levels

Cellular and Tissue Levels

This chapter delves into the building blocks of life – cells – and how they come together to form complex tissues. We’ll explore the intricate structure and function of cells, mechanisms of transport across the cell membrane, cell division processes, and the four major tissue types that make up the human body.

Cell Structure and Function

Cells are the basic units of structure and function in living organisms. They come in various shapes and sizes, each specialized for a particular task. Here’s a breakdown of the key components of a cell and their functions:

- Cell Membrane (Plasma Membrane):

A phospholipid bilayer that forms the outer boundary of the cell. It controls what enters and leaves the cell, acting as a selective barrier.

- Cytoplasm: The jelly-like substance inside the cell membrane, containing organelles and cellular components.

- Nucleus:

The control center of the cell, containing genetic information (DNA) in the form of chromosomes. The nucleus directs protein synthesis through RNA (ribonucleic acid).

- Nucleolus: A dense region within the nucleus that produces ribosomes, essential for protein synthesis.

- Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER):

A network of membranes that manufactures, processes, and transports proteins and other molecules. There are two types: Rough ER (studded with ribosomes) and Smooth ER (lacks ribosomes and has various functions like lipid synthesis).

- Ribosomes: Cellular machines responsible for protein synthesis by translating instructions from RNA.

- Golgi Apparatus:

A flattened sac-like organelle that modifies, packages, and distributes proteins and other molecules synthesized by the ER. It acts like a cellular shipping center.

- Lysosomes: Sac-like organelles containing digestive enzymes that break down waste products, worn-out cell parts, and foreign invaders. They are the cell’s cleanup crew.

- Mitochondria:

The powerhouses of the cell, responsible for cellular respiration, the process by which energy is produced from glucose and oxygen.

- Cytoskeleton: A network of protein fibers that provides structural support, maintains cell shape, and aids in cell movement and division.

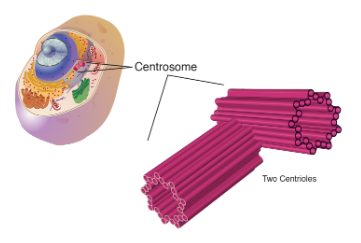

- Centrosome:

An organelle near the nucleus that plays a vital role in cell division by organizing microtubules.

Cell Membrane Transport

The cell membrane is a dynamic structure that regulates the movement of materials into and out of the cell. Different mechanisms facilitate this transport:

i. Passive Transport: Movement of substances across the membrane without the need for cellular energy (ATP). It occurs down a concentration gradient, from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration. There are three main types of passive transport:

- Diffusion: Small, uncharged molecules like oxygen and carbon dioxide can move directly through the phospholipid bilayer.

- Facilitated Diffusion: Larger molecules or charged ions require protein channels or carrier proteins in the membrane to facilitate their passage.

- Osmosis: The movement of water across a semipermeable membrane (like the cell membrane) from an area of low solute concentration (high water concentration) to an area of high solute concentration (low water concentration).This is crucial for maintaining cell volume and function.

ii. Active Transport: Movement of substances across the membrane against a concentration gradient, requiring cellular energy (ATP). Carrier proteins utilize energy to pump molecules across the membrane. This is essential for transporting essential nutrients and expelling waste products.

Mitosis and Meiosis

Cell division is vital for growth, repair, and replacement of tissues in the body. There are two main types of cell division:

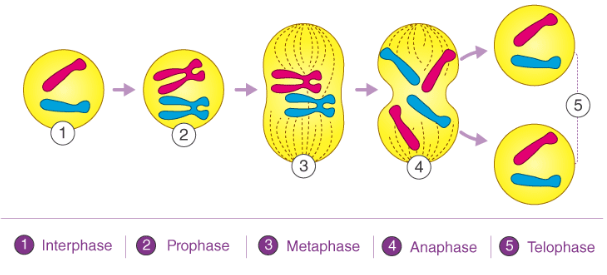

i. Mitosis:

Cell division that results in the production of two daughter cells genetically identical to the parent cell. It is responsible for growth, repair, and cell renewal. Mitosis involves several phases from the initial interphase:

- Prophase: Chromosomes condense and become visible. The nuclear envelope begins to break down.

- Metaphase: Chromosomes align at the equator of the cell.

- Anaphase: Sister chromatids (copies of chromosomes) separate and move towards opposite poles of the cell.

- Telophase: Two new daughter nuclei form, and the cell membrane pinches in, dividing the cytoplasm into two daughter cells.

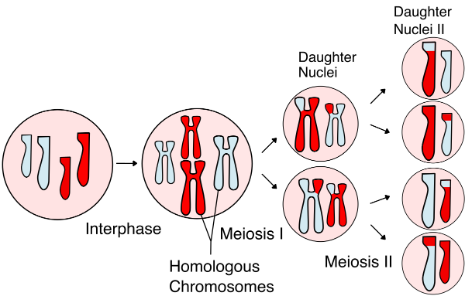

ii. Meiosis:

Cell division results in the production of four daughter cells, each with half the number of chromosomes (haploid) compared to the parent cell (diploid). Meiosis is essential for sexual reproduction, as it creates gametes (sperm and egg cells) with unique genetic combinations. Meiosis involves two meiotic divisions:

Meiosis I:

- Prophase I: Chromosomes condense and homologous chromosomes (chromosomes with the same genes) pair up. Crossing over, the exchange of genetic material between homologous chromosomes, can occur during this phase, leading to genetic diversity in the offspring.

- Metaphase I: Homologous chromosome pairs line up at the equator of the cell.

- Anaphase I: Homologous chromosomes separate and move towards opposite poles of the cell. This is the key difference between mitosis and meiosis I, as it results in the segregation of homologous chromosomes.

- Telophase I and Cytokinesis: Two daughter cells form, each containing half the number of chromosomes (haploid) as the parent cell. However, these daughter cells still have two copies of each gene (one from each parent) due to homologous chromosome pairing.

Meiosis II:

- Prophase II and Metaphase II: Similar to mitosis, chromosomes condense and align at the equator of the cell in each daughter cell from meiosis I.

- Anaphase II and Telophase II: Sister chromatids separate and move towards opposite poles, resulting in four haploid daughter cells (sperm or egg cells) with unique genetic combinations.

Tissue Types

Tissues are groups of similar cells that work together to perform a specific function. There are four main tissue types in the human body:

i. Epithelial Tissue:

Covers surfaces and lines body cavities, acting as a barrier and protecting underlying tissues. It also has functions like absorption, secretion, and sensory reception. Examples include:

- Stratified Squamous Epithelium: Found on the skin (provides protection)

- Simple Columnar Epithelium: Lines the intestines (absorption)

- Pseudostratified Columnar Epithelium:Lines the trachea (secretion and protection)

ii. Connective Tissue:

Provides support, structure, and connects organs. It also houses blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics. Examples include:

Bone Tissue:

Provides support and structure (skeleton)

Cartilage Tissue:

Provides support and cushions joints

Blood:

Transports oxygen, nutrients, and waste products

Adipose Tissue:

Stores energy and insulates the body

iii. Muscle Tissue: Enables movement. There are three types:

- Skeletal Muscle: Attached to bones, responsible for voluntary movement

- Smooth Muscle: Found in organs like the stomach and intestines, responsible for involuntary movement

- Cardiac Muscle:Found in the heart, responsible for pumping blood and is involuntary

iv. Nervous Tissue:

Carries messages throughout the body. It consists of neurons (nerve cells) and glial cells that support and protect neurons. Nervous tissue is responsible for sensation, movement, thought, and other body functions.

By understanding these cellular and tissue components, you’ll gain a foundational knowledge of how the human body is built and functions at a microscopic level. This knowledge is crucial for comprehending the physiological processes that maintain health and underlie various diseases.

Chapter 3: Integumentary System

The integumentary system, also known as the skin system, is the largest organ system in the human body. It acts as our first line of defense against the external environment, playing a vital role in various physiological functions. This chapter delves into the structure and functions of the skin, its appendages (hair and nails), and the different types of glands associated with it. We’ll also explore common skin disorders you might encounter in your nursing practice.

Structure and Functions of the Skin

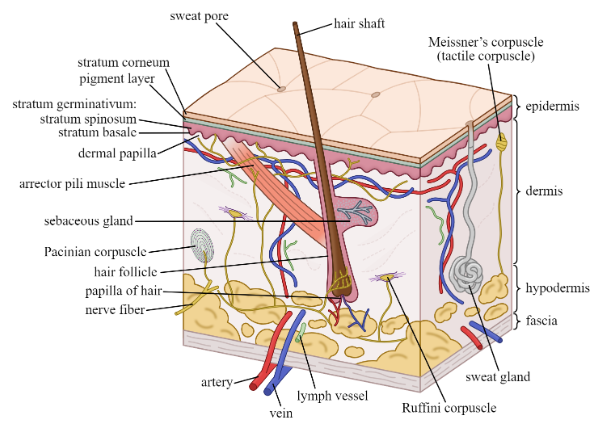

The skin is a complex organ composed of several layers, each with specialized functions:

i. Epidermis (Outermost Layer): Composed of stratified squamous epithelium, the epidermis is constantly renewing itself. It provides a barrier against pathogens, UV radiation, and water loss. Key layers include:

- Stratum Corneum: The outermost layer, made up of dead, keratinized cells that offer waterproofing and protection.

