MSN: Respiratory System

-

Anatomy and Physiology of the Respiratory System

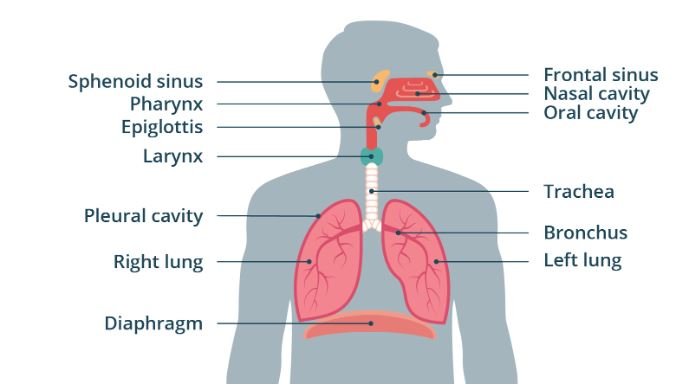

Upper and Lower Respiratory Tracts

The respiratory system is divided into the upper and lower respiratory tracts:

-

Upper Respiratory Tract:

- Nose and Nasal Cavity: The primary entry point for air, where it is filtered, warmed, and humidified. The nasal cavity contains hair-like structures (cilia) and mucus to trap dust, pathogens, and other particles.

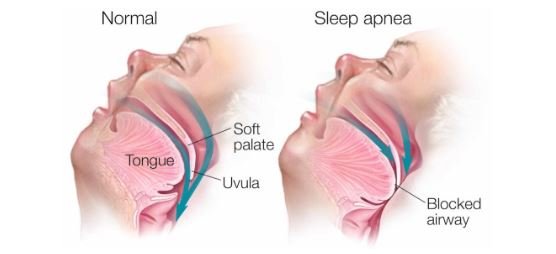

- Pharynx: A muscular tube that connects the nasal cavity to the larynx and esophagus. It serves as a pathway for both air and food.

- Larynx: Also known as the voice box, the larynx is located below the pharynx and houses the vocal cords. It functions as a passageway for air and plays a crucial role in speech production.

-

Lower Respiratory Tract:

- Trachea: Commonly known as the windpipe, the trachea extends from the larynx to the bronchi. It is lined with cilia and mucus to trap and expel foreign particles. The trachea splits into the right and left bronchi, leading to each lung.

- Bronchi and Bronchioles: The bronchi further divide into smaller bronchioles within the lungs. These bronchioles continue to branch into smaller airways, eventually leading to the alveoli. The bronchi and bronchioles are lined with smooth muscle and ciliated epithelium, helping regulate airflow and trap particles.

- Alveoli: Tiny, sac-like structures where gas exchange occurs. Each alveolus is surrounded by a network of capillaries where oxygen from inhaled air diffuses into the blood, and carbon dioxide diffuses from the blood into the alveoli to be exhaled.

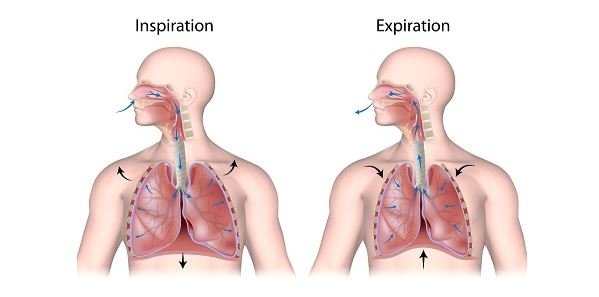

Mechanics of Breathing

Breathing involves the coordinated actions of the respiratory muscles and the lungs to move air in and out of the body. The mechanics of breathing include:

-

Inhalation (Inspiration):

- During inhalation, the diaphragm (a dome-shaped muscle below the lungs) contracts and flattens, increasing the thoracic cavity’s volume. The external intercostal muscles also contract, raising the ribs and further expanding the chest cavity.

- This expansion creates a negative pressure within the thoracic cavity compared to atmospheric pressure, causing air to flow into the lungs.

-

Exhalation (Expiration):

- Exhalation is typically a passive process where the diaphragm and intercostal muscles relax, reducing the thoracic cavity’s volume and increasing pressure inside the lungs.

- The higher pressure within the lungs forces air out through the respiratory tract. In cases of forced exhalation (e.g., during exercise or coughing), the internal intercostal muscles and abdominal muscles contract to expel air more forcefully.