- Stratum Lucidum (Thin layer, present in palms and soles): Provides additional protection and aids in waterproofing.

- Stratum Granulosum: Produces keratin, a protein essential for skin structure and barrier function.

- Stratum Spinosum: Provides structural support and contains melanocytes, which produce melanin (pigment) for skin and hair color.

- Stratum Basale (Germinative Layer):The deepest layer, containing stem cells that constantly divide and replenish the overlying layers of the epidermis.

ii. Dermis (Middle Layer): The thick, strong, and connective tissue layer providing support and structure to the skin. It houses important structures like:

- Blood Vessels: Deliver oxygen and nutrients to the skin and help regulate body temperature.

- Nerve Endings: Enable sensations like touch, pain, pressure, and temperature.

- Hair Follicles: Anchor hair shafts.

- Sebaceous Glands: Secrete sebum, an oily substance that lubricates the skin and hair.

- Sweat Glands: Produce sweat to regulate body temperature.

iii. Hypodermis (Subcutaneous Layer): The deepest layer, composed of loose connective tissue and adipose tissue (fat). It provides insulation, stores energy, and cushions underlying structures.

Functions of the Skin

The skin plays a multitude of roles in maintaining health:

- Protection: The primary function of the skin is to act as a barrier against pathogens (bacteria, viruses), UV radiation, and harmful chemicals. The keratinized layer of the epidermis and the immune system within the dermis work together to shield the body.

- Temperature Regulation: The skin helps maintain body temperature through sweat production and blood flow regulation. Sweat evaporates from the skin’s surface, removing heat. Conversely, blood vessel constriction in the skin helps conserve heat.

- Sensory Perception: The skin is packed with nerve endings that allow us to perceive touch, pressure, pain, temperature, and vibration.

- Vitamin D Synthesis: The skin synthesizes vitamin D upon exposure to sunlight, essential for bone health and other bodily functions.

- Water Balance and Blood Pressure Regulation: The skin plays a minor role in regulating water balance by preventing excessive water loss through sweat production. Additionally, blood vessels in the dermis can constrict or dilate, influencing blood pressure.

- Excretion: Sweat glands eliminate waste products like urea and salts through sweat.

- Nonverbal Communication: Skin color changes due to blushing or pallor can convey emotions.

Hair, Nails, and Glands

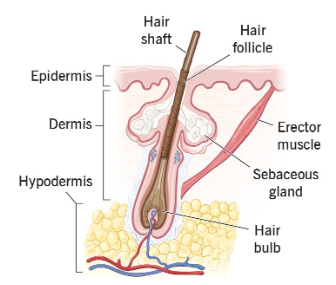

Hair and nails are accessory structures of the skin, derived from the epidermis.

- Hair: Grows from hair follicles in the dermis. Hair provides insulation, protects the scalp from UV radiation, and can aid in sensory perception.

- Nails: Composed of hard keratin, nails protect the tips of fingers and toes, assisting with grasping and scratching.

The skin houses various glands that secrete different substances:

i. Sebaceous Glands: Located near hair follicles, sebaceous glands secrete sebum, a lubricating oil that keeps the skin and hair supple and waterproof.

ii. Sweat Glands: Found throughout the skin, sweat glands produce sweat to regulate body temperature. There are two main types:

- Eccrine Glands: Distributed across most of the body, eccrine glands produce a watery sweat for thermoregulation.

- Apocrine Glands: Primarily located in the armpits and groin, apocrine glands produce a thicker, milky sweat that acquires an odor when broken down by bacteria.

iii. Apocrine Sweat Glands: These glands become active during puberty and contribute to body odor.

Common Skin Disorders

- Acne:

A common inflammatory skin condition caused by clogged pores, excess oil production, and bacterial growth. It typically affects the face, chest, back, and shoulders. Acne vulgaris is the most common type, presenting with blackheads, whiteheads, pimples, and nodules.

- Eczema:

A group of inflammatory skin conditions causing dry, itchy, and irritated skin. Different types of eczema exist, including atopic dermatitis (common in children), contact dermatitis (triggered by allergens or irritants), and seborrheic dermatitis (affecting oily areas like scalp and face).

- Psoriasis:

A chronic autoimmune disorder that causes rapid skin cell growth, leading to thick, red, scaly patches. It can affect any part of the body but commonly appears on the elbows, knees, scalp, and lower back.

- Fungal Infections:

Athlete’s foot, ringworm, and jock itch are common fungal infections that cause itching, burning, and scaling of the skin.

- Bacterial Infections: Impetigo, a contagious bacterial skin infection, causes red, blistering sores, typically on the face, arms, and legs. Cellulitis is another bacterial infection that causes redness, swelling, and pain, usually on the legs.

- Skin Cancer:

The most common cancer type, skin cancer arises from abnormal growth of skin cells. Melanoma, the most serious form, develops from pigment-producing cells (melanocytes). Early detection is crucial for successful treatment.

Understanding these structures, functions, and common disorders of the integumentary system is essential for nurses. By recognizing signs and symptoms of skin problems, nurses can provide appropriate care, educate patients on preventive measures, and collaborate with physicians for diagnosis and treatment.

Chapter 4: Skeletal System

Skeletal System: The Body’s Framework

The skeletal system provides the body with its framework, support, structure, and protection for vital organs. It also plays a role in movement, blood cell production, and mineral storage. This chapter delves into the intricate structure and function of bones, the major bones of the body, different types of joints and their movements, cartilage varieties, and common bone disorders you might encounter as a nurse.

Bone Structure and Function

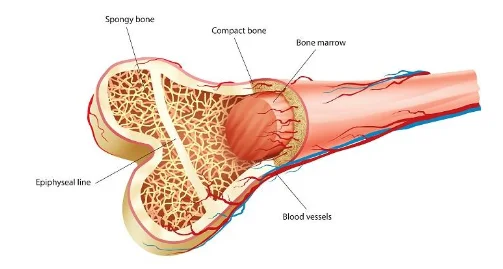

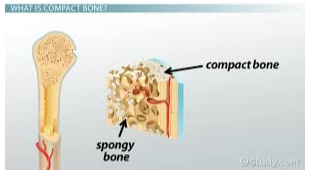

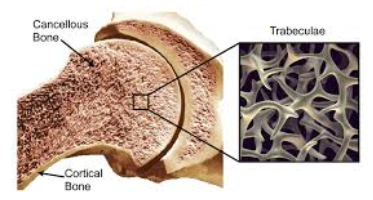

Bones are surprisingly dynamic organs, constantly undergoing remodeling throughout life. They are composed of a hard, dense outer layer (compact bone) and a lighter, spongy inner core (cancellous bone).

Compact Bone:

Made up of osteons (Haversian systems), which are cylindrical units containing concentric rings of lamellae (hard plates) composed of collagen fibers and hydroxyapatite crystals (calcium phosphate). This structure provides strength and rigidity to bones.

Cancellous Bone:

A lattice-like network of thin bony trabeculae, filled with red or yellow bone marrow. It is lighter yet stronger than it appears and contributes to bone strength and flexibility. It also houses red bone marrow, responsible for blood cell production.

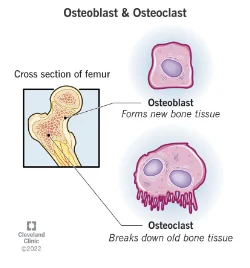

Bone Cells:

Several cell types contribute to bone structure and function:

- Osteoblasts: Bone-forming cells responsible for building new bone tissue.

- Osteocytes: Mature bone cells that maintain bone structure and regulate mineral homeostasis.

- Osteoclasts: Bone-resorbing cells that break down old or damaged bone tissue, enabling bone remodeling.

Functions of Bones:

The skeletal system fulfills various crucial functions:

- Support and Structure: Bones provide the body with its framework, supporting organs and soft tissues.

- Movement: Bones act as levers, working with muscles to facilitate movement at joints.

- Protection: Bones form a protective cage around vital organs like the brain, heart, and lungs.

- Blood Cell Production: Red bone marrow in cancellous bone produces red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- Mineral Storage: Bones act as a reservoir for calcium, phosphorus, and other minerals, essential for various bodily functions.

- Acid-Base Balance: Bones play a minor role in maintaining acid-base balance by releasing or storing calcium carbonate.

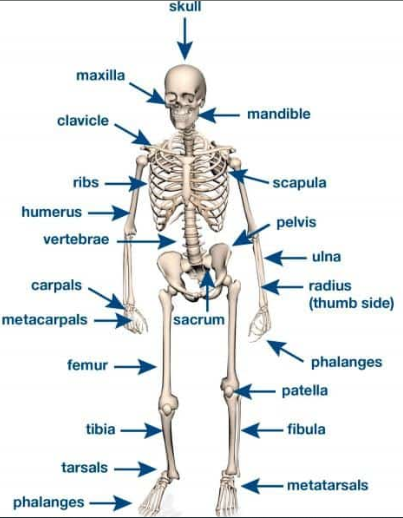

Major Bones of the Body

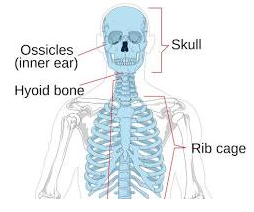

The human skeleton can be divided into two main parts:

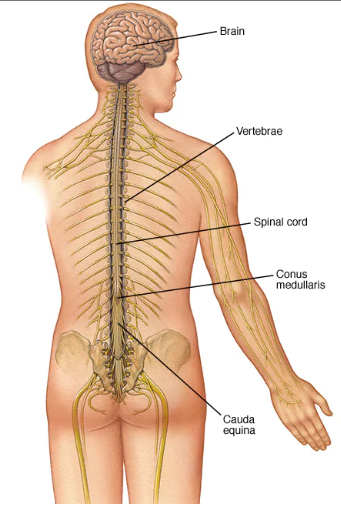

Axial Skeleton: The central axis of the body, consisting of 80 bones:

i. Skull:

Protects the brain and houses sensory organs (eyes, ears, nose, and taste buds).

ii. Vertebral Column (Spine): Provides support, flexibility, and protection for the spinal cord. It consists of 24 vertebrae (cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccyx).

iii. Rib Cage:

Composed of 12 pairs of ribs that attach to the spine and sternum (breastbone), protecting the heart, lungs, and major blood vessels.

iv. Sternum (Breastbone):

Flat bone located in the front of the chest wall, connecting the ribs.

v. Appendicular Skeleton: The bones of the limbs and the shoulder and pelvic girdles, consisting of 126 bones:

- Pectoral Girdle (Shoulder Girdle):

Connects the upper limbs (arms) to the axial skeleton. It comprises the clavicle (collarbone) and scapula (shoulder blade).

- Upper Limb: Composed of the humerus (upper arm bone), radius and ulna (forearm bones), carpals (wrist bones), metacarpals (hand bones), and phalanges (finger bones).

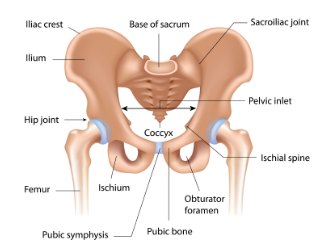

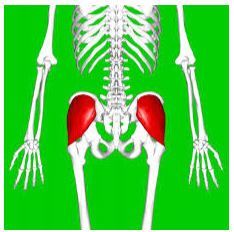

- Pelvic Girdle:

A bony ring that connects the lower limbs (legs) to the axial skeleton. It is formed by the ilium, ischium, and pubis (fused to form the innominate bone on each side).

- Lower Limb: Composed of the femur (thigh bone), tibia and fibula (lower leg bones), tarsals (ankle bones), metatarsals (foot bones), and phalanges (toe bones).

Joints

Joints are the points of articulation where two or more bones connect. They provide mobility and stability to the skeletal system. Different types of joints allow for varying degrees of movement.

Types of Joints:

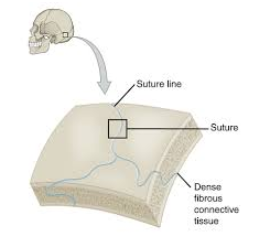

Fibrous Joints:

Immovable joints where bones are joined by dense fibrous connective tissue. Examples include the sutures of the skull.

Cartilaginous Joints: Slightly movable joints where bones are connected by cartilage. Examples include the symphysis pubis (joint between the pubic bones) and the intervertebral joints (between vertebrae).

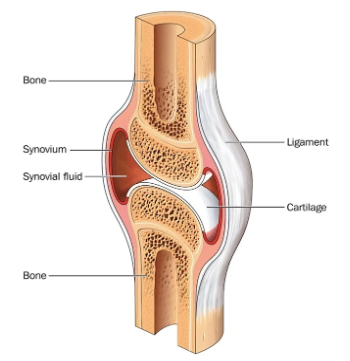

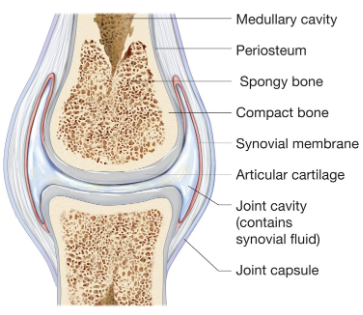

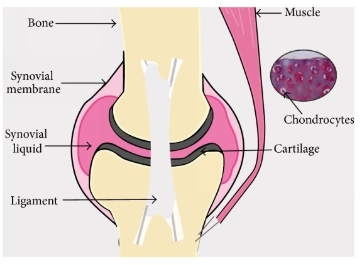

Synovial Joints:

Freely movable joints where bones are separated by a synovial cavity filled with synovial fluid. This fluid reduces friction and nourishes the joint cartilage. Synovial joints are further classified based on the movement they allow:

- Hinge Joints:Allow movement in one plane (bending and straightening). Examples include the knee and elbow joints.

- Ball-and-Socket Joints: Allow movement in multiple planes (flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, circumduction, and rotation). Examples include the shoulder and hip joints.

- Saddle Joints: Allow movement in two planes (flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction) with some rotation. The carpometacarpal joint at the base of the thumb is an example.

- Gliding Joints: Allow gliding movements in multiple planes. Examples include the joints between the carpals (wrist bones) and the tarsals (ankle bones).

- Pivot Joints: Allow rotation around a single axis. The atlantoaxial joint (between the first and second cervical vertebrae) is an example, enabling us to turn our head side-to-side.

Cartilage Types

Cartilage is a type of connective tissue that provides cushioning, support, and structure at joints. There are three main types:

- Hyaline Cartilage:

The most abundant type, found covering the ends of bones at synovial joints, the nose, and trachea. It is smooth, glassy, and avascular (lacks blood vessels).

- Fibrocartilage:A tough, flexible type found in intervertebral discs, the pubic symphysis, and the menisci (cartilage pads) in the knee joint. It contains a mix of collagen fibers and chondrocytes (cartilage cells).

- Elastic Cartilage:

Provides elasticity and support to structures like the external ear and the epiglottis (flap covering the trachea). It contains elastic fibers in addition to collagen fibers and chondrocytes.

Common Bone Disorders

Several factors can contribute to bone disorders. Here are some common ones you might encounter as a nurse:

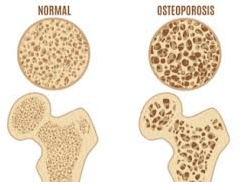

- Osteoporosis:

A condition characterized by decreased bone density, making bones weak and prone to fractures. It is more common in older adults, especially women.

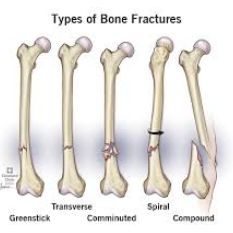

- Fractures:

A broken bone, which can occur due to trauma, falls, osteoporosis, or underlying diseases. Different types of fractures exist, such as closed (clean break), open (bone protrudes through the skin), comminuted (bone breaks into multiple pieces), and greenstick (fracture in a child’s bone that doesn’t break completely).

- Arthritis:

A general term for joint inflammation, causing pain, stiffness, and swelling. Osteoarthritis is the most common type, resulting from wear and tear of the joint cartilage. Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disorder that attacks the synovial membrane of joints.

- Bone Tumors:

Abnormal growths in bone that can be benign (noncancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Common bone cancers include osteosarcoma and chondrosarcoma.

Understanding the structure, function, major bones, joints, cartilage types, and common disorders of the skeletal system is fundamental for nurses. This knowledge equips you to assess patients for bone-related problems, provide appropriate care, educate patients on preventive measures, and collaborate with physicians for diagnosis and treatment.

Chapter 5: Muscular System

The Muscular System: Engine of Movement

The muscular system is the powerhouse behind our movements, maintaining posture, stabilizing joints, and enabling various bodily functions. This chapter delves into the three main muscle types, their structure and function, the fascinating mechanism of nerve-muscle communication, and major muscle groups with their specific actions.

Muscle Types

The human body houses three distinct types of muscle tissue, each specialized for a particular function:

- Skeletal Muscle (Striated Muscle):

Voluntary muscles attached to bones by tendons. They are responsible for conscious movements like walking, running, and lifting objects. Skeletal muscles are striated, meaning they have a striped appearance due to the arrangement of contractile proteins within the muscle cells.

- Smooth Muscle:

Involuntary muscles found in the walls of organs like the stomach, intestines, blood vessels, and airways. Smooth muscle contracts and relaxes to regulate organ function, such as digestion, blood flow, and breathing. Smooth muscle lacks striations and appears smooth under a microscope.

- Cardiac Muscle:

Involuntary muscle that forms the wall of the heart. It contracts rhythmically and continuously throughout life to pump blood throughout the body. Cardiac muscle has striations similar to skeletal muscle but possesses unique features to enable its tireless function.

Muscle Structure and Function

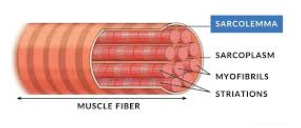

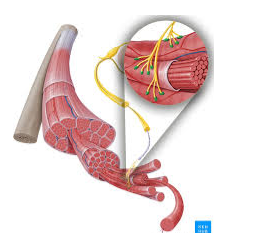

Muscle cells, also called myocytes, share some common features across the three types:

- Sarcolemma: The cell membrane of a muscle cell.