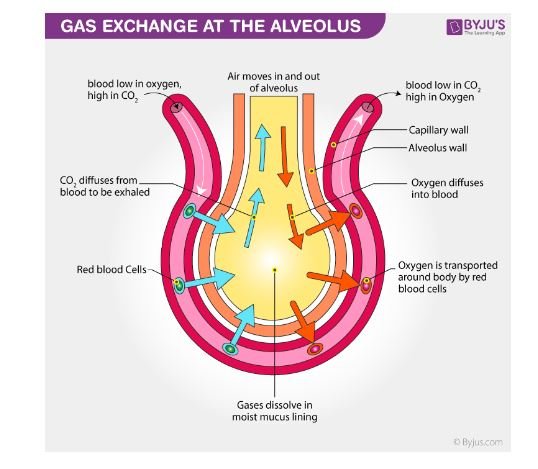

Gas Exchange

Gas exchange occurs in the alveoli, where oxygen from inhaled air diffuses into the blood, and carbon dioxide, a waste product of metabolism, diffuses from the blood into the alveoli to be exhaled. The process is driven by differences in partial pressures:

-

Oxygen Transport:

Oxygen diffuses from the alveoli, where its partial pressure is higher, into the pulmonary capillaries, where its partial pressure is lower. Hemoglobin in red blood cells binds to oxygen, forming oxyhemoglobin, which is transported to tissues.

- Carbon Dioxide Transport: Carbon dioxide, produced by cellular metabolism, diffuses from the tissues into the blood, where it is transported in three forms: dissolved in plasma, bound to hemoglobin, or as bicarbonate ions. In the lungs, carbon dioxide diffuses from the blood into the alveoli and is exhaled.

-

Assessment and Diagnosis

Respiratory Rate and Pattern

Respiratory rate is the number of breaths taken per minute, typically ranging from 12 to 20 breaths per minute in a healthy adult. It is a vital sign that provides important information about a patient’s respiratory and overall health. The respiratory pattern includes the rhythm, depth, and effort of breathing:

-

Tachypnea:

An abnormally high respiratory rate, often seen in conditions like fever, anxiety, or respiratory distress.

- Bradypnea:

An abnormally low respiratory rate, which can occur in conditions like drug overdose or brain injury.

-

Dyspnea:

Difficulty breathing, often associated with conditions like COPD, asthma, or heart failure.

- Apnea:

The absence of breathing, which is life-threatening and requires immediate intervention.

Oxygen Saturation and ABGs

- Oxygen Saturation (SpO2): Measured using pulse oximetry, SpO2 indicates the percentage of hemoglobin saturated with oxygen. Normal SpO2 levels range from 95% to 100%. Levels below 90% indicate hypoxemia, requiring prompt assessment and intervention.

- Arterial Blood Gases (ABGs): ABG analysis provides a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s acid-base balance, oxygenation, and ventilation status. Key parameters include:

- pH: Normal range is 7.35-7.45. A lower pH indicates acidosis, while a higher pH indicates alkalosis.

- PaO2: Partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood, with a normal range of 80-100 mmHg.

- PaCO2: Partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood, with a normal range of 35-45 mmHg. It reflects the effectiveness of ventilation.

- HCO3- (Bicarbonate): Normal range is 22-26 mEq/L, reflecting the metabolic component of acid-base balance.

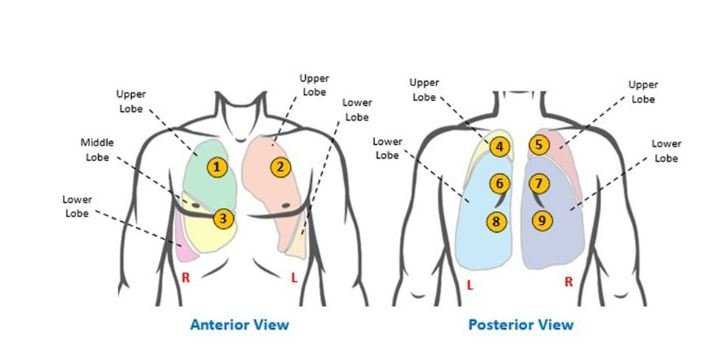

Pulmonary Auscultation

Pulmonary auscultation involves listening to the sounds of breathing using a stethoscope. Different areas of the lungs are auscultated to assess for abnormalities such as:

-

Normal Breath Sounds:

- Vesicular: Soft, low-pitched sounds heard over most of the lung fields.

- Bronchial: Loud, high-pitched sounds heard over the trachea.

- Bronchovesicular: Medium-pitched sounds heard over the main bronchus area and between the scapulae.

-

Adventitious Sounds:

- Crackles (Rales): Discontinuous, popping sounds heard during inspiration, associated with conditions like pneumonia, pulmonary edema, or fibrosis.

- Wheezes: Continuous, high-pitched sounds usually heard during expiration, associated with airway obstruction in conditions like asthma or COPD.

- Rhonchi: Low-pitched, snoring sounds usually associated with secretions in the airways.

- Stridor: A harsh, high-pitched sound usually heard during inspiration, indicating upper airway obstruction.

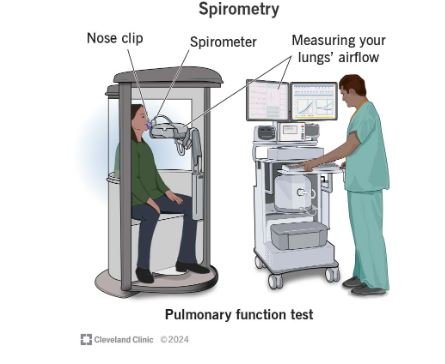

Diagnostic Tests

-

Chest X-ray:

Provides images of the lungs, heart, and bones, helping to diagnose conditions like pneumonia, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, and lung masses.

- Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs): Assess lung function by measuring volumes, capacities, and flow rates. They are essential in diagnosing and monitoring conditions like asthma, COPD, and restrictive lung diseases.

- Spirometry:

Measures the amount and speed of air a person can inhale and exhale, helping to diagnose obstructive and restrictive lung diseases.

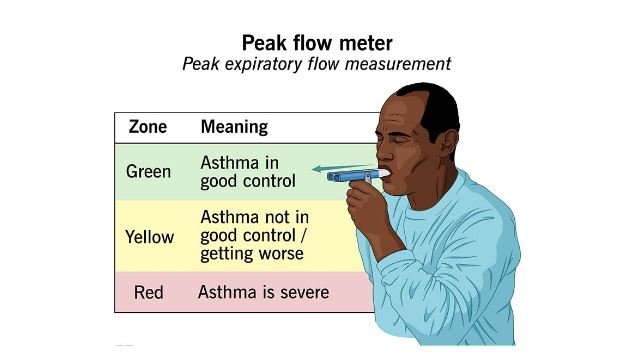

- Peak Flow Measurement:

Assesses the maximum speed of exhalation, useful in monitoring asthma control.

-

Common Respiratory Conditions

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

COPD is a chronic, progressive lung disease characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. It includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis:

-

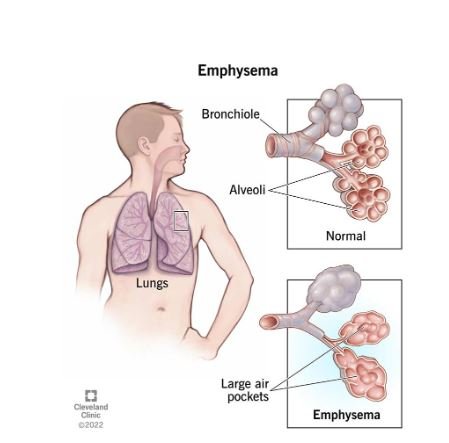

Emphysema:

Destruction of alveoli leads to reduced surface area for gas exchange and loss of lung elasticity, resulting in air trapping and hyperinflation.

-

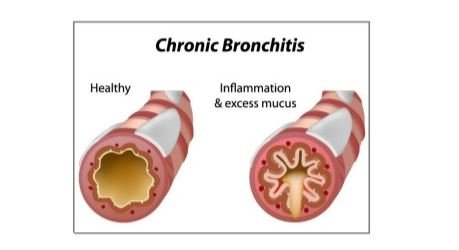

Chronic Bronchitis:

Inflammation of the bronchial tubes with chronic productive cough for at least three months in two consecutive years.

- Symptoms: Include chronic cough, sputum production, dyspnea, and wheezing. Over time, COPD can lead to respiratory failure and right-sided heart failure (cor pulmonale).

- Management: Involves smoking cessation, bronchodilators, corticosteroids, oxygen therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation, and in severe cases, surgical interventions like lung volume reduction surgery or lung transplantation.