- Sarcoplasm: The cytoplasm of a muscle cell, containing organelles and myofibrils (contractile elements).

- Myofibrils: Bundles of myofilaments (protein filaments) responsible for muscle contraction. The two main types of myofilaments are actin and myosin.

Skeletal Muscle Structure:

Skeletal muscle cells are the longest in the body, often multinucleated (having multiple nuclei). They are organized into fascicles (bundles) surrounded by connective tissue layers. Within each muscle cell, myofibrils are arranged in a highly organized pattern, giving skeletal muscle its striated appearance.

Smooth Muscle Structure:

Smooth muscle cells are spindle-shaped and uninucleated (having one nucleus). They lack the organized sarcomeric structure of skeletal muscle and contain actin and myosin filaments arranged differently.

Cardiac Muscle Structure:

Cardiac muscle cells are branched and uninucleated, with striations similar to skeletal muscle. However, cardiac muscle cells interconnect at specialized junctions called intercalated discs, allowing for coordinated contraction of the heart chambers.

Muscle Contraction

The basic unit of muscle contraction is the sarcomere, a segment of a myofibril containing actin and myosin filaments. Here’s a simplified overview of the muscle contraction process:

- Neuromuscular Junction: A nerve impulse travels down a motor neuron and reaches the neuromuscular junction (the synapse between the nerve and muscle cell).

- Calcium Release: The nerve impulse triggers the release of calcium ions from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (a specialized network of membranes within the muscle cell).

- Calcium Binding: Calcium ions bind to troponin on the actin filaments, removing the blocking effect on myosin binding sites.

- Power Stroke: Myosin heads bind to actin, forming cross-bridges. Myosin undergoes a power stroke, pulling the actin filaments towards the center of the sarcomere, causing muscle shortening (contraction).

- Relaxation: When the nerve impulse ceases, calcium is pumped back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Troponin blocks the myosin binding sites on actin, and the muscle fiber relaxes.

Neuromuscular Junction

The neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is the critical link between the nervous system and the muscular system. It ensures coordinated muscle activation based on nerve signals. Here’s what happens at the NMJ:

- Action Potential: A nerve impulse (action potential) travels down the axon of a motor neuron.

- Neurotransmitter Release: The action potential triggers the release of acetylcholine (ACh), a neurotransmitter, from the synaptic vesicles at the motor neuron terminal.

- ACh Binding: ACh binds to specific receptors on the muscle cell membrane (motor end plate).

- End Plate Potential (EPP): ACh binding generates an end plate potential (EPP), a localized depolarization event in the muscle cell membrane.

- Muscle Action Potential: If the EPP reaches a threshold level, it triggers an action potential in the muscle cell membrane, which propagates throughout the cell.

- Muscle Contraction: The action potential leads to calcium release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, initiating muscle contraction as described earlier.

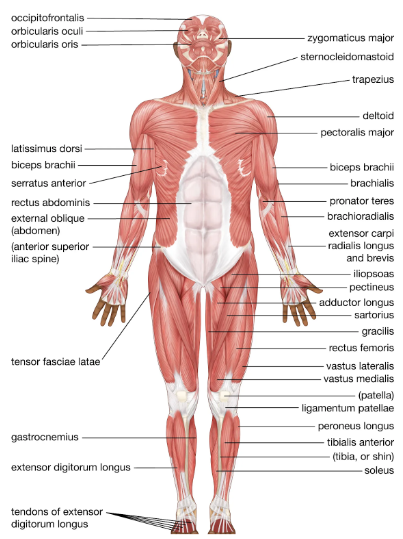

Major Muscle Groups and Functions

The over 600 skeletal muscles in the human body can be grouped based on their location and function. Here’s a breakdown of some major muscle groups and their key actions:

i. Head and Neck:

- Masseter: Located on the side of the face, responsible for chewing.

- Temporalis: Located on the temple, assists with jaw movement and closing the mouth.

- Sternocleidomastoid: Located on the side of the neck, helps with head rotation, bending, and tilting.

- Facial Muscles: Numerous muscles control facial expressions like smiling, frowning, squinting, and blinking.

ii. Trunk:

- Pectoralis Major: Located on the chest, responsible for shoulder flexion, adduction, and internal rotation (movement of the arm towards the midline).

- Pectoralis Minor: Located under the pectoralis major, assists with shoulder movement and posture.

- Latissimus Dorsi: Broad muscle on the back, responsible for arm extension, adduction, and rotation (movement of the arm away from the midline).

- Erector Spinae: Group of muscles along the spine, responsible for spinal extension, posture maintenance, and trunk rotation.

- Rectus Abdominis: Vertical muscles on the anterior abdominal wall, responsible for trunk flexion and core stability.

- Obliques: Muscles on the sides of the abdomen, aid in trunk rotation, bending, and core stability.

iii. Upper Limbs:

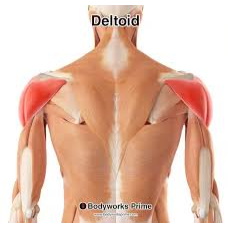

- Deltoid:

Fan-shaped muscle on the shoulder, responsible for shoulder abduction (lifting the arm away from the body).

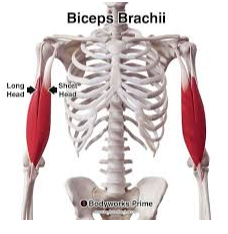

- Biceps Brachii:

Muscle on the front of the upper arm, responsible for elbow flexion (bending the arm).

- Triceps Brachii:

Muscle on the back of the upper arm, responsible for elbow extension (straightening the arm).

- Brachialis: Muscle located beneath the biceps brachii, assists with elbow flexion.

- Forearm Muscles: A group of muscles in the forearm control wrist and finger movements like flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and rotation.

iv. Lower Limbs:

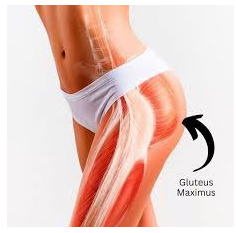

- Gluteus Maximus:

Large muscle on the buttocks, responsible for hip extension, abduction, and external rotation.

- Gluteus Medius:

Muscle on the side of the hip, responsible for hip abduction and stabilization.

- Quadriceps Femoris: Group of four muscles on the front of the thigh, responsible for knee extension (straightening the leg).

- Hamstrings: Group of three muscles on the back of the thigh, responsible for knee flexion (bending the leg) and hip extension.

- Calf Muscles:

Gastrocnemius and soleus muscles on the back of the lower leg, responsible for plantar flexion (pointing the toes down) and ankle movement.

- Tibialis Anterior:

Muscle on the front of the lower leg, responsible for dorsiflexion (pointing the toes up) and ankle movement.

Additional Notes:

- This list is not exhaustive, and many other smaller muscles contribute to specific movements and functions.

- Synergistic muscles work together to produce a coordinated movement.

- Antagonistic muscles work in opposition to each other, allowing for controlled movement (e.g., biceps brachii for flexion and triceps brachii for extension of the elbow joint).

By understanding the different muscle types, their structure and function, the neuromuscular junction, and major muscle groups, you gain a solid foundation for comprehending human movement and the potential causes of muscle weakness or dysfunction. This knowledge is crucial for nurses in various settings, from assisting patients with mobility to recognizing signs and symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders.

Chapter 6: Nervous System

The Nervous System: A Deep Dive into the Body’s Control Center

The human nervous system is the most intricate and awe-inspiring organ system in the body. It acts as the body’s maestro, coordinating all activities, processing information from the environment, and generating responses to maintain a stable internal state (homeostasis). This chapter delves into the depths of the nervous system, exploring its organization, cellular components, communication mechanisms, and the symphony of functions it conducts.

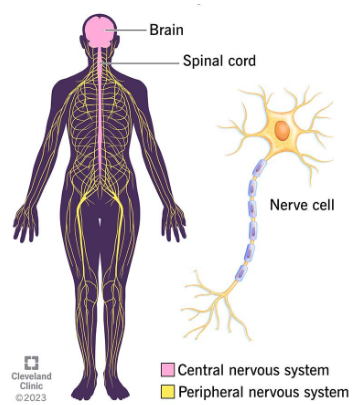

Central Nervous System (CNS): The Command Center

The CNS serves as the processing headquarters of the nervous system, housed within the protective bony cage of the skull and vertebral column. It comprises two major structures:

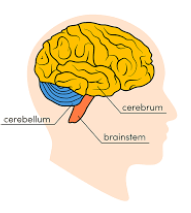

Brain:

The most complex organ, responsible for higher-order functions like consciousness, thought, memory, learning, emotions, and control of many bodily activities. Key regions of the brain include:

- Cerebrum:Divided into two hemispheres, it is the largest part of the brain and governs consciousness, sensation, movement, thinking, memory, and learning.

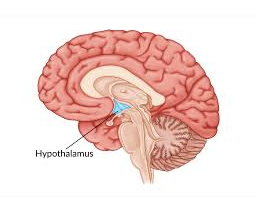

- Diencephalon:Located deep within the brain, it houses structures like the thalamus (relay center for sensory information) and hypothalamus (plays a vital role in regulating body temperature, hunger, thirst, sleep-wake cycle, and hormone release).

- Brainstem:Connects the brain to the spinal cord and controls essential functions like breathing, heart rate, digestion, and reflexes.

- Cerebellum:Coordinates movement, balance, and posture.

Spinal Cord:

A long, cylindrical bundle of nervous tissue encased within the vertebral column. It serves two crucial functions:

- Carries Sensory Information: Sensory neurons transmit information about touch, pain, temperature, and other sensations from the periphery to the brain via the spinal cord.

- Conducts Motor Commands:The brain sends motor commands down the spinal cord to muscles, enabling movement and reflexes.

Peripheral Nervous System (PNS): The Body’s Network

The PNS acts as the body’s extensive network, connecting the CNS to all parts. It can be further categorized into two functional divisions:

- Somatic Nervous System (SNS): The voluntary nervous system, responsible for controlling skeletal muscles. It allows us to consciously initiate movements like walking, talking, and writing.

- Autonomic Nervous System (ANS): The involuntary nervous system, responsible for regulating functions we don’t consciously control, such as heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, breathing, and pupil dilation. The ANS is further subdivided into two antagonistic branches:

-

- Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS): Often referred to as the “fight-or-flight” system, it mobilizes the body during stress or exertion. It increases heart rate, breathing rate, blood pressure, and blood sugar levels, preparing the body for action.

- Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS): The “rest-and-digest” system, promotes body functions during relaxation and digestion. It decreases heart rate, breathing rate, blood pressure, and blood sugar levels, conserving energy.

Structure and Function of Neurons: The Information Messengers

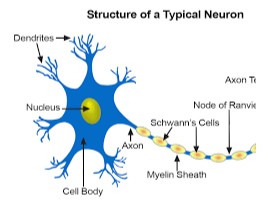

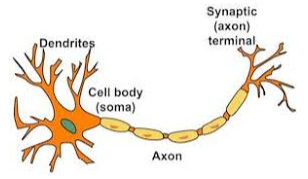

The fundamental unit of the nervous system is the neuron, a specialized cell responsible for transmitting electrical signals and chemical messages throughout the body. Here’s a closer look at a neuron’s structure and function:

- Cell Body (Soma):

The metabolic center of the neuron, containing the nucleus and other organelles essential for cell function.

- Dendrites: Short, branching extensions that receive signals from other neurons. They act as the receiving antennae of a neuron.

- Axon: A single, long fiber that transmits electrical signals away from the cell body to other neurons, muscles, or glands. It acts as the communication line of a neuron. Some axons are wrapped in a fatty insulating layer called the myelin sheath, which speeds up signal transmission.

- Synapse:The junction where communication between neurons occurs. It consists of a presynaptic terminal (axon terminal of the sending neuron), a postsynaptic membrane (dendrite or cell body of the receiving neuron), and a synaptic cleft (the space between them).

Neurons, Synapses, and Neurotransmitters: The Language of the Nervous System

Neurons don’t directly connect with each other. They communicate through specialized junctions called synapses. Here’s how information travels through the nervous system:

The Nervous System

Neurons, Synapses, and Neurotransmitters

- Action Potential: This can occur due to sensory information received or another neuron firing an excitatory signal at a synapse.

- Propagation: The action potential travels down the axon, aided by the myelin sheath if present. The myelin sheath acts like insulation on a wire, allowing the signal to travel faster and more efficiently.

- Neurotransmitter Release: When the action potential reaches the axon terminal, it triggers the release of neurotransmitters, chemical messengers, into the synaptic cleft.

- Neurotransmitter Binding: Neurotransmitters diffuse across the synaptic cleft and bind to specific receptors on the postsynaptic membrane.

- Excitatory or Inhibitory Effect: Depending on the neurotransmitter and receptor type, the receiving cell may experience an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) or an inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP).

-

- Excitatory Postsynaptic Potential (EPSP): If the neurotransmitter binding leads to an EPSP, the receiving cell becomes more likely to generate an action potential. This is because EPSPs make the postsynaptic membrane more positive, bringing it closer to the threshold for firing an action potential.

- Inhibitory Postsynaptic Potential (IPSP): Conversely, if the neurotransmitter binding leads to an IPSP, the receiving cell becomes less likely to generate an action potential. This is because IPSPs make the postsynaptic membrane more negative, moving it further away from the threshold for firing an action potential.

Major Functions of the Nervous System:

The nervous system conducts a vast symphony of functions within the body, ensuring its proper operation and adaptability. Here’s a detailed breakdown of its key roles:

- Sensation: This involves detecting changes in the internal and external environment through specialized sensory receptors located throughout the body. These receptors respond to various stimuli like touch, pain, temperature, taste, smell, light, and sound. Sensory information is then transmitted via sensory neurons to the CNS for processing.

- Integration: The CNS receives sensory information from various parts of the body, interprets it, and determines an appropriate response. This involves complex processing within different brain regions.

- Movement: The CNS coordinates and controls voluntary and involuntary movements. Voluntary movements are initiated consciously, while involuntary movements occur without conscious control (e.g., reflexes). The motor cortex in the cerebrum plays a crucial role in planning and initiating voluntary movements. Motor commands are then transmitted via motor neurons to the muscles for execution.

- Homeostasis: The nervous system plays a vital role in maintaining a stable internal environment. It regulates various physiological processes like body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, breathing, digestion, and fluid balance. This is achieved through a complex interplay between the CNS, ANS, and various organs.

- Thinking and Learning: Higher-order cognitive functions like thought, memory, learning, and problem-solving are mediated by specific brain regions, particularly the cerebrum. These functions involve complex processing, integration of information, and the ability to adapt based on experience.

- Language: The ability to comprehend and produce spoken and written language is a remarkable feat facilitated by specific brain regions like Broca’s area (responsible for speech production) and Wernicke’s area (responsible for language comprehension).

- Emotions: The nervous system is intricately involved in generating and regulating emotions like fear, anger, sadness, and joy. The limbic system, a group of structures deep within the brain, plays a key role in processing emotions.

- Sleep-Wake Cycle: The nervous system regulates the sleep-wake cycle, ensuring periods of rest and activity. The hypothalamus plays a crucial role in this process, influenced by various factors like light exposure and internal body rhythms.

Additional Notes:

- The nervous system is an incredibly complex and dynamic system. This chapter provides a foundation, but further exploration reveals intricate details about specific brain functions, neural pathways, and the diverse range of neurotransmitters.

- Understanding the nervous system’s structure and function is crucial for nurses in various settings. It equips them to assess neurological problems, provide appropriate care for patients with nervous system disorders, and collaborate with physicians for diagnosis and treatment.

- This chapter has incorporated additional details on the types of neurotransmitters (excitatory and inhibitory) and their effects on the postsynaptic membrane (EPSPs and IPSPs) to provide a more comprehensive understanding of neuronal communication.

This in-depth exploration of the nervous system highlights its remarkable complexity and its role as the maestro of the human body. By delving into the structure and function of neurons, the language of neurotransmitters, and the vast array of functions it governs, we gain a deeper appreciation for this intricate system that orchestrates our every thought, movement, and sensation.

Chapter 7: Endocrine System

The endocrine system, often referred to as the body’s chemical communication network, plays a vital role in regulating numerous physiological processes. It functions through a network of glands that produce hormones, chemical messengers that travel through the bloodstream to target organs and tissues throughout the body. These hormones exert a wide range of effects, influencing growth, development, metabolism, reproduction, mood, and many other functions.

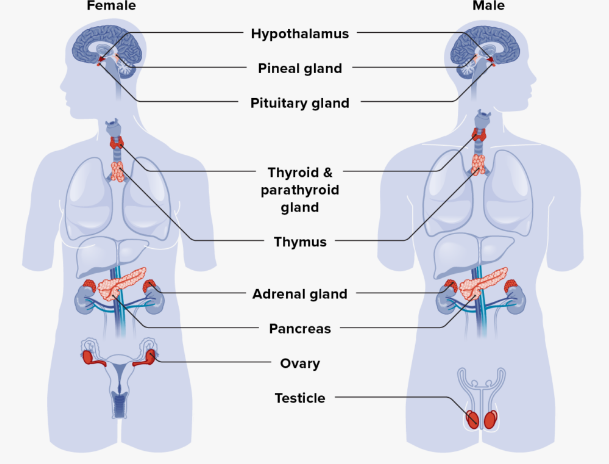

Major Endocrine Glands and Their Hormones

The endocrine system comprises several glands located strategically within the body. Here’s a breakdown of some key endocrine glands and their principal hormones:

A. Hypothalamus:

Located deep within the brain, the hypothalamus acts as the master control center of the endocrine system. It doesn’t produce hormones directly but instead secretes releasing hormones that stimulate the release of hormones from other endocrine glands.

- Releasing Hormones:Examples include thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH).

B. Pituitary Gland: Often referred to as the “master gland” due to its response to hypothalamic signals, the pituitary gland secretes various hormones that influence other endocrine glands and directly regulate various functions.

i) Anterior Pituitary Hormones:

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH): Stimulates the thyroid gland to produce thyroid hormones.

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH): Stimulates the adrenal cortex to release cortisol.

- Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and Luteinizing hormone (LH): Regulate development and function of the gonads (ovaries in females, testes in males).