Asthma

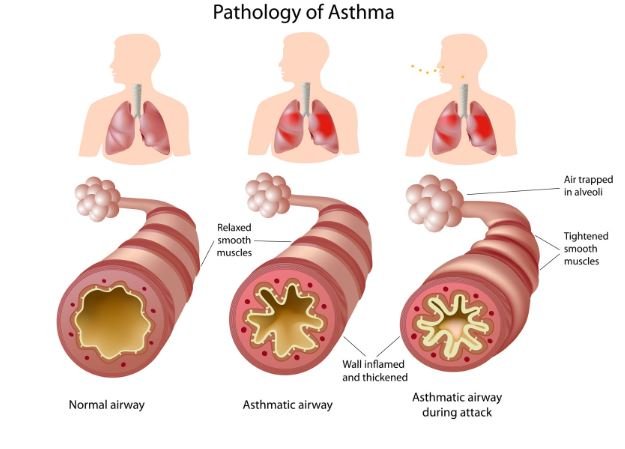

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways, characterized by recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and coughing. These episodes are often triggered by factors such as allergens, cold air, exercise, or respiratory infections:

- Pathophysiology: Inflammation leads to airway hyperresponsiveness, mucus production, and bronchoconstriction, resulting in airway obstruction.

- Management: Involves the use of quick-relief medications (e.g., short-acting beta-agonists) and long-term control medications (e.g., inhaled corticosteroids, long-acting beta-agonists). Patient education on avoiding triggers and proper inhaler technique is crucial.

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an infection of the lung parenchyma that results in inflammation and consolidation of the affected lung tissue:

- Etiology: Can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, or aspiration. Common bacterial causes include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

- Symptoms: Include fever, chills, productive cough, pleuritic chest pain, and dyspnea. Severe cases may lead to hypoxemia and sepsis.

- Diagnosis: Confirmed through clinical assessment, chest X-ray, and sputum culture.

- Management: Depends on the causative agent and may include antibiotics, antiviral agents, oxygen therapy, and supportive care.

Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

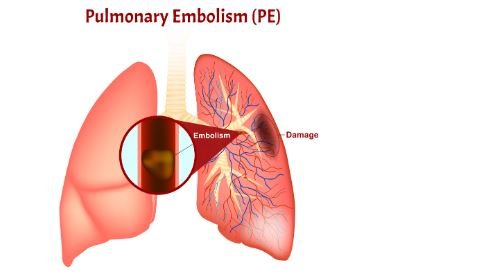

PE is the obstruction of one or more pulmonary arteries by a thrombus, often originating from a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in the lower extremities:

- Pathophysiology: The thrombus travels through the bloodstream, lodges in the pulmonary arteries, and obstructs blood flow, leading to ventilation-perfusion mismatch, hypoxemia, and right ventricular strain.

- Symptoms: Include sudden onset of dyspnea, chest pain, tachypnea, tachycardia, and, in severe cases, syncope or shock.

- Diagnosis: Involves imaging studies such as CT pulmonary angiography, D-dimer testing, and, in some cases, ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan.

- Management: Includes anticoagulation therapy, thrombolytic therapy in severe cases, and, in certain situations, surgical intervention like embolectomy or placement of an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter.

Tuberculosis (TB)

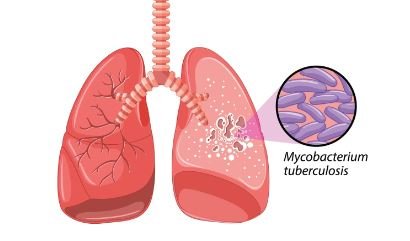

Lung Infected with Tuberclosis (TB)

TB is a contagious bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, primarily affecting the lungs but can also involve other organs:

- Transmission: TB spreads through airborne droplets when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

- Symptoms: Include a persistent cough, hemoptysis, night sweats, weight loss, and fatigue. TB can be latent (asymptomatic) or active.

- Diagnosis: Confirmed through a combination of skin testing (Mantoux test), interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs), chest X-ray, and sputum culture for acid-fast bacilli (AFB).

- Management: Involves a long course of multiple antibiotics (e.g., isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, pyrazinamide) for at least six months. Adherence to the treatment regimen is critical to prevent drug resistance.