- Prolactin: Stimulates milk production in females.

- Growth hormone (GH): Promotes growth and development.

ii) Posterior Pituitary Hormones:

- Oxytocin: Stimulates uterine contractions during childbirth and milk letdown during breastfeeding; also promotes bonding behaviors.

- Antidiuretic hormone (ADH):Regulates water balance by promoting water reabsorption in the kidneys.

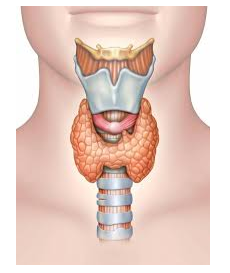

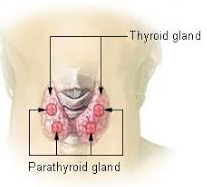

C. Thyroid Gland:

Located in the neck, the thyroid gland secretes thyroid hormones, crucial for regulating metabolism, growth, and development.

- Thyroxine (T4) and Triiodothyronine (T3):Increase metabolic rate, heart rate, and body temperature.

D. Parathyroid Glands:

Four tiny glands located behind the thyroid gland, the parathyroid glands produce parathyroid hormone (PTH), which regulates blood calcium levels.

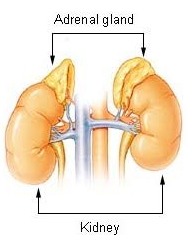

E. Adrenal Glands:

Located atop the kidneys, the adrenal glands are composed of two distinct regions: the adrenal cortex and the adrenal medulla.

i) Adrenal Cortex: The outer layer secretes steroid hormones, including:

- Cortisol: A stress hormone involved in regulating blood sugar levels, metabolism, and immune function.

- Aldosterone: Regulates blood pressure and electrolyte balance.

- Sex hormones (androgens and estrogens): Play a role in male and female sexual development and function, though these are produced in smaller quantities compared to the gonads.

ii) Adrenal Medulla:The inner layer secretes epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline) in response to stress or danger, collectively known as the “fight-or-flight” hormones.

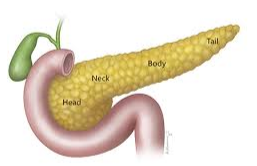

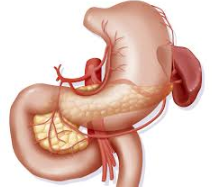

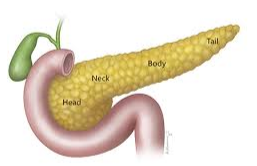

F. Pancreas:

Located behind the stomach, the pancreas functions as both an exocrine gland (producing digestive enzymes) and an endocrine gland. The endocrine portion of the pancreas secretes insulin and glucagon, hormones crucial for blood sugar regulation.

- Insulin: Lowers blood sugar levels by promoting glucose uptake into cells.

- Glucagon:Raises blood sugar levels by stimulating the breakdown of glycogen in the liver.

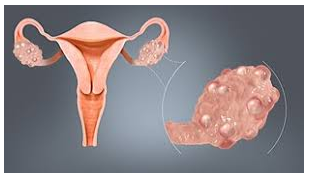

G. Ovaries:

The female reproductive organs located in the pelvic cavity, the ovaries produce several hormones, including:

- Estrogen: Stimulates female sexual development and function, regulates the menstrual cycle.

- Progesterone:Prepares the uterus for pregnancy and maintains the uterine lining during pregnancy.

H. Testes:

The male reproductive organs located in the scrotum, the testes produce testosterone, the primary male sex hormone responsible for male sexual development and function, muscle mass, and bone density.

Functions of Hormones

Hormones exert a wide range of effects on various target organs and tissues throughout the body. Here are some key functions of hormones:

- Regulating Metabolism: Hormones like thyroid hormones, insulin, and glucagon play a critical role in regulating metabolism, the body’s process of converting food into energy. They influence how efficiently the body uses energy, stores nutrients, and maintains blood sugar levels.

- Growth and Development: Hormones like growth hormone, thyroid hormones, sex hormones (estrogen, testosterone), and insulin are essential for proper growth and development from childhood to adulthood. They influence bone growth, muscle development, and the maturation of sexual organs.

- Reproduction: Sex hormones (estrogen, progesterone, testosterone) are central to regulating the reproductive system in both males and females. They control the development of sexual organs, menstrual cycle, ovulation, sperm production, and other aspects of reproduction.

- Mood and Behavior: Hormones like serotonin, dopamine, and cortisol can significantly impact mood, behavior, and emotional well-being. Imbalances in these hormones can contribute to anxiety, depression, and stress.

- Maintaining Homeostasis: The endocrine system plays a vital role in maintaining homeostasis, a stable internal environment. Hormones like cortisol, aldosterone, ADH, and insulin help regulate blood pressure, blood sugar levels, water balance, and electrolyte balance.

- Response to Stress: The adrenal glands secrete epinephrine and norepinephrine (fight-or-flight hormones) in response to stress or danger. These hormones increase heart rate, breathing rate, blood sugar levels, and alertness, preparing the body to react.

Regulation of Hormone Release

The release of hormones from endocrine glands is tightly regulated through a feedback loop system. Here’s how it works:

i) Negative Feedback: This is the most common type of feedback loop in the endocrine system. It ensures hormone levels don’t become too high.

- Example: When blood sugar levels rise after a meal, the pancreas releases insulin to lower them. As blood sugar levels decrease and return to normal, the release of insulin is inhibited.

ii) Positive Feedback: This type of feedback loop is less common but can be crucial in certain situations. It amplifies the release of a hormone.

- Example: During childbirth, oxytocin is released from the posterior pituitary gland, stimulating uterine contractions. As contractions become stronger, more oxytocin is released, creating a positive feedback loop that helps expel the baby.

Common Endocrine Disorders

Several disorders can arise due to malfunctioning of the endocrine glands or problems with hormone regulation. Here are some common examples:

- Diabetes mellitus: A group of disorders characterized by high blood sugar levels due to either insufficient insulin production (type 1 diabetes) or insulin resistance (type 2 diabetes).

- Thyroid disorders: These can include hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) and hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid), which can cause a variety of symptoms affecting metabolism, energy levels, mood, and weight.

- Cushing’s syndrome: Occurs when the body is exposed to chronically high levels of cortisol, leading to symptoms like weight gain, fatty deposits around the upper back and neck, muscle weakness, and easy bruising.

- Addison’s disease: Results from the underproduction of cortisol and aldosterone from the adrenal cortex, causing fatigue, weakness, low blood pressure, and electrolyte imbalances.

- Growth hormone deficiency: Can lead to stunted growth and development in children.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A hormonal imbalance in women that can cause irregular periods, excessive hair growth, and difficulty getting pregnant.

Additional Notes:

- The endocrine system is a complex network with intricate interactions between different glands and hormones. Understanding this system is crucial for nurses in various settings.

- Nurses play a vital role in assessing patients for potential endocrine disorders, educating patients about their conditions, administering hormone replacement therapy, and monitoring treatment outcomes.

- This chapter has incorporated additional details on the feedback loop system that regulates hormone release to provide a more comprehensive understanding of hormonal control.

By exploring the major endocrine glands, their hormones, and the functions they regulate, we gain appreciation for the intricate chemical communication network that governs our bodies. Understanding hormonal imbalances and the disorders they can cause equips nurses with the knowledge to provide optimal care for patients with endocrine problems.

Chapter 8: Cardiovascular System

The cardiovascular system, often referred to as the circulatory system, is the body’s intricate plumbing network responsible for transporting life-sustaining blood throughout the body. This remarkable system functions like a well-oiled machine, ensuring the delivery of oxygen, nutrients, hormones, and waste products to all cells and tissues. Let’s embark on a deep dive into the anatomy, physiology, and potential disorders of this vital system.

Anatomy of the Heart: The Mighty Engine

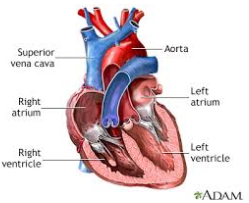

The heart, a muscular organ located in the center of the chest cavity, is the driving force behind the circulatory system. It’s divided into four chambers and equipped with valves that ensure proper blood flow direction. Here’s a detailed breakdown:

A. Chambers:

The heart has four chambers arranged in two upper chambers (atria) and two lower chambers (ventricles).

i) Atria (singular: atrium): These thin-walled chambers serve as receiving chambers for blood.

- Right atrium: Receives oxygen-depleted blood returning from the body via the superior vena cava (drains blood from the upper body) and inferior vena cava (drains blood from the lower body).

- Left atrium:Receives oxygen-rich blood returning from the lungs via the pulmonary veins.

ii) Ventricles (singular: ventricle): These thick-walled, muscular chambers are responsible for pumping blood throughout the body.

- Right ventricle: Pumps oxygen-depleted blood to the lungs for oxygenation via the pulmonary artery.

- Left ventricle: The thickest and most muscular chamber, pumps oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body via the aorta, the largest artery.

B. Valves: The heart valves act like one-way doors, ensuring blood flows in the correct direction within the heart.

i) Atrioventricular valves (AV valves): Located between the atria and ventricles.

- Tricuspid valve: Separates the right atrium and right ventricle. It has three cusps (flaps) and prevents backflow of blood into the right atrium when the ventricle contracts.

- Mitral valve (bicuspid valve): Separates the left atrium and left ventricle. It has two cusps and prevents backflow of blood into the left atrium when the ventricle contracts.

ii) Semilunar valves: Located at the exits of the ventricles.

- Pulmonary valve: Guards the opening of the pulmonary artery, preventing backflow of blood into the right ventricle.

- Aortic valve:Guards the opening of the aorta, preventing backflow of blood into the left ventricle.

C. Blood Flow: Blood follows a specific pathway through the heart:

- Oxygen-depleted blood from the body enters the right atrium via the superior and inferior vena cava.

- The tricuspid valve opens, and blood flows into the right ventricle.

- The right ventricle contracts, pushing blood through the pulmonary valve into the pulmonary artery.

- The pulmonary artery carries blood to the lungs for oxygenation.

- Oxygen-rich blood from the lungs returns to the left atrium via the pulmonary veins.

- The mitral valve opens, and blood flows into the left ventricle.

- The left ventricle contracts, pumping oxygen-rich blood through the aortic valve into the aorta, the main artery supplying the body.

Blood Vessels: The Body’s Network of Pipelines

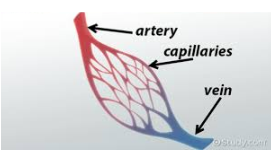

Blood vessels form an extensive network of tubes that transport blood throughout the body. They can be categorized into three main types:

a) Arteries:

Carry oxygen-rich blood away from the heart to all body tissues. They have thick, muscular walls with an elastic inner lining that can withstand the high pressure of blood pumped from the heart. Arteries branch out into smaller arteries, arterioles, and then narrow further into capillaries.

i. Artery Wall Structure: The arterial wall is composed of three layers:

- Tunica intima: The innermost layer, consisting of a smooth lining that facilitates blood flow.

- Tunica media: The middle layer, composed of smooth muscle cells and elastic fibers, responsible for maintaining blood pressure and regulating blood flow.

- Tunica externa: The outermost layer, composed of connective tissue, providing structural support and protection to the artery.

ii. Veins:

Carry oxygen-depleted blood back to the heart from the body tissues.

Blood Vessels

- Veins:

Carry oxygen-depleted blood back to the heart from the body tissues. They have thinner walls than arteries and contain valves that prevent backflow of blood. Veins generally travel alongside arteries and converge into larger veins that eventually drain into the superior and inferior vena cava, which return blood to the right atrium of the heart.

Vein Wall Structure: The vein wall is similar to arteries but has thinner layers:

- Tunica intima: The innermost layer, consisting of a thin endothelium.

- Tunica media: The middle layer, composed of a single layer of smooth muscle cells and less elastic tissue compared to arteries.

- Tunica externa: The outermost layer, composed of connective tissue, providing structural support.

Capillaries:

Microscopic, thin-walled vessels that connect arteries and veins. They are the sites where exchange of oxygen, nutrients, waste products, and fluids occurs between the blood and tissues. The vast network of capillaries allows for efficient delivery of essential substances to cells and removal of waste products.

Blood Composition and Functions

Blood, the life-sustaining fluid circulating within the cardiovascular system, is a complex mixture of several components:

Plasma: A liquid component that makes up about 55% of blood volume. It’s composed of 90% water and 10% solutes like:

- Proteins:

-

- Albumin: Transports various substances throughout the body, including hormones, fatty acids, and medications.

- Globulins: Play a role in the immune system by acting as antibodies to fight infection.

-

- Electrolytes: Minerals that help maintain proper fluid balance and nerve and muscle function (e.g., sodium, potassium, calcium, chloride).

- Nutrients: Transported to cells for energy production and building processes (e.g., glucose, amino acids, fatty acids).

- Hormones: Chemical messengers produced by glands that regulate various body functions.

- Waste Products: Carried away from cells for elimination (e.g., urea, carbon dioxide).

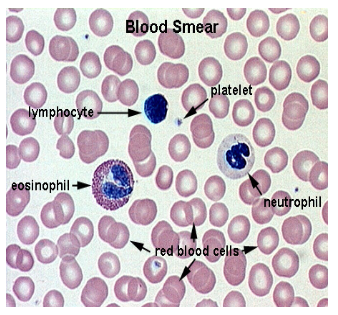

Red Blood Cells (RBCs):

Also known as erythrocytes, these are the most abundant cells in blood. They contain hemoglobin, a protein that binds oxygen and transports it from the lungs to tissues throughout the body. RBCs give blood its red color.

- White Blood Cells (WBCs):These are part of the body’s immune system and defend against infection and inflammation. There are several types of WBCs with specific functions.

- Platelets:Tiny cell fragments involved in blood clotting, which helps seal wounds and prevent excessive bleeding.

Blood Functions:

Blood plays a vital role in maintaining life by performing several essential functions:

- Transport: Blood delivers oxygen, nutrients (glucose, amino acids, fatty acids), hormones, and other essential substances to all body tissues.

- Waste Removal: Blood carries away carbon dioxide, a waste product of cellular respiration, and other waste products from tissues to the lungs, kidneys, and other organs for elimination.

- Regulation: Blood helps regulate body temperature by distributing heat throughout the body. It also transports hormones that influence various physiological processes.

- Protection: Blood is involved in clotting to prevent excessive bleeding after injury. White blood cells defend the body against infection and inflammation.

- Maintenance of Acid-Base Balance: Blood helps maintain a stable internal pH (acid-base balance), which is crucial for optimal functioning of cells and enzymes.

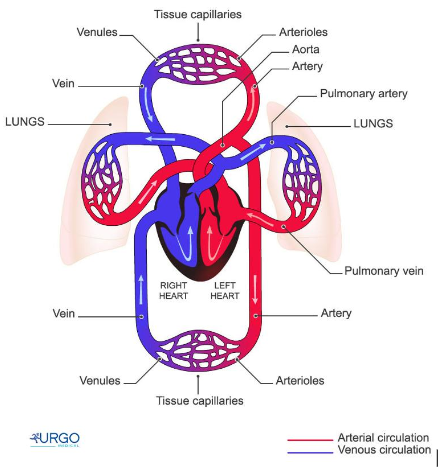

Physiology of Circulation: The Blood’s Journey

The cardiovascular system functions through a coordinated process called circulation, ensuring continuous blood flow throughout the body. Here’s a breakdown of the two main circulatory circuits:

Pulmonary Circulation (Lesser Circulation): This low-pressure circuit carries oxygen-depleted blood from the right side of the heart to the lungs for oxygenation, and then returns oxygen-rich blood to the left side of the heart.

- Oxygen-depleted blood from the body enters the right atrium via the superior and inferior vena cava.

- The tricuspid valve opens, allowing blood to flow into the right ventricle.

- The right ventricle contracts, pumping blood through the pulmonary valve into the pulmonary artery.

- The pulmonary artery carries blood to the lungs, where carbon dioxide is released and oxygen is absorbed into the bloodstream.

- Oxygen-rich blood from the lungs returns to the left atrium via the pulmonary veins.

Systemic Circulation (Greater Circulation): This high-pressure circuit carries oxygen-rich blood from the left side of the heart to all body tissues, and then returns oxygen-depleted blood back to the right side of the heart.

- Oxygen-rich blood from the lungs enters the left atrium via the pulmonary veins.

- The mitral valve opens, allowing blood to flow into the left ventricle.

- The left ventricle, the most powerful chamber, contracts, pumping oxygen-rich blood through the aortic valve into the aorta, the main artery supplying the body.

- The aorta branches out into smaller arteries, arterioles, and then capillaries, delivering oxygen and nutrients to all tissues.

- Oxygen-depleted blood and waste products enter the venules, which converge into veins, eventually draining into the superior and inferior vena cava, which return blood to the right atrium.

Regulation of Blood Flow:

Blood flow to different organs is not constant and can be regulated based on body needs. Here are some mechanisms involved:

- Nervous System Control: The autonomic nervous system (sympathetic and parasympathetic) can influence heart rate, blood vessel diameter (vasoconstriction or vasodilation), and blood pressure.

- Hormonal Control: Hormones like epinephrine (adrenaline) released during stress can increase heart rate and blood pressure.

- Local Blood Flow Regulation: Tissues can respond to changes in oxygen and carbon dioxide levels by adjusting blood flow to meet their needs.

Common Cardiovascular Disorders

Several diseases and conditions can affect the cardiovascular system, leading to significant health problems. Here are some common cardiovascular disorders:

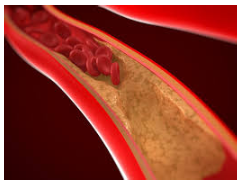

- Coronary artery disease (CAD):A narrowing of the coronary arteries due to plaque buildup, which can lead to angina (chest pain), heart attack, and heart failure.

- Heart attack (Myocardial infarction): Occurs when a blood clot blocks a coronary artery, depriving a part of the heart muscle of oxygen and blood supply, leading to tissue death.

- Heart failure: A condition where the heart weakens and is unable to pump blood effectively, leading to symptoms like fatigue, shortness of breath, and fluid buildup in the body (edema).