-

Treatment and Management

Pharmacological Interventions

-

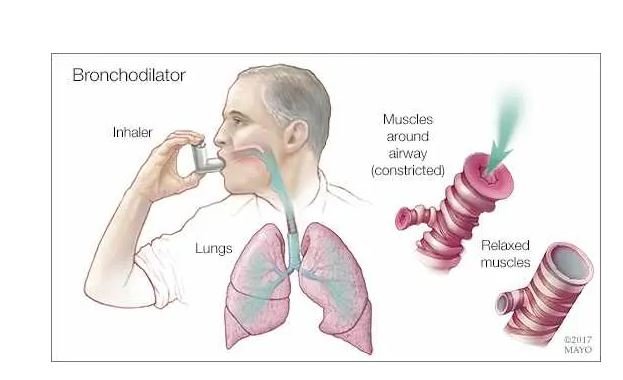

Bronchodilators:

Medications that relax the smooth muscles of the airways, improving airflow. Examples include short-acting beta-agonists (e.g., albuterol), long-acting beta-agonists (e.g., salmeterol), and anticholinergics (e.g., ipratropium).

-

Corticosteroids:

Anti-inflammatory medications that reduce airway inflammation, commonly used in conditions like asthma and COPD. They can be administered orally, intravenously, or via inhalation.

- Antibiotics and Antivirals: Used to treat respiratory infections like pneumonia or exacerbations of chronic conditions. The choice of agent depends on the causative organism and patient-specific factors.

Oxygen Therapy

Oxygen therapy is used to maintain adequate oxygenation in patients with respiratory failure or hypoxemia:

-

Delivery Methods:

Include nasal cannula, simple face mask, non-rebreather mask, and high-flow oxygen systems. In more severe cases, mechanical ventilation may be necessary.

- Monitoring: Oxygen saturation should be regularly monitored to adjust oxygen flow and prevent complications like oxygen toxicity.

Respiratory Therapies

-

Nebulization:

A method of delivering medication in the form of mist inhaled into the lungs. Commonly used for bronchodilators and corticosteroids in asthma or COPD exacerbations.

-

Chest Physiotherapy:

Techniques such as percussion, vibration, and postural drainage help mobilize and clear secretions from the lungs, particularly in patients with conditions like cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis.

Patient Education and Self-Care

Educating patients about their respiratory condition, treatment plan, and self-care is essential for effective management:

- Inhaler Use: Patients should be taught the correct technique for using inhalers to ensure proper medication delivery.

- Smoking Cessation: Smoking is a major risk factor for many respiratory conditions. Providing resources and support for smoking cessation is critical.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Encourage regular exercise, a healthy diet, and avoiding triggers like allergens or air pollutants.

- Symptom Monitoring: Patients should be aware of the signs of worsening symptoms and when to seek medical attention.

-

Emergency Care

Acute Respiratory Distress

Acute respiratory distress is a medical emergency characterized by severe difficulty in breathing. It can result from conditions like ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome), severe asthma, or exacerbation of COPD:

- Initial Management: Includes ensuring a patent airway, providing high-flow oxygen, and closely monitoring the patient’s respiratory status.

- Advanced Interventions: May involve non-invasive ventilation (e.g., CPAP or BiPAP) or mechanical ventilation in cases of respiratory failure.

Airway Management

Airway management is critical in situations where the patient’s airway is compromised, such as in trauma, anaphylaxis, or severe respiratory distress:

- Basic Airway Maneuvers: Include head tilt-chin lift or jaw thrust to open the airway.

- Advanced Airway Techniques: May involve intubation, use of supraglottic airway devices, or in emergency situations, cricothyrotomy.

Crisis Management

-

Severe Asthma Attack:

Also known as status asthmaticus, it is a life-threatening condition that does not respond to standard treatments. Management includes aggressive bronchodilation, systemic corticosteroids, magnesium sulfate, and possibly mechanical ventilation.

-

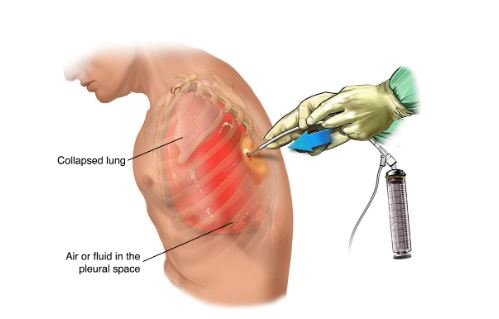

Pneumothorax:

A pneumothorax is the presence of air in the pleural space, leading to lung collapse. It can be spontaneous or traumatic. Treatment may involve needle decompression or chest tube insertion to re-expand the lung.