- Stroke: Occurs when a blood clot blocks or a blood vessel bursts in the brain, depriving brain tissue of oxygen and blood supply, leading to sudden loss of brain function.

- Arrhythmias: Abnormal heart rhythms, which can be too slow (bradycardia) or too fast (tachycardia), and can disrupt effective blood flow.

- Congenital heart defects: Birth defects of the heart structure, such as septal defects (holes in the walls between heart chambers) or valve abnormalities, which can impede blood flow.

- Atherosclerosis: A general term for the buildup of plaque (fatty deposits) in the walls of arteries, which can lead to various cardiovascular problems.

- High blood pressure (hypertension): Chronically elevated blood pressure can strain the heart and damage blood vessels, increasing the risk of stroke, heart attack, and kidney disease.

- Peripheral arterial disease (PAD): A narrowing of the arteries in the legs due to plaque buildup, which can reduce blood flow to the legs and cause pain, cramping, and even tissue death in severe cases.

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT): A blood clot that forms in a deep vein, usually in the legs, which can be life-threatening if the clot breaks loose and travels to the lungs (pulmonary embolism).

Additional Notes:

- The cardiovascular system is a complex and vital system for maintaining life. Understanding its anatomy, physiology, and potential disorders equips nurses to provide optimal care for patients with cardiovascular problems.

- Nurses play a crucial role in promoting cardiovascular health through education, risk factor management (e.g., diet, exercise, smoking cessation), monitoring vital signs, administering medications, and providing support to patients with cardiovascular conditions.

- This chapter has incorporated additional details on the regulation of blood flow and common cardiovascular disorders to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the cardiovascular system and its health.

By delving into the intricate workings of the cardiovascular system, we gain appreciation for the remarkable network that sustains life. Understanding the factors that contribute to cardiovascular disorders empowers nurses to play a vital role in promoting cardiovascular health and preventing these debilitating conditions.

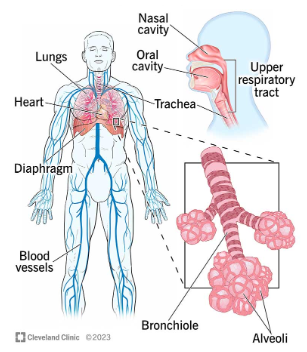

Chapter 9: Respiratory System

The respiratory system, also known as the pulmonary system, is a vital network of organs and structures responsible for gas exchange. It ensures a constant supply of oxygen (O₂) to the body’s cells and the removal of carbon dioxide (CO₂), a waste product of cellular respiration. This intricate system allows us to breathe in life and breathe out waste, maintaining a healthy internal environment for optimal functioning.

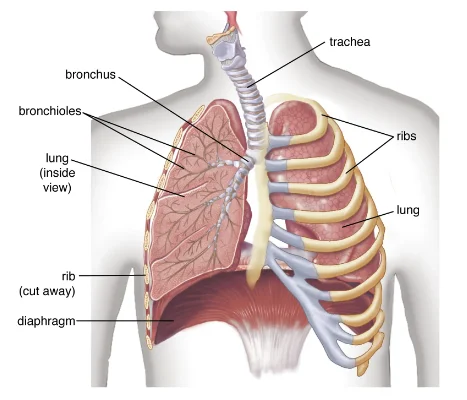

Anatomy of the Respiratory System: A Breathtaking Journey

The respiratory system can be divided into two main anatomical regions:

Upper Respiratory Tract: This comprises the structures involved in the initial stages of respiration, acting as a passageway for air.

- Nose:The external opening of the respiratory system, lined with mucous membrane that traps dust, allergens, and pathogens. The nose also contains olfactory receptors for the sense of smell.

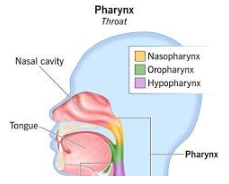

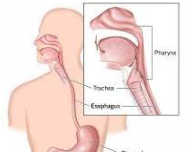

- Pharynx (Throat):

A muscular passageway shared by the respiratory and digestive systems. Air from the nose passes through the nasopharynx (upper part) before entering the oropharynx (middle part) and the laryngopharynx (lower part). The pharynx also houses the tonsils, lymphoid tissues that play a role in the immune system.

- Larynx (Voice Box):

A cartilaginous structure containing the vocal cords, which vibrate to produce sound during speech. The larynx also houses the epiglottis, a flap that closes over the larynx during swallowing to prevent food from entering the airway.

- Trachea (Windpipe):A muscular tube lined with ciliated epithelium that traps dust and debris. The trachea branches into the left and right main bronchi at the carina (inferior end).

Lower Respiratory Tract: This comprises the structures involved in gas exchange between the air and the bloodstream.

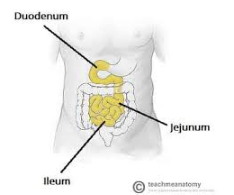

- Bronchi (singular: bronchus): The main bronchi divide further into secondary bronchi, then tertiary bronchi, and finally into bronchioles, which are smaller tubes without cartilage rings.

- Bronchioles: These further branch into terminal bronchioles, which end in microscopic air sacs called alveoli.

- Alveoli (singular: alveolus):The alveoli are the functional units of the respiratory system. They have thin, single-layered walls with a vast surface area for efficient gas exchange between air and blood. Alveoli are surrounded by a network of capillaries, allowing oxygen to diffuse from the air into the blood and carbon dioxide to diffuse from the blood into the air.

Gas Exchange: The Vital Dance of Oxygen and Carbon Dioxide

The process of gas exchange occurs in the alveoli, where oxygen and carbon dioxide move between the air and the blood:

- Inspiration (Inhalation): The diaphragm, a dome-shaped muscle below the lungs, contracts and flattens. The chest cavity expands, and the lungs inflate due to the pressure difference. As the lungs expand, air rushes in through the nose or mouth, filling the alveoli. Oxygen from the inhaled air diffuses across the thin alveolar walls and into the blood in the surrounding capillaries.

- Expiration (Exhalation): The diaphragm relaxes, and the chest cavity recoils to its original size. The lungs passively deflate, and air is expelled. During exhalation, carbon dioxide, a waste product of cellular respiration, diffuses from the blood in the capillaries into the alveoli and is then expelled from the body through the respiratory tract.

Regulation of Breathing: Taking Control of Each Breath

Breathing is an involuntary process regulated by the brainstem, specifically the medulla oblongata and the pons. These areas in the brain monitor various factors that influence breathing rate and depth:

- Chemical Regulation: Blood pH and carbon dioxide levels play a crucial role in regulating breathing. When blood CO₂ levels rise or blood pH becomes too acidic (due to CO₂ buildup), chemoreceptors in the medulla oblongata and carotid bodies (located near the carotid arteries) send signals to the brain to increase breathing rate and depth to remove excess CO₂. Conversely, when blood CO₂ levels are low or blood pH becomes too alkaline, breathing slows down.

- Neural Regulation: Stretch receptors in the lungs detect lung inflation and deflation, sending signals to the brainstem to regulate breathing rate and prevent overinflation or collapse of the lungs.

Common Respiratory Disorders: When Breath Becomes a Struggle

Several diseases and conditions can affect the respiratory system, causing difficulty breathing and other symptoms. Here’s an overview of some common respiratory disorders:

- The Common Cold: A viral upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) characterized by symptoms like runny nose, congestion, sore throat, cough, and sneezing. The common cold is usually self-limiting, and symptoms resolve within a week or two.

- Influenza (Flu):

A respiratory illness caused by influenza viruses that can affect the upper and lower respiratory tracts. Symptoms are typically more severe than the common cold, including fever, chills, muscle aches, fatigue, headache, cough, and sore throat. Vaccination is the best way to prevent influenza.

- Sinusitis:

Inflammation of the paranasal sinuses, the air-filled cavities behind the face and forehead. It can be acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term) and can cause facial pain, pressure, congestion, runny nose, and postnasal drip.

- Rhinitis (Hay Fever):

An allergic inflammatory response in the nose triggered by exposure to allergens like pollen, dust mites, or pet dander. Symptoms include runny nose, congestion, sneezing, itchy eyes, and watery eyes.

- Pharyngitis (Sore Throat):

Inflammation of the pharynx, often caused by viral or bacterial infection. Symptoms include sore throat, difficulty swallowing, and sometimes fever.

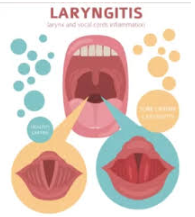

- Laryngitis:

Inflammation of the larynx, often caused by viral infection or vocal strain. Symptoms include hoarseness, loss of voice, cough, and possibly difficulty breathing.

- Asthma:A chronic inflammatory airway disease characterized by recurrent episodes of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough, often triggered by allergens, irritants, or exercise. There is no cure for asthma, but medication and avoidance of triggers can manage symptoms effectively.

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD):A progressive lung disease characterized by airflow obstruction, causing difficulty breathing, cough, and wheezing. COPD is primarily caused by smoking, and there is no cure, but early diagnosis and treatment can slow its progression.

- Pneumonia: An infection of the lung tissue, usually caused by bacteria or viruses. Symptoms include fever, cough (often productive with mucus), shortness of breath, and chest pain. Treatment depends on the type of pneumonia